Erik Hoel in The Intrinsic Perspective:

Despite being the culmination of a century-long dream, no better word describes the much-discussed output of OpenAI’s ChatGPT than the colloquial “mid.”

Despite being the culmination of a century-long dream, no better word describes the much-discussed output of OpenAI’s ChatGPT than the colloquial “mid.”

I understand that this may be seen as downplaying its achievement. As those who’ve been paying attention to this space can attest, ChatGPT is by far the most impressive AI the public has had access to. It can basically pass the Turing test—conversationally, it acts much like a human. These new changes are from it having been given a lot of feedback and tutoring by humans themselves. ChatGPT was created by taking the original GPT-3 model and fine-tuning it on human ratings of its responses, e.g., OpenAI had humans interact with GPT-3, its base model, then rate how satisfied they were with the answer. ChatGPT’s connections were then shifted to give more weight to the ones that were important for producing human-pleasing answers.

Therefore, before we can discuss why ChatGPT is actually unimpressive, first we must admit that ChatGPT is impressive.

More here.

Our goal isn’t to try convince you to take one side over the other in a debate about optimism and pessimism – the world is far too muddled for that. Instead, it’s to remind you that away from the headlines, millions of people from every corner of the planet did their best to solve the problems that could be solved, and stayed open-eyed and open-hearted even in the most difficult of circumstances.

Our goal isn’t to try convince you to take one side over the other in a debate about optimism and pessimism – the world is far too muddled for that. Instead, it’s to remind you that away from the headlines, millions of people from every corner of the planet did their best to solve the problems that could be solved, and stayed open-eyed and open-hearted even in the most difficult of circumstances. IT’S A FUNNY THING TO LEARN

IT’S A FUNNY THING TO LEARN Before we started filming, I asked someone from the production team when I would meet makeup, hair, and wardrobe, and was told that I would be doing my own. I was also informed that Godard would be stopping by my room to choose Cordelia’s costumes from the clothes I had brought with me. It was the first I’d heard of this, and I suddenly wished I had been more selective in my packing. I went back to my room, picked out a nice sweater and skirt, tied a scarf in my hair, and carefully applied my makeup. Then I wrote postcards while I waited for Godard, the contents of my suitcase neatly arranged on the bed. When I greeted him and an assistant at the door, he took one look at my face and exclaimed, “No, no, no! Too much makeup! Take it off. If you must, just a little mascara, that’s all.” The “a” in “all” was pronounced as an “o,” articulated in the exact same way he later asked me to pronounce Cordelia’s answer to her father’s question about what she will say to prove her love for him. “Not no‑thing.” no thing. He split the word in two, and I could tell that this distinction was important to him, without really understanding why.

Before we started filming, I asked someone from the production team when I would meet makeup, hair, and wardrobe, and was told that I would be doing my own. I was also informed that Godard would be stopping by my room to choose Cordelia’s costumes from the clothes I had brought with me. It was the first I’d heard of this, and I suddenly wished I had been more selective in my packing. I went back to my room, picked out a nice sweater and skirt, tied a scarf in my hair, and carefully applied my makeup. Then I wrote postcards while I waited for Godard, the contents of my suitcase neatly arranged on the bed. When I greeted him and an assistant at the door, he took one look at my face and exclaimed, “No, no, no! Too much makeup! Take it off. If you must, just a little mascara, that’s all.” The “a” in “all” was pronounced as an “o,” articulated in the exact same way he later asked me to pronounce Cordelia’s answer to her father’s question about what she will say to prove her love for him. “Not no‑thing.” no thing. He split the word in two, and I could tell that this distinction was important to him, without really understanding why. Anton Chekhov’s biography in 1886-1887 is captured almost completely in the writing that he was doing. Reading the stories, we are as close as we can be to being in his company.

Anton Chekhov’s biography in 1886-1887 is captured almost completely in the writing that he was doing. Reading the stories, we are as close as we can be to being in his company. Motivation to exercise may come from the gut in addition to the brain. A study in mice finds that

Motivation to exercise may come from the gut in addition to the brain. A study in mice finds that  A few years ago I was invited to an off-the-record meeting with senior executives at a major social media company. The topic was free speech. I’d just written a piece for the New York Times called “

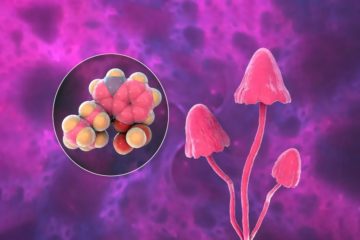

A few years ago I was invited to an off-the-record meeting with senior executives at a major social media company. The topic was free speech. I’d just written a piece for the New York Times called “ It seems as though “magic” mushrooms containing the psychedelic drug psilocybin are suddenly in vogue, judging by the sudden pop up of

It seems as though “magic” mushrooms containing the psychedelic drug psilocybin are suddenly in vogue, judging by the sudden pop up of  Last year, the Survey Center on American Life published a

Last year, the Survey Center on American Life published a  In the early ’90s, the FBI had learned of a Vietnamese-Chinese heroin organization that was closely aligned with Vietnamese street gangs throughout the United States. Their connections were wide-ranging, and they were loosely affiliated with the Triads (including Frank Ma, one of the last Chinese “godfathers” in New York), as well as with several other high-echelon Asian crime bosses in various American cities. But this heroin organization operated differently from the Asian gangs of previous generations.

