Sam Kahn in The New Atlantis:

In 1844, a Nashville gentleman named Return Jonathan Meigs was placidly reading Francis Bacon in the evening when he suddenly slammed the book shut and, in the presence of his startled fourteen-year-old son, declared, “This man Bacon wrote the works of Shakespeare.”

In 1844, a Nashville gentleman named Return Jonathan Meigs was placidly reading Francis Bacon in the evening when he suddenly slammed the book shut and, in the presence of his startled fourteen-year-old son, declared, “This man Bacon wrote the works of Shakespeare.”

A few years later, the American writer Joseph C. Hart, in his book The Romance of Yachting and à propos of absolutely nothing — amidst ruminations on a voyage to Spain, and after a section about bullfighting — announced his belief that Shakespeare was just a copyist in a theater, a name assigned to the plays almost at random. “The enquiry will be, who were the able literary men who wrote the dramas imputed to him?” Hart wrote.

What’s curious about the idea that Shakespeare didn’t write his plays is that, for over two hundred years after his death, there was barely a whiff of rumor that anyone other than Shakespeare had written them, and then, around 1850, there was something in the water, and several people, completely independently, came to the same novel conclusion: Francis Bacon, the statesman, man of letters, and founder of modern science, was the literary genius behind Hamlet and King Lear, The Tempest and Henry V, and all the rest.

More here.

For years I’ve interacted with people who seem to agree with me on the issues—the government should fund technology policy, nuclear energy is good, not bad, economic growth can drive positive-sum improvements for humans and nature, environmental activists are kind of full of shit—but who, when pressed, stop short of fully endorsing ecomodernism as a philosophy or a project. And while we at the Breakthrough Institute have done our best to set up ecomodernism as a “big tent,” inclusive of all sorts of ideological backgrounds and merely “ecomodern-ish” folks, many of these people have left me puzzled. Even discounting the fact that most people will not take as enthusiastically to ecomodernism as I do, it just seems obvious to me that many more of these people should get on board than have done so to date.

For years I’ve interacted with people who seem to agree with me on the issues—the government should fund technology policy, nuclear energy is good, not bad, economic growth can drive positive-sum improvements for humans and nature, environmental activists are kind of full of shit—but who, when pressed, stop short of fully endorsing ecomodernism as a philosophy or a project. And while we at the Breakthrough Institute have done our best to set up ecomodernism as a “big tent,” inclusive of all sorts of ideological backgrounds and merely “ecomodern-ish” folks, many of these people have left me puzzled. Even discounting the fact that most people will not take as enthusiastically to ecomodernism as I do, it just seems obvious to me that many more of these people should get on board than have done so to date. American culture feels dangerously stuck and stilted these days. Many of our best and brightest look for all the world as if they were standing at the tail end of something, equipped with resources fit for a bygone reality, at loose ends in this one. In a perfect bit of performance poetry—who says mass societies can’t be poetical?—we keep cycling through the halls of leadership a cast of tottering, familiar, reassuring grandparents, who spend their tenures insider-trading and murmuring hits from the old boomer songbook, desperately hoping that no cameras are running when they nod off, just a skosh, into their salad, or tip over their mountain bikes, ever so gingerly. Our president turns eighty in November, and he is vowing to run again. We have no new ideas for America. The best in our culture lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity (approximately). A soft apocalypticism seems to be in the water.

American culture feels dangerously stuck and stilted these days. Many of our best and brightest look for all the world as if they were standing at the tail end of something, equipped with resources fit for a bygone reality, at loose ends in this one. In a perfect bit of performance poetry—who says mass societies can’t be poetical?—we keep cycling through the halls of leadership a cast of tottering, familiar, reassuring grandparents, who spend their tenures insider-trading and murmuring hits from the old boomer songbook, desperately hoping that no cameras are running when they nod off, just a skosh, into their salad, or tip over their mountain bikes, ever so gingerly. Our president turns eighty in November, and he is vowing to run again. We have no new ideas for America. The best in our culture lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity (approximately). A soft apocalypticism seems to be in the water. As a grad student in cell biology,

As a grad student in cell biology,  What exactly is an “oral history,” and why would we need one? Most history begins and ends with personal witness, and even written documents, after all, were very often once spoken memories, with many of the best histories depending on recollected conversation, from Boswell’s life of Dr. Johnson to the court memoirs of Saint-Simon. Yet the term has become so much a part of our book culture that it tells us to expect something very specific: a heavily edited chain of first-person recollections, broken into distinct related bits, about a place or a system or an event. Although the contemporary version has roots in the oral histories compiled by the W.P.A. in the nineteen-thirties, it seems to derive, in form, from documentary films of the sixties like those of D. A. Pennebaker and Richard Leacock, in which testimony is offered in sequential counterpoint, without explicit commentary.

