Olga Tokarczuk at Salmagundi:

I would like to focus on a special way of predicting the future, and to invite you to take a trip down paths that are rarely trodden by humanists. As we are living at a time of unusual uncertainty and anxiety about what will happen next, this topic is on many people’s minds, prompting us to ask: “What is our future going to be like?” And also: “Can we foresee it to any degree at all?” When I say “our future” I’m not thinking of the next few years, but rather about the gradual processes whose effects will be visible several centuries from now.

I would like to focus on a special way of predicting the future, and to invite you to take a trip down paths that are rarely trodden by humanists. As we are living at a time of unusual uncertainty and anxiety about what will happen next, this topic is on many people’s minds, prompting us to ask: “What is our future going to be like?” And also: “Can we foresee it to any degree at all?” When I say “our future” I’m not thinking of the next few years, but rather about the gradual processes whose effects will be visible several centuries from now.

In ages past, various ways of predicting the future developed dynamically – dating back to oracles and predictions based on observations of nature, or by apparently communicating with supernatural forces corresponding to the ongoing demands of society. I shall provide some examples from the ancient world, where alongside astrology, with its centuries-old tradition, various schools of “something-mancy” co-existed, some more and some less obvious. The more obvious ones include oneiromancy, as in divination by dreams; arithmancy, which uses numbers for predictive purposes; cheiromancy, forreading the future from the palm lines; or ceromancy, which bases its predictions on wax poured into water, and which in Poland is also a familiar folk custom associated with St. Andrew’s Eve.

more here.

She too was a link, though a precious one, the only living connection to the ghost I stalked. Katherine Mansfield. The romantic renegade writer, older by five years at her death at 34 in January 1923 than I was/am on this June day in 1975.

She too was a link, though a precious one, the only living connection to the ghost I stalked. Katherine Mansfield. The romantic renegade writer, older by five years at her death at 34 in January 1923 than I was/am on this June day in 1975. California’s population growth was one of defining trends of 20th-century America. From 1900 to 1950 the population increased 500%, going from two million to ten million. Then things really exploded, and by the year 2000 the state’s population had climbed to 34 million, making California the most populous state in America. People have been lured west for a variety of reasons, from the gold rush to Hollywood dreams, but beyond riches and fame there has been also the promise of the sunny California lifestyle, one captured by LIFE staff photographer

California’s population growth was one of defining trends of 20th-century America. From 1900 to 1950 the population increased 500%, going from two million to ten million. Then things really exploded, and by the year 2000 the state’s population had climbed to 34 million, making California the most populous state in America. People have been lured west for a variety of reasons, from the gold rush to Hollywood dreams, but beyond riches and fame there has been also the promise of the sunny California lifestyle, one captured by LIFE staff photographer  Loneliness can be difficult to study empirically because it is entirely subjective. Social isolation, a related condition, is different — it’s an objective measure of how few relationships a person has. The experience of loneliness has to be self-reported, although researchers have developed tools such as the

Loneliness can be difficult to study empirically because it is entirely subjective. Social isolation, a related condition, is different — it’s an objective measure of how few relationships a person has. The experience of loneliness has to be self-reported, although researchers have developed tools such as the  Someone asks: why is “Jap” a slur? It’s the natural shortening of “Japanese person”, just as “Brit” is the natural shortening of “British person”. Nobody says “Brit” is a slur. Why should “Jap” be?

Someone asks: why is “Jap” a slur? It’s the natural shortening of “Japanese person”, just as “Brit” is the natural shortening of “British person”. Nobody says “Brit” is a slur. Why should “Jap” be? After years of debates and discussions, nations have agreed on a High Seas Treaty to protect marine biodiversity and provide oversight of international waters. It is being lauded by researchers as an important step for conservation that encourages international research collaboration without hindering science.

After years of debates and discussions, nations have agreed on a High Seas Treaty to protect marine biodiversity and provide oversight of international waters. It is being lauded by researchers as an important step for conservation that encourages international research collaboration without hindering science. In May 2014, Greg Lukianoff invited me to lunch to talk about something he was seeing on college campuses that disturbed him. Greg is the president of FIRE (the

In May 2014, Greg Lukianoff invited me to lunch to talk about something he was seeing on college campuses that disturbed him. Greg is the president of FIRE (the  UNTIL THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

UNTIL THE NINETEENTH CENTURY The map of Balanchine’s life once he left Russia in 1924 and until he finally settled into the New York City Ballet in 1948 may read as a kind of wandering, but his life as an artist was made of circles: the revolving of the repertory, the return to old ballets, the rethinking and recalibration of steps and phrases. To the dismay of his audience, for instance, Balanchine pared back the iconic

