Kevin P. Donovan in Boston Review:

Kevin P. Donovan in Boston Review:

When the Grameen Bank and the Bangladeshi academic who helped start it, Muhammad Yunus, won the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize, the event marked the rise of microfinance—the style of global development they pioneered. The prize committee joined supporters such as the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and governments across the Global South in valorizing the idea that making small loans to those typically considered unworthy of credit could “empower” them and “alleviate” poverty.

After experimenting for a number of years, Yunus launched the Grameen Bank in 1983, lending working capital (often as little as a few dollars) to rural women making handicrafts or running shops. Grameen’s appeal was captured in the idea of “social business” that Yunus extolled. While he readily critiqued exclusionary banks and predatory moneylenders, microcredit was hardly opposed to commerce. Instead, it made markets the key domain for fighting global poverty. After all, these were loans not handouts. Lenders expected women to use the money profitably, often grouping Grameen borrowers together so they were jointly liable for individual debts. They believed that social pressure and mutual support would significantly diminish the rate of default—and it did.

More here.

Ed McNally in Sidecar:

Ed McNally in Sidecar: As Justice for Animals rigorously argues, the latest scientific research reveals that the opposite is true: “all vertebrates feel pain subjectively”, many animals “experience emotions like compassion and grief” and display “complicated social learning”. For Nussbaum, the implications are “huge, clearly”. Once we recognise there’s no easy demarcation between human sentience and that of animals, “we can hardly be unchanged in our ethical thinking”.

As Justice for Animals rigorously argues, the latest scientific research reveals that the opposite is true: “all vertebrates feel pain subjectively”, many animals “experience emotions like compassion and grief” and display “complicated social learning”. For Nussbaum, the implications are “huge, clearly”. Once we recognise there’s no easy demarcation between human sentience and that of animals, “we can hardly be unchanged in our ethical thinking”. “

“ In the 20th-century U.S., black-nationalist women—individuals who advocated for black liberation, economic self-sufficiency, racial pride, unity, and political self-determination—emerged as key political leaders on the local, national, and even international levels. When most black women in the U.S. did not have access to the vote, these women boldly confronted the hypocrisy of white America, often drawing upon their knowledge of history. And they did so in public spaces—in mass community meetings, at local parks, and on sidewalks. These women harnessed the power of their voices, passion, and the raw authenticity of their political message to rally black people across the nation and the globe.

In the 20th-century U.S., black-nationalist women—individuals who advocated for black liberation, economic self-sufficiency, racial pride, unity, and political self-determination—emerged as key political leaders on the local, national, and even international levels. When most black women in the U.S. did not have access to the vote, these women boldly confronted the hypocrisy of white America, often drawing upon their knowledge of history. And they did so in public spaces—in mass community meetings, at local parks, and on sidewalks. These women harnessed the power of their voices, passion, and the raw authenticity of their political message to rally black people across the nation and the globe. Poker players have an expression for that moment when you look at your cards and discover you’ve been dealt the luckiest possible hand. It’s called “waking up with aces.” This reminds me of the way that the first lines of poems seem to come out of nowhere. It’s true for the poet, the lines just arriving, as if by dictation or angelic message — as Eliot writes in his essay on Blake, “The idea, of course, simply comes.” And it’s true for the reader, who can only have the same in medias res experience, encountering a line at the top of a page. There’s a shock to this unveiling. All the emails I get begin with some variation on “I hope this finds you well,” but a poem can begin in any kind of way. “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain.” “Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness.” There’s a Wallace Stevens poem that starts “Hi!”

Poker players have an expression for that moment when you look at your cards and discover you’ve been dealt the luckiest possible hand. It’s called “waking up with aces.” This reminds me of the way that the first lines of poems seem to come out of nowhere. It’s true for the poet, the lines just arriving, as if by dictation or angelic message — as Eliot writes in his essay on Blake, “The idea, of course, simply comes.” And it’s true for the reader, who can only have the same in medias res experience, encountering a line at the top of a page. There’s a shock to this unveiling. All the emails I get begin with some variation on “I hope this finds you well,” but a poem can begin in any kind of way. “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain.” “Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness.” There’s a Wallace Stevens poem that starts “Hi!” In M. Night Shyamalan’s new movie, “Knock at the Cabin,” a couple vacationing in rural Pennsylvania with their adopted daughter realize that they are not alone. A group of travellers is watching them from the trees and encroaching on the property. The films of Shyamalan are filled with such uninvited house guests. The big twist in “The Sixth Sense” (1999)—the one that turned its director into the most reliable American brand name in narrative trickery since