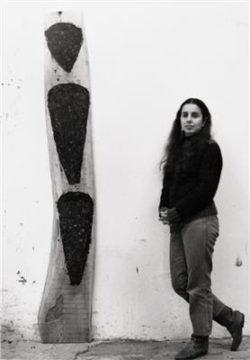

What exactly is an “oral history,” and why would we need one? Most history begins and ends with personal witness, and even written documents, after all, were very often once spoken memories, with many of the best histories depending on recollected conversation, from Boswell’s life of Dr. Johnson to the court memoirs of Saint-Simon. Yet the term has become so much a part of our book culture that it tells us to expect something very specific: a heavily edited chain of first-person recollections, broken into distinct related bits, about a place or a system or an event. Although the contemporary version has roots in the oral histories compiled by the W.P.A. in the nineteen-thirties, it seems to derive, in form, from documentary films of the sixties like those of D. A. Pennebaker and Richard Leacock, in which testimony is offered in sequential counterpoint, without explicit commentary. HERE IS WHAT WE KNOW: In 1979, Ana Mendieta, a young, up-and-coming artist fresh off a solo show at the feminist co-op A.I.R. Gallery, met the older, more famous Carl Andre, a so-called founding father of Minimalism. The artists embarked on a romantic and, by several accounts, tempestuous relationship. In 1985, Mendieta died after falling from the window of Andre’s thirty-fourth-floor apartment in New York’s Greenwich Village. He was tried, and acquitted, for her murder. Now eighty-seven, Andre—still living, somewhat astoundingly, in that same apartment—has carried on with his career, exhibiting regularly in museums and galleries throughout the world. Yet not everyone is convinced of his innocence, as we hear in Death of an Artist, a six-episode podcast from writer-curator Helen Molesworth. In addition to offering a précis on the defects of the US justice system, the series reframes abiding questions about art through the lens of Mendieta’s case: Are artists’ lives—and deaths—relevant when discussing their work? What about when we suspect that they have committed a terrible crime? Who benefits from silence, and from speaking up?

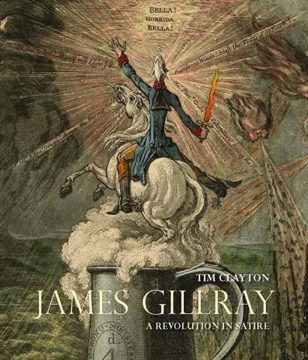

HERE IS WHAT WE KNOW: In 1979, Ana Mendieta, a young, up-and-coming artist fresh off a solo show at the feminist co-op A.I.R. Gallery, met the older, more famous Carl Andre, a so-called founding father of Minimalism. The artists embarked on a romantic and, by several accounts, tempestuous relationship. In 1985, Mendieta died after falling from the window of Andre’s thirty-fourth-floor apartment in New York’s Greenwich Village. He was tried, and acquitted, for her murder. Now eighty-seven, Andre—still living, somewhat astoundingly, in that same apartment—has carried on with his career, exhibiting regularly in museums and galleries throughout the world. Yet not everyone is convinced of his innocence, as we hear in Death of an Artist, a six-episode podcast from writer-curator Helen Molesworth. In addition to offering a précis on the defects of the US justice system, the series reframes abiding questions about art through the lens of Mendieta’s case: Are artists’ lives—and deaths—relevant when discussing their work? What about when we suspect that they have committed a terrible crime? Who benefits from silence, and from speaking up? Children do not tend to feature prominently in the satirical works of the ‘Prince of Caricatura’, James Gillray. As someone professionally committed to excoriating the politicians and celebrities of his day, he was paid to train his eye on the grown-ups. One exception to this rule comes in A March to the Bank, a vast, elaborate print of 1787. It was published in the wake of the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots in London and reflects the city’s outrage at the subsequent military crackdown on public disorder. Gillray blends straight portraiture with lurid exaggeration in his etching: an absurdly dandified, impossibly skinny officer goosesteps over a mob of Londoners, who lie crushed and abandoned in various states of disarray. At the centre of the picture, with the officer’s foot daintily poised on her midriff, lies the grotesque, ungainly figure of a fishwife, still grasping a basket of eels, her hefty legs splayed wide open. A fragment of cloth barely covers her genitals. Next to her lies a baby boy, perhaps her son, who is naked from the waist down and spread-eagled on the edge of the pavement. An impassive-looking soldier has placed the tip of his boot squarely on the child’s face.

