Zack Savitsky in Quanta Magazine:

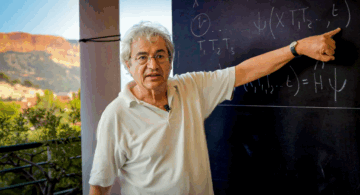

Sitting outside a Catholic church on the French Riviera, Carlo Rovelli jutted his head forward and backward, imitating a pigeon trotting by. Pigeons bob their heads, he told me, not only to stabilize their vision but also to gauge distances(opens a new tab) to objects — compensating for their limited binocular vision. “It’s all perspectival,” he said.

Sitting outside a Catholic church on the French Riviera, Carlo Rovelli jutted his head forward and backward, imitating a pigeon trotting by. Pigeons bob their heads, he told me, not only to stabilize their vision but also to gauge distances(opens a new tab) to objects — compensating for their limited binocular vision. “It’s all perspectival,” he said.

A theoretical physicist affiliated with Aix-Marseille University, Rovelli studies how we perceive reality from our limited vantage point. His research is wide-ranging, running the gamut from quantum information to black holes, and often delves into the history and philosophy of science. In the late 1980s, he helped develop a theory called loop quantum gravity that aims to describe the quantum underpinnings of space and time. A decade later, he proposed a new “relational” interpretation of quantum mechanics, which goes so far as to suggest that there is no objective reality whatsoever, only perspectives on reality — be they a physicist’s or a pigeon’s.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

G

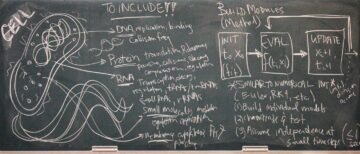

G A human cell swarms with trillions of molecules, including some 42 million proteins and a plethora of carbohydrates, lipids, and nucleic acids. Crowded with organelles and other structures, the cell boasts an intricate organization that makes baroque architecture seem plain. Its cytoplasm is a frenzied chemical lab, with molecules continuously reacting, rearranging, and reshaping. In the nucleus, thousands of genes are constantly switching on and off to turn the seeming chaos into concerted actions that help the cell survive and reproduce.

A human cell swarms with trillions of molecules, including some 42 million proteins and a plethora of carbohydrates, lipids, and nucleic acids. Crowded with organelles and other structures, the cell boasts an intricate organization that makes baroque architecture seem plain. Its cytoplasm is a frenzied chemical lab, with molecules continuously reacting, rearranging, and reshaping. In the nucleus, thousands of genes are constantly switching on and off to turn the seeming chaos into concerted actions that help the cell survive and reproduce. Already in 1967, the same year When She Was Good came out, the first samples of Portnoy’s Complaint were issued in wide-circulation magazines like Esquire and Sport, as well as the highbrow Partisan Review. Indeed, it was there, in that mainstay of the New York intelligentsia, that Roth signaled his departure from the magazine’s austere norms with the chapter entitled “Whacking Off.” Solotaroff’s new paperback journal New American Review ran two excerpted chapters of the novel, the first almost two years before the book’s appearance, the second numbering no fewer than twenty-eight thousand words.

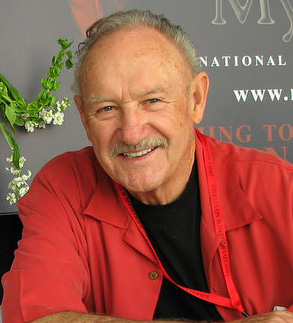

Already in 1967, the same year When She Was Good came out, the first samples of Portnoy’s Complaint were issued in wide-circulation magazines like Esquire and Sport, as well as the highbrow Partisan Review. Indeed, it was there, in that mainstay of the New York intelligentsia, that Roth signaled his departure from the magazine’s austere norms with the chapter entitled “Whacking Off.” Solotaroff’s new paperback journal New American Review ran two excerpted chapters of the novel, the first almost two years before the book’s appearance, the second numbering no fewer than twenty-eight thousand words. The potential for AI to improve weather forecasting and climate modelling (which also takes a long time and uses a lot of energy)

The potential for AI to improve weather forecasting and climate modelling (which also takes a long time and uses a lot of energy)  As someone who has spent decades studying the evolution of nuclear energy, I’ve seen its emergence as a promising transformative technology, its stagnation as a consequence of dramatic accidents and its current re-emergence as a potential solution to the challenges of global warming.

As someone who has spent decades studying the evolution of nuclear energy, I’ve seen its emergence as a promising transformative technology, its stagnation as a consequence of dramatic accidents and its current re-emergence as a potential solution to the challenges of global warming. The central insight that these disparate thinkers took from Kant is that the world isn’t simply a thing, or a collection of things, given to us to perceive. Rather, our minds help create the reality we experience. In particular, Kant argued that time, space, and causality, which we ordinarily take for granted as the most basic aspects of the world, are better understood as forms imposed on the world by the human mind.

The central insight that these disparate thinkers took from Kant is that the world isn’t simply a thing, or a collection of things, given to us to perceive. Rather, our minds help create the reality we experience. In particular, Kant argued that time, space, and causality, which we ordinarily take for granted as the most basic aspects of the world, are better understood as forms imposed on the world by the human mind. Horror is ubiquitous on TV at this time of year, and those of us who love a good scare—myself very much included—usually look forward to it. Unfortunately, October 2025’s selection of IP expansions (

Horror is ubiquitous on TV at this time of year, and those of us who love a good scare—myself very much included—usually look forward to it. Unfortunately, October 2025’s selection of IP expansions ( IN THESE PROFOUNDLY unsettling times, literary criticism can seem a little frivolous. We’re no longer slouching toward some imagined autocratic future; we’re midway through the dissolution of the American experiment. We’ve got concentration camps and mass deportations, the senseless dismantlement of essential federal agencies, military personnel on foot patrol in our nation’s capital. There’s a relentless assault on public media, public education, public service, public health, and anything else that an earlier generation would have reasonably considered to be in the public’s interest. It’s dystopian and thoroughly demoralizing. And the most we can manage, it would seem, is to twiddle our thumbs like so many complicit functionaries, doomscrolling against the inevitable.

IN THESE PROFOUNDLY unsettling times, literary criticism can seem a little frivolous. We’re no longer slouching toward some imagined autocratic future; we’re midway through the dissolution of the American experiment. We’ve got concentration camps and mass deportations, the senseless dismantlement of essential federal agencies, military personnel on foot patrol in our nation’s capital. There’s a relentless assault on public media, public education, public service, public health, and anything else that an earlier generation would have reasonably considered to be in the public’s interest. It’s dystopian and thoroughly demoralizing. And the most