In the early ’90s, the FBI had learned of a Vietnamese-Chinese heroin organization that was closely aligned with Vietnamese street gangs throughout the United States. Their connections were wide-ranging, and they were loosely affiliated with the Triads (including Frank Ma, one of the last Chinese “godfathers” in New York), as well as with several other high-echelon Asian crime bosses in various American cities. But this heroin organization operated differently from the Asian gangs of previous generations. Jünger’s politics were complicated, if not incoherent. A decorated veteran of the First World War (he made his literary debut with a bellicose, best-selling diary from the trenches, Storm of Steel) who was praised by Hitler but who refused to join the Nazi Party; a self-taught conservative intellectual (Jünger never completed university) who won the admiration of Marxist writers like Bertolt Brecht; an incurable elitist sympathetic to communist centralization (he opposed liberalism above all)—the Weimar-era Jünger projected an aloof, aestheticizing, and ultimately paradoxical strain of fascism. Kracauer captured what feels most damning about Jünger’s political thinking during this time in a review of his controversial treatise The Worker (1932) for the Frankfurter Zeitung, in which he accused Jünger of having “metaphysicized” (metaphysiziert) politics: What about real, tangible action in our own historical moment? Metaphysics is an escape.

Jünger’s politics were complicated, if not incoherent. A decorated veteran of the First World War (he made his literary debut with a bellicose, best-selling diary from the trenches, Storm of Steel) who was praised by Hitler but who refused to join the Nazi Party; a self-taught conservative intellectual (Jünger never completed university) who won the admiration of Marxist writers like Bertolt Brecht; an incurable elitist sympathetic to communist centralization (he opposed liberalism above all)—the Weimar-era Jünger projected an aloof, aestheticizing, and ultimately paradoxical strain of fascism. Kracauer captured what feels most damning about Jünger’s political thinking during this time in a review of his controversial treatise The Worker (1932) for the Frankfurter Zeitung, in which he accused Jünger of having “metaphysicized” (metaphysiziert) politics: What about real, tangible action in our own historical moment? Metaphysics is an escape. This year marks the centenary of modernism’s annus mirabilis. For many, that means T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and James Joyce’s Ulysses—both first published in book form in 1922—perhaps along with the first English language translation of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. These books are in different genres and disciplines—poetry, fiction, philosophy—but all of them wed experimental literary aesthetics with highly abstract intellectual projects. All invoke myths to represent immense aesthetic and intellectual challenges: each tells of an arduous journey, that could, if successful, be redemptive, even transformative. Each text has its hero, but in each case the hero is also—or really—you. You, the reader, are challenged to find your way through these depths and heights and broad, rough seas. The journey is perilous, filled with traps as well as marvels. Should you succeed, your home may look different by the end; you will be changed too.

This year marks the centenary of modernism’s annus mirabilis. For many, that means T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and James Joyce’s Ulysses—both first published in book form in 1922—perhaps along with the first English language translation of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. These books are in different genres and disciplines—poetry, fiction, philosophy—but all of them wed experimental literary aesthetics with highly abstract intellectual projects. All invoke myths to represent immense aesthetic and intellectual challenges: each tells of an arduous journey, that could, if successful, be redemptive, even transformative. Each text has its hero, but in each case the hero is also—or really—you. You, the reader, are challenged to find your way through these depths and heights and broad, rough seas. The journey is perilous, filled with traps as well as marvels. Should you succeed, your home may look different by the end; you will be changed too. Life is rich with moments of uncertainty, where we’re not exactly sure what’s going to happen next. We often find ourselves in situations where we have to choose between different kinds of uncertainty; maybe one option is very likely to have a “pretty good” outcome, while another has some probability for “great” and some for “truly awful.” In such circumstances, what’s the rational way to choose? Is it rational to go to great lengths to avoid choices where the worst outcome is very bad? Lara Buchak argues that it is, thereby expanding and generalizing the usual rules of rational choice in conditions of risk.

Life is rich with moments of uncertainty, where we’re not exactly sure what’s going to happen next. We often find ourselves in situations where we have to choose between different kinds of uncertainty; maybe one option is very likely to have a “pretty good” outcome, while another has some probability for “great” and some for “truly awful.” In such circumstances, what’s the rational way to choose? Is it rational to go to great lengths to avoid choices where the worst outcome is very bad? Lara Buchak argues that it is, thereby expanding and generalizing the usual rules of rational choice in conditions of risk.