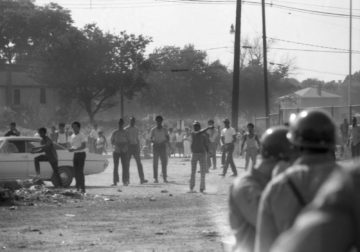

In M. Night Shyamalan’s new movie, “Knock at the Cabin,” a couple vacationing in rural Pennsylvania with their adopted daughter realize that they are not alone. A group of travellers is watching them from the trees and encroaching on the property. The films of Shyamalan are filled with such uninvited house guests. The big twist in “The Sixth Sense” (1999)—the one that turned its director into the most reliable American brand name in narrative trickery since  Black resistance took different forms, from Black residents pelting police with bricks and bottles to Black snipers shooting at police, with the purpose of driving them out of their communities. Black snipers, in particular, fulfilled political fantasies that demonized all forms of Black resistance as pathological and deserving of violent pacification. From 1967 to 1974, the number of police killed in the line of duty jumped from seventy-six to a hundred and thirty-two, the highest annual figure ever. But those totals were dwarfed by the number of young Black men killed by the police in the same period. Hinton reports that, between 1968 and 1974, “Black people were the victims of one in four police killings,” resulting in nearly a hundred Black men under twenty-five dying at the hands of police in each of those years. By comparison, today only one in ten people killed by police is Black, according to the Centers for Disease Control. (Hinton cites this figure but notes that it may represent underreporting.)

Black resistance took different forms, from Black residents pelting police with bricks and bottles to Black snipers shooting at police, with the purpose of driving them out of their communities. Black snipers, in particular, fulfilled political fantasies that demonized all forms of Black resistance as pathological and deserving of violent pacification. From 1967 to 1974, the number of police killed in the line of duty jumped from seventy-six to a hundred and thirty-two, the highest annual figure ever. But those totals were dwarfed by the number of young Black men killed by the police in the same period. Hinton reports that, between 1968 and 1974, “Black people were the victims of one in four police killings,” resulting in nearly a hundred Black men under twenty-five dying at the hands of police in each of those years. By comparison, today only one in ten people killed by police is Black, according to the Centers for Disease Control. (Hinton cites this figure but notes that it may represent underreporting.) As I worked on this publication, I came to cherish Motherwell’s drawings more and more. Although they are the drawings of a painter, and drawing is not the medium he is principally known for, it is here, in his drawings, that we see his mind at work most clearly and most vividly. In his drawings, we can see the quintessence of depth and breadth of his work, from the abstracted figures of the 1940s to his purely automatist Lyric Suite (1965) and spare geometric “Open” series of the 1960s, to his luminous graphic responses to James Joyce during the 1980s. Although his drawings are related to—and sometimes provided the seeds for—his paintings, he revered drawing as a unique practice of its own, which had its own character and involved particular demands. For Motherwell, the medium was “the only thing in human existence that has precisely the same range of sensed feeling as people themselves do. And it is only when you think of the medium as having the same potential as another human being, that you begin to see the nature of the artist’s involvement.”

As I worked on this publication, I came to cherish Motherwell’s drawings more and more. Although they are the drawings of a painter, and drawing is not the medium he is principally known for, it is here, in his drawings, that we see his mind at work most clearly and most vividly. In his drawings, we can see the quintessence of depth and breadth of his work, from the abstracted figures of the 1940s to his purely automatist Lyric Suite (1965) and spare geometric “Open” series of the 1960s, to his luminous graphic responses to James Joyce during the 1980s. Although his drawings are related to—and sometimes provided the seeds for—his paintings, he revered drawing as a unique practice of its own, which had its own character and involved particular demands. For Motherwell, the medium was “the only thing in human existence that has precisely the same range of sensed feeling as people themselves do. And it is only when you think of the medium as having the same potential as another human being, that you begin to see the nature of the artist’s involvement.” Nigel Biggar retired a few months ago from the Regius Professorship of Moral and Pastoral Theology at Oxford. He is a notable figure in the world of moral philosophy, not only because of his distinguished academic career as an ethicist but also because of his persistent refusal to observe the conventional pieties which characterise so much that is written in his field.

Nigel Biggar retired a few months ago from the Regius Professorship of Moral and Pastoral Theology at Oxford. He is a notable figure in the world of moral philosophy, not only because of his distinguished academic career as an ethicist but also because of his persistent refusal to observe the conventional pieties which characterise so much that is written in his field. A: I don’t even have cable anymore.

A: I don’t even have cable anymore. For most of 2022 I was quietly working on my second book,

For most of 2022 I was quietly working on my second book,  The story of Babel is the best metaphor I’ve found for making sense of the momentous sociological, cultural, and epistemological changes that occurred in many nations in the early 2010s, which gave us the chaos, fragmentation, and outrage that began to set in by the mid-2010s. There are many causes of the transformation, but I believe that the largest single cause was the rapid conversion,

The story of Babel is the best metaphor I’ve found for making sense of the momentous sociological, cultural, and epistemological changes that occurred in many nations in the early 2010s, which gave us the chaos, fragmentation, and outrage that began to set in by the mid-2010s. There are many causes of the transformation, but I believe that the largest single cause was the rapid conversion,