Category: Recommended Reading

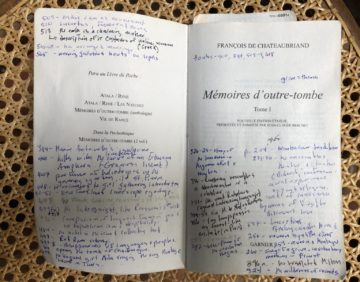

Only Style Survives: On Chateaubriand

Lisa Robertson at The Paris Review:

Chateaubriand says that the pleasures of youth revisited in memory are ruins seen by torchlight. I don’t know whether I’m the ruin or the torch.

Chateaubriand says that the pleasures of youth revisited in memory are ruins seen by torchlight. I don’t know whether I’m the ruin or the torch.

Montaigne was dead at fifty-nine—kidneys; Baudelaire at forty-six—syphilis, probably. Rousseau died at sixty-six of causes unconnected to his lifelong urethral malformation, described so exhaustively and enticingly by Starobinski; Lord Byron died of fever at the age of thirty-six in the Greek War of Independence in 1824, the year of Baudelaire’s birth. After a final visit to his mistress, Madame Récamier, he by then blind and she paralytic, Chateaubriand died at the age of seventy-nine, in 1848, the year of the third revolution and its failure and of Baudelaire’s grand political disillusionment. The attribution of causation to human behavior is generally a work of fantasy. Birds will speak the last human words, Chateaubriand says. Each one of us is the last witness of something—some custom, habit, way of speaking, economy, some lapsed mode of life. He says only style survives.

more here.

Tuesday Poem

Prayer

I invite you back

…………….. dear wildness dear

…………………………………….. unfathomable formless

…………………….. universe of expansion

you alaap and scat

……………………. of tongue and throat

come seed me

……………….. my ground I’ve prepared

……………………………… ready for divinity

make day of my night

revolution in my field

come burn

……………. fallow grass

…………………………. and mustard alike

and I will string your each flame

……………………………………………. about my neck

until you flare into me

…………………. and I like you burn

……………………………………………. beyond recognition

by Rajiv Mohabir

from Split This Rock

Tough Guy: The Life of Norman Mailer – a literary sucker punch

Peter Conrad in The Guardian:

Norman Mailer – when not boozily brawling, dosing himself with hallucinogenic drugs and serially fornicating – was a man with a sacred mission. He regarded himself as a prophet, bringing bad news to a society that had settled into consumerist complacency during the 1950s. Americans believe that they live in God’s own country; Mailer alerted them to “the possible existence of Satan”, who might be residing next door and quietly assembling a private arsenal for use on Judgment Day. Although Mailer looked up at the sky with “religious awe”, what he saw there was a mushroom-shaped cloud that he called “the last deity”. Humanity, he declared, was reeling towards self-destruction. Now that his centenary has arrived (he was born 31 January 1923), I dare anyone – and that includes Richard Bradford, the author of this sensationalised canter through his life – to say that he was wrong.

Norman Mailer – when not boozily brawling, dosing himself with hallucinogenic drugs and serially fornicating – was a man with a sacred mission. He regarded himself as a prophet, bringing bad news to a society that had settled into consumerist complacency during the 1950s. Americans believe that they live in God’s own country; Mailer alerted them to “the possible existence of Satan”, who might be residing next door and quietly assembling a private arsenal for use on Judgment Day. Although Mailer looked up at the sky with “religious awe”, what he saw there was a mushroom-shaped cloud that he called “the last deity”. Humanity, he declared, was reeling towards self-destruction. Now that his centenary has arrived (he was born 31 January 1923), I dare anyone – and that includes Richard Bradford, the author of this sensationalised canter through his life – to say that he was wrong.

True, Mailer was an obnoxious loudmouth. In episodes that Bradford documents with slavering relish, he conducted literary disputes by butting his colleagues: “Once again words fail you,” drawled the coolly disdainful Gore Vidal after one such attack.