The map of Balanchine’s life once he left Russia in 1924 and until he finally settled into the New York City Ballet in 1948 may read as a kind of wandering, but his life as an artist was made of circles: the revolving of the repertory, the return to old ballets, the rethinking and recalibration of steps and phrases. To the dismay of his audience, for instance, Balanchine pared back the iconic  One afternoon a few weeks ago, Alicea Hotchkiss’s 14-year-old son, Eli, came home from his high school in Tampa with a question about something a classmate had said to him. He’d heard the student use the word “gay” as an insult, so Eli responded the way he always does when this happens. “Hey,” Eli said, “my dad’s gay.” But this time, Eli told his mom, the other kid offered a startling rebuke: You’re not allowed to say that at school.

One afternoon a few weeks ago, Alicea Hotchkiss’s 14-year-old son, Eli, came home from his high school in Tampa with a question about something a classmate had said to him. He’d heard the student use the word “gay” as an insult, so Eli responded the way he always does when this happens. “Hey,” Eli said, “my dad’s gay.” But this time, Eli told his mom, the other kid offered a startling rebuke: You’re not allowed to say that at school. I was never into house plants until I bought one on a whim—a prayer plant, it was called, a lush, leafy thing with painterly green spots and ribs of bright red veins. The night I brought it home I heard a rustling in my room. Had something scurried? A mouse? Three jumpy nights passed before I realized what was happening: The plant was moving. During the day, its leaves would splay flat, sunbathing, but at night they’d clamber over one another to stand at attention, their stems steadily rising as the leaves turned vertical, like hands in prayer.

I was never into house plants until I bought one on a whim—a prayer plant, it was called, a lush, leafy thing with painterly green spots and ribs of bright red veins. The night I brought it home I heard a rustling in my room. Had something scurried? A mouse? Three jumpy nights passed before I realized what was happening: The plant was moving. During the day, its leaves would splay flat, sunbathing, but at night they’d clamber over one another to stand at attention, their stems steadily rising as the leaves turned vertical, like hands in prayer. The Polish poet Adam Zagajewski’s great poem “To Go to Lvov” has a special importance for many young poets in different languages. That poem weaves the historical and the personal, the rhythms of cataclysm and of ordinary life, loss and persistence, all embodied in Zagajewski’s native city. “To Go to Lvov” has provided a model — intensely local, adamantly not nationalistic — for poems rooted in Philadelphia, Buenos Aires and Lahore.

The Polish poet Adam Zagajewski’s great poem “To Go to Lvov” has a special importance for many young poets in different languages. That poem weaves the historical and the personal, the rhythms of cataclysm and of ordinary life, loss and persistence, all embodied in Zagajewski’s native city. “To Go to Lvov” has provided a model — intensely local, adamantly not nationalistic — for poems rooted in Philadelphia, Buenos Aires and Lahore.