Children do not tend to feature prominently in the satirical works of the ‘Prince of Caricatura’, James Gillray. As someone professionally committed to excoriating the politicians and celebrities of his day, he was paid to train his eye on the grown-ups. One exception to this rule comes in A March to the Bank, a vast, elaborate print of 1787. It was published in the wake of the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots in London and reflects the city’s outrage at the subsequent military crackdown on public disorder. Gillray blends straight portraiture with lurid exaggeration in his etching: an absurdly dandified, impossibly skinny officer goosesteps over a mob of Londoners, who lie crushed and abandoned in various states of disarray. At the centre of the picture, with the officer’s foot daintily poised on her midriff, lies the grotesque, ungainly figure of a fishwife, still grasping a basket of eels, her hefty legs splayed wide open. A fragment of cloth barely covers her genitals. Next to her lies a baby boy, perhaps her son, who is naked from the waist down and spread-eagled on the edge of the pavement. An impassive-looking soldier has placed the tip of his boot squarely on the child’s face. Orli Snir, a biologist at the Rockefeller University in New York, couldn’t keep her ants alive. She had plucked pupae from a colony of clonal raider ants, where the sesame seed-size offspring that looked like puffed rice cereal were being fussed over by both younger larvae and older adult ants. Then she had isolated each pupa into a tiny, dry test tube. And every time, they drowned. More specifically, each pupa was leaking so much watery, golden-tinted fluid it was struggling to breathe. But they lived when Dr. Snir whisked the fluid away with a capillary tube. Her humble observation led down a strange path of experiments toward a bizarre but inescapable conclusion: This mysterious ant goo functions a lot like milk.

Orli Snir, a biologist at the Rockefeller University in New York, couldn’t keep her ants alive. She had plucked pupae from a colony of clonal raider ants, where the sesame seed-size offspring that looked like puffed rice cereal were being fussed over by both younger larvae and older adult ants. Then she had isolated each pupa into a tiny, dry test tube. And every time, they drowned. More specifically, each pupa was leaking so much watery, golden-tinted fluid it was struggling to breathe. But they lived when Dr. Snir whisked the fluid away with a capillary tube. Her humble observation led down a strange path of experiments toward a bizarre but inescapable conclusion: This mysterious ant goo functions a lot like milk. For over a decade, scientists have been grappling with the alarming realization that many published findings — in fields ranging from psychology to cancer biology — may actually be wrong. Or at least, we don’t know if they’re right, because they just don’t hold up when other scientists repeat the same experiments, a process known as replication. In a 2015

For over a decade, scientists have been grappling with the alarming realization that many published findings — in fields ranging from psychology to cancer biology — may actually be wrong. Or at least, we don’t know if they’re right, because they just don’t hold up when other scientists repeat the same experiments, a process known as replication. In a 2015  In 1952, the Sight and Sound team had the novel idea of asking critics to name the greatest films of all time. The tradition became decennial, increasing in size and prestige as the decades passed.

In 1952, the Sight and Sound team had the novel idea of asking critics to name the greatest films of all time. The tradition became decennial, increasing in size and prestige as the decades passed. The magma that comes out of Mauna Loa comes from a series of magma chambers found between about 1 and 25 miles (2 and 40 km) below the surface. These magma chambers are only temporary storage places with magma and gases, and are not where the magma originally came from.

The magma that comes out of Mauna Loa comes from a series of magma chambers found between about 1 and 25 miles (2 and 40 km) below the surface. These magma chambers are only temporary storage places with magma and gases, and are not where the magma originally came from. In this provocative book, Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow argue that, today, every working artist is a bond servant. Culture is the bait adverts are sold around, but artists see almost nothing of the billions Google, Facebook and Apple and make off their backs. We have entered a new era of “chokepoint capitalism”, in which businesses snake their way between audiences and creatives to harvest money that should rightfully belong to the artist.

In this provocative book, Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow argue that, today, every working artist is a bond servant. Culture is the bait adverts are sold around, but artists see almost nothing of the billions Google, Facebook and Apple and make off their backs. We have entered a new era of “chokepoint capitalism”, in which businesses snake their way between audiences and creatives to harvest money that should rightfully belong to the artist. most gut-wrenching exploration of what it feels like to be cancelled is in a novel written long before that term had become a weapon in the culture wars. In Philip Roth’s The Human Stain, published in 2000, Coleman Silk, a professor and former dean at the fictional Athena College, is teaching a seminar with 14 students.

most gut-wrenching exploration of what it feels like to be cancelled is in a novel written long before that term had become a weapon in the culture wars. In Philip Roth’s The Human Stain, published in 2000, Coleman Silk, a professor and former dean at the fictional Athena College, is teaching a seminar with 14 students. A year ago Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies were selling at record prices, with a combined market value of around

A year ago Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies were selling at record prices, with a combined market value of around  When Aristotle sniffed an apple, he smelled it. When he bit into the apple and the flesh touched his tongue, he tasted it. But he overlooked something that caused 2,000 years of confusion.

When Aristotle sniffed an apple, he smelled it. When he bit into the apple and the flesh touched his tongue, he tasted it. But he overlooked something that caused 2,000 years of confusion.