Domestically, Mailer was a wife-beater and almost a murderer: taunted as a “faggot” by the second of his six spouses, he stabbed her with a penknife at a drunken party, just missing her heart. After an early infatuation with President Kennedy, whose fatal ride through Dallas in an open car he applauded as a moment of existentialist bravado, his politics lurched towards fascism. He commended Hitler for providing Germans with an outlet for their “energies”, although – as a man who bragged about his own bulbous, fizzily fertile “cojones” and the indefatigable piston of his penis – he pitied the Führer for possessing only one testicle and having to rely on masturbation.

More here.

Colonoscopies save lives. Why did a trial suggest they might not?

Emily Sohn in Nature:

It was an uncomfortable moment for people who perform colonoscopies. In October, a massive randomized clinical trial in Europe presented its initial results1, which suggested that, as a screening tool, colonoscopies don’t save as many lives as expected. Researchers were perplexed because the procedure had long been considered a true success story in cancer screening. But after the study results were compared with data from other trials, colonoscopy to be seemed less effective than simpler screening methods that assess only part of the colon. Jason Dominitz, a physician at the Veterans Health Administration in Seattle, Washington, says it was like suggesting that mammography on only one breast was better than scanning both. It didn’t make sense.

It was an uncomfortable moment for people who perform colonoscopies. In October, a massive randomized clinical trial in Europe presented its initial results1, which suggested that, as a screening tool, colonoscopies don’t save as many lives as expected. Researchers were perplexed because the procedure had long been considered a true success story in cancer screening. But after the study results were compared with data from other trials, colonoscopy to be seemed less effective than simpler screening methods that assess only part of the colon. Jason Dominitz, a physician at the Veterans Health Administration in Seattle, Washington, says it was like suggesting that mammography on only one breast was better than scanning both. It didn’t make sense.

A media frenzy followed, and headlines were blunt, declaring that colonoscopies might not be effective or prevent deaths at all. But when Dominitz dug deeper, the trial results reflected where and how the study was conducted and the complexity of the questions it was trying to answer. “It is really important to not just read the headline,” says Dominitz, who is also director of the colorectal-cancer screening programme run by the US Department of Veteran Affairs.

More here.

Sunday, January 8, 2023

In Honor of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Who Gave Us Flow

Jeannette Cooperman in The Common Reader:

My exultant “Ha!” woke the library. I had just read Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s definition of “flow”—that magical feeling of getting so caught up in what you are doing that you lose track of where you are, what time it is, who might want something of you. I knew that feeling, and I craved it. Freed from space and time, oblivious to chores and deadlines, I could think and breathe and imagine. These bursts of oblivion drove everybody around me crazy, of course. I re-entered the world in a daze and had to scramble back into task-mind. But I came back refreshed and happy.

My exultant “Ha!” woke the library. I had just read Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s definition of “flow”—that magical feeling of getting so caught up in what you are doing that you lose track of where you are, what time it is, who might want something of you. I knew that feeling, and I craved it. Freed from space and time, oblivious to chores and deadlines, I could think and breathe and imagine. These bursts of oblivion drove everybody around me crazy, of course. I re-entered the world in a daze and had to scramble back into task-mind. But I came back refreshed and happy.

Eager to learn how to summon the state at will, I read Csikszentmihalyi’s criteria. First, the challenge must be proportional to your skill. Too difficult, and you will be anxious; too easy, and you will be bored. Next, you must be completely involved in the task at hand, focused, and concentrating (an ability we are all fast losing). Your motivation must be intrinsic, rooted in the task itself. You must have a clear sense of what you are doing and how well you are doing it.

All this struck me with such force that I memorized both the spelling and pronunciation (chick-SENT-me-high) of the man’s name, tossing it into conversations whenever possible.

More here.