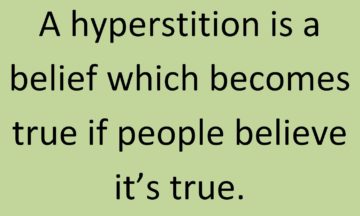

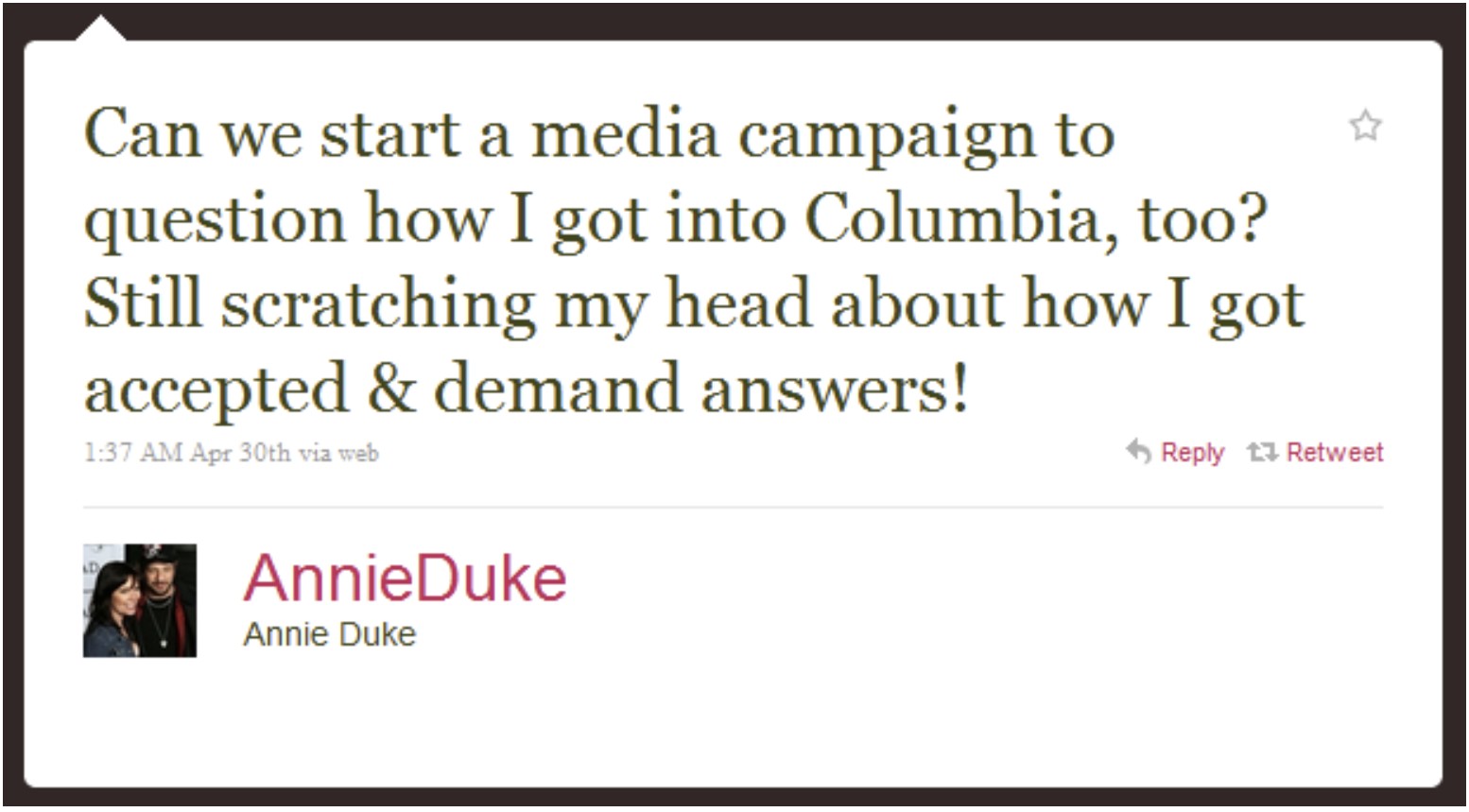

Human behavior is often paradoxical. We show humility to prove we’re better than other people, we bravely defy social norms so that people will praise us, and we donate to charity anonymously to get credit for not caring about getting credit. Here, I argue that these and other social paradoxes have a common thread: they are all attempts to signal a trait while concealing the fact that one is signaling the trait. Such self-negating signals emerge from the interaction of two cognitive abilities: 1) cue-based inference, and 2) recursive mentalizing. If agents can model each other’s mental states, including their intentions to signal positive traits, then intentional signals of positive traits can, themselves, become cues of negative traits. The result is that status-seeking and virtue-signaling are forced to occur covertly, without becoming common knowledge among signalers or recipients. Social paradoxes also play a crucial role in enabling intergroup dominance by inhibiting common knowledge of the group’s dominance-seeking tactics, which would otherwise disrupt coordination by eliciting moral disapproval. The analysis of social paradoxes can explain a variety of puzzling aspects of human social life, including the cultural evolution of status symbols, the function of sacred values, and the nature of political belief systems.

Human behavior is often paradoxical. We show humility to prove we’re better than other people, we bravely defy social norms so that people will praise us, and we donate to charity anonymously to get credit for not caring about getting credit. Here, I argue that these and other social paradoxes have a common thread: they are all attempts to signal a trait while concealing the fact that one is signaling the trait. Such self-negating signals emerge from the interaction of two cognitive abilities: 1) cue-based inference, and 2) recursive mentalizing. If agents can model each other’s mental states, including their intentions to signal positive traits, then intentional signals of positive traits can, themselves, become cues of negative traits. The result is that status-seeking and virtue-signaling are forced to occur covertly, without becoming common knowledge among signalers or recipients. Social paradoxes also play a crucial role in enabling intergroup dominance by inhibiting common knowledge of the group’s dominance-seeking tactics, which would otherwise disrupt coordination by eliciting moral disapproval. The analysis of social paradoxes can explain a variety of puzzling aspects of human social life, including the cultural evolution of status symbols, the function of sacred values, and the nature of political belief systems.