A new look at the case of the first gene-edited babies

G. Owen Schaefer in The Conversation:

In the four years since an experiment by disgraced scientist He Jiankui resulted in the birth of the first babies with edited genes, numerous articles, books and international commissions have reflected on whether and how heritable genome editing – that is, modifying genes that will be passed on to the next generation – should proceed. They’ve reinforced an international consensus that it’s premature to proceed with heritable genome editing. Yet, concern remains that some individuals might buck that consensus and recklessly forge ahead – just as He Jiankui did.

In the four years since an experiment by disgraced scientist He Jiankui resulted in the birth of the first babies with edited genes, numerous articles, books and international commissions have reflected on whether and how heritable genome editing – that is, modifying genes that will be passed on to the next generation – should proceed. They’ve reinforced an international consensus that it’s premature to proceed with heritable genome editing. Yet, concern remains that some individuals might buck that consensus and recklessly forge ahead – just as He Jiankui did.

Some observers – myself included – have characterized He as a rogue. However, the new documentary “Make People Better,” directed by filmmaker Cody Sheehy, leans toward a different narrative.

More here.

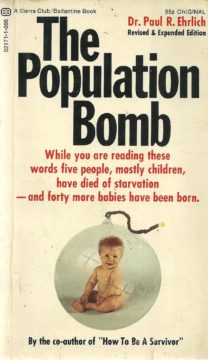

Why Paul Ehrlich got everything wrong

Noah Smith in Noahpinion:

Biologist Paul Ehrlich is one of the most discredited popular intellectuals in America. He’s so discredited that his Wikipedia page starts the second paragraph with “Ehrlich became well known for the discredited 1968 book The Population Bomb”. In that book he predicted that hundreds of millions of people would starve to death in the decade to come; when no such thing happened (in the 70s or ever so far), Ehrlich’s name became sort of a household joke among the news-reading set.

Biologist Paul Ehrlich is one of the most discredited popular intellectuals in America. He’s so discredited that his Wikipedia page starts the second paragraph with “Ehrlich became well known for the discredited 1968 book The Population Bomb”. In that book he predicted that hundreds of millions of people would starve to death in the decade to come; when no such thing happened (in the 70s or ever so far), Ehrlich’s name became sort of a household joke among the news-reading set.

And yet despite all this, in the year 2022, 60 Minutes still had Ehrlich on to offer his thoughts on wildlife loss…

More here.

Why the Godfather of Human Rights Is Not Welcome at Harvard

Michael Massing in The Nation:

Soon after Kenneth Roth announced in April that he planned to step down as the head of Human Rights Watch, he was contacted by Sushma Raman, the executive director of the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. Raman asked Roth if he would be interested in joining the center as a senior fellow. It seemed like a natural fit. In Roth’s nearly 30 years as the executive director of HRW, its budget had grown from $7 million to nearly $100 million, and its staff had gone from 60 to 550 people monitoring more than 100 countries. The “godfather” of human rights, The New York Times called him in a long, admiring overview of his career, noting that Roth “has been an unrelenting irritant to authoritarian governments, exposing human rights abuses with documented research reports that have become the group’s specialty.” HRW played a prominent role in establishing the International Criminal Court, and it helped secure the convictions of Charles Taylor of Liberia, Alberto Fujimori of Peru, and (in a tribunal for the former Yugoslavia) the Bosnian Serb leaders Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladic.

Soon after Kenneth Roth announced in April that he planned to step down as the head of Human Rights Watch, he was contacted by Sushma Raman, the executive director of the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. Raman asked Roth if he would be interested in joining the center as a senior fellow. It seemed like a natural fit. In Roth’s nearly 30 years as the executive director of HRW, its budget had grown from $7 million to nearly $100 million, and its staff had gone from 60 to 550 people monitoring more than 100 countries. The “godfather” of human rights, The New York Times called him in a long, admiring overview of his career, noting that Roth “has been an unrelenting irritant to authoritarian governments, exposing human rights abuses with documented research reports that have become the group’s specialty.” HRW played a prominent role in establishing the International Criminal Court, and it helped secure the convictions of Charles Taylor of Liberia, Alberto Fujimori of Peru, and (in a tribunal for the former Yugoslavia) the Bosnian Serb leaders Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladic.

More here.

Prince Harry and the Value of Silence

Patti Davis in The New York Times:

During the early stages of my father’s Alzheimer’s, when he still had lucid moments, I apologized to him for writing an autobiography many years earlier in which I flung open the gates of our troubled family life. He was already talking less at that point, but his eyes told me he understood. I thought of that moment when I read that Prince Harry, in his new memoir, wrote about his father, King Charles, getting between his battling sons and saying, “Please, boys, don’t make my final years a misery.” Time is an unpredictable thing. What will someone’s last memory be? I had the gift of time with my father, which allowed me to apologize, even though a disease hovered between us and clouded our communication. King Charles’s words reveal a man who is aware of his mortality and who would like his offspring to be aware of it as well.

During the early stages of my father’s Alzheimer’s, when he still had lucid moments, I apologized to him for writing an autobiography many years earlier in which I flung open the gates of our troubled family life. He was already talking less at that point, but his eyes told me he understood. I thought of that moment when I read that Prince Harry, in his new memoir, wrote about his father, King Charles, getting between his battling sons and saying, “Please, boys, don’t make my final years a misery.” Time is an unpredictable thing. What will someone’s last memory be? I had the gift of time with my father, which allowed me to apologize, even though a disease hovered between us and clouded our communication. King Charles’s words reveal a man who is aware of his mortality and who would like his offspring to be aware of it as well.

My justification in writing a book I now wish I hadn’t written (and please, don’t go buy it; I’ve written many other books since) was very similar to what I understand to be Harry’s reasoning. I wanted to tell the truth, I wanted to set the record straight. Naïvely, I thought if I put my own feelings and my own truth out there for the world to read, my family might also come to understand me better. Of course, people generally don’t respond well to being embarrassed and exposed in public. And in the ensuing years, I’ve learned something about truth: It’s way more complicated than it seems when we’re young. There isn’t just one truth, our truth — the other people who inhabit our story have their truths as well.

Prince William has, I’m sure, his own take on the physical fight that Harry has described. To really understand the dynamic between the brothers, to broaden the story and make it more complete, William’s truth has to be considered as well. Harry has written that, after William hit him, William told Harry to hit him back, which he declined to do. But by writing about the fight, he’s done exactly that.

The Written World and the Unwritten World

Italo Calvino in The Paris Review:

I belong to that portion of humanity—a minority on the planetary scale but a majority I think among my public—that spends a large part of its waking hours in a special world, a world made up of horizontal lines where the words follow one another one at a time, where every sentence and every paragraph occupies its set place: a world that can be very rich, maybe even richer than the nonwritten one, but that requires me to make a special adjustment to situate myself in it. When I leave the written world to find my place in the other, in what we usually call the world, made up of three dimensions and five senses, populated by billions of our kind, that to me is equivalent every time to repeating the trauma of birth, giving the shape of intelligible reality to a set of confused sensations, and choosing a strategy for confronting the unexpected without being destroyed.

I belong to that portion of humanity—a minority on the planetary scale but a majority I think among my public—that spends a large part of its waking hours in a special world, a world made up of horizontal lines where the words follow one another one at a time, where every sentence and every paragraph occupies its set place: a world that can be very rich, maybe even richer than the nonwritten one, but that requires me to make a special adjustment to situate myself in it. When I leave the written world to find my place in the other, in what we usually call the world, made up of three dimensions and five senses, populated by billions of our kind, that to me is equivalent every time to repeating the trauma of birth, giving the shape of intelligible reality to a set of confused sensations, and choosing a strategy for confronting the unexpected without being destroyed.

This new birth is always accompanied by special rites that signify the entrance into a different life: for example, the rite of putting on my glasses, since I’m nearsighted and read without glasses, while for the farsighted majority the opposite rite is imposed, that is, of taking off the glasses used for reading. Every rite of passage corresponds to a change in mental attitude. When I read, every sentence has to be readily understood, at least in its literal meaning, and has to enable me to formulate an opinion: what I’ve read is true or false, right or wrong, pleasant or unpleasant. In ordinary life, on the other hand, there are always countless circumstances that escape my understanding, from the most general to the most banal: I often find myself facing situations in which I wouldn’t know how to express an opinion, in which I prefer to suspend judgment.

More here.

Anita Pointer (1948 – 2022) Singer/Songwriter

Fred White (1955 – 2023) Drummer

Michael Snow (1928 – 2023) Artist, Filmmaker

Sunday Poem

In language as vivid and violent as the prairie sunlight, Ann Turner’s poems reveal the intensity of the pioneer experience. No one who reads these lines . . . can be unmoved by the lives of the women who undertook this extraordinary journey across a continent.

Amanda Hayes

I carried it all

the way west under

the wagon seat,

black with one gold stripe,

the letters burned

into the cover.

Sometimes when I was frightened

I reached down and touched

THE ODYSSEY

John thought my mind

fixed on clothing,

washing, the children one day

to come (oh, not too soon).

He did not know

of reading by moonlight,

dreams of sweet lands,

horses, ricks, green hills,

men with wine in shallow cups,

and women singing high, then

low, arms outstretched to me.

And I would dance naked

under the stars,

name of the god under my

tongue like a wafer,

my hair black as sky;

and the god would come

and take me by the hand,

lead me to the mountainside,

where he would plunge

into me so deep

I cried his name

sprung from under the tongue.

John doesn’t know

I know. He’s never touched

me that way. No one has.

But I know it in my body

the way a horse smells water

on the wind.

If I see it, I’ll take it.

If I find it, I’ll follow it.

And in one sweet leap

I’ll leave the shuffled

wagon trail, the dirt and flies

and leathered touch

of untaught hands

for crushed pine

under my back,

my eye falling

into the stars.

by Ann Turner

from Grass Songs; Poems of Women’s Journey West

Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1993

Saturday, January 7, 2023

Under the Hood

Zoé Samudzi in Jewish Currents:

Zoé Samudzi in Jewish Currents:

IT’S NOT ALWAYS ADVANTAGEOUS for an exhibition’s reputation to precede it. If critical consensus or controversy about a show’s contents can build anticipation, it can also stand between viewers and the works before them, teaching them to see only what they expect. But it’s all the more disconcerting when the exhibit itself preemptively shapes attendees’ affective responses. Before entering the Philip Guston Now retrospective, which closed at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts in September and is on view until January at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, audiences are invited to take a printed handout: an “Emotional Preparedness Guide” featuring comments from a trauma consultant who advised the show’s curatorial team.

“It is human to shy away from or ignore what makes us uncomfortable,” the flyer begins, “but this practice unintentionally causes harm.” It then encourages museumgoers to “lean into the discomfort of confronting racism on an experiential level,” a process aided by the pursuit of “self-care, rest, education, and community.” The boilerplate social justice language seems designed to facilitate an encounter with violent content while acknowledging its potential to cause distress. But if the warning appears defensive, there’s a reason: It points directly to a previous institutional error. Two years ago, the museums organizing the show made the controversial decision to postpone it on the grounds that the racial imagery in Guston’s work required “additional perspectives and voices” to give it context. Philip Guston Now is their floundering attempt to do so.

More here.

Race was invented by liberals

A conservative review of Kenan Malik’s Not So Black and White by Sohrab Amarhi in Unherd:

A conservative review of Kenan Malik’s Not So Black and White by Sohrab Amarhi in Unherd:

A little more than a year ago, I was sharing a boozy dinner with a prominent conservative pundit when the conversation turned to matters racial. Reflecting on the unrest that had roiled America in the summer of 2020, my companion looked beyond the immediate controversies to venture what he saw as the “real problem”.

White people, he said, have been “too polite” to state obvious racial truths. Like the superiority of Bach, Mozart and Beethoven over all other musical forms and practices. There is no equality between these glories — white glories — and the simplistic rhythms and disconsonant noises that prevail among other peoples (save for East Asians, he granted, who have admirably made Western classical music their own).

I was repulsed. Not, mind you, because I’m any sort of an aesthetic relativist. While liberality demands that we approach each artistic tradition on its own terms, respecting its inner integrity, there finally are objective standards; and by any measure, the Mass in B Minor leaves the drone of the didgeridoo in the Australasian dust. No, what got to me was the weird racialisation of classical music: the idea that Bach & co. embody the achievements not of Christian or even European civilisation, but of the white race, and that this racial “reality” is supposed to bear (unspecified) political consequences.

Race chauvinism is an all too typical “meme” these days, part of a global resurgence of particularism. Ever since the collapse of the Eastern Bloc shuttered the utopian horizon of socialism, questions of belonging and identity have shoved their way back to centre stage, usually at the expense of the more universalist aspirations that used to animate the modern world.

More here.

Dreams of Green Hydrogen

Daniela Gabor and Ndongo Samba Sylla in Boston Review:

Daniela Gabor and Ndongo Samba Sylla in Boston Review:

Few remember Cheikh Anta Diop—the renowned Senegalese historian and Pan-African political leader—as an early prophet of climate change. Yet we should. Writing in 1985, as the world debated an oil glut that was pushing prices to historic lows, Diop envisioned a green Pan-African future. “Powered by hydrogen,” he wrote, “a supersonic plane would only dump tons of water into the atmosphere, whereas one powered by kerosene pollutes in three minutes what the Fontainebleau forest takes a day to absorb.” Imagine, Diop invited his audience, “a university and an African government putting in place, in five years, a small solar plant, somewhere close to the sea, that would produce renewable energy to split seawater into hydrogen and oxygen, and then experiment with liquifying, storage, transport, and other pilot projects.” Green hydrogen, he believed, could build on Africa’s abundant renewable resources.

Diop hoped that developmental states intent on industrialization would coordinate and ultimately unite politically to create the continent’s green hydrogen revolution. Refusing (neo)colonial tropes of “catching up” Africa, the historian versed in chemistry and physics urged African governments to nurture the local capabilities that would pioneer world-leading green hydrogen technologies and build green industries. He described a future where the continent shared these technologies with the rest of the world, one that broke with centuries of colonial—and then neocolonial—extraction. Diop wanted Africa to export green hydrogen technology rather than hydrogen commodities vulnerable to price volatility and neocolonial extractivism.

More here.

The Nokia Risk

Herman Mark Schwartz in Phenomenal World:

Herman Mark Schwartz in Phenomenal World:

In the early 2000s, Finland was the darling of industrial and employment policy analysts everywhere. This small country with a population of 5.5 million and a GDP roughly equal to the state of Oregon experienced what looked like a high tech-led productivity revolution. Real GDP per capita in local currency terms rose 55 percent from 1995 to 2007—nearly double the US increase and close to the pinnacle of the twenty-one richest OECD industrialized economies.

Yet spectacular growth abruptly halted after 2008. GDP continued to rise with population growth, but from 2008 to 2019 real Finnish per capita income declined. The European Central Bank’s dilatory response to the eurozone crisis, and the austerity policies that followed, undoubtedly explain part of this abysmal performance. But an equally large part is due to Finland having many of its growth eggs in a single basket: Nokia. Nokia’s handsets and related telephony equipment accounted for 20 percent of Finnish exports at peak, driving Finland’s current account surplus to nearly 7 percent of GDP. When the Apple iPhone launched in 2007, Nokia’s handset market collapsed, exports fell by half, Finland’s current account swung into deficit, and a decade plus of economic stagnation began.

Finland is not the only economy facing “Nokia risk.”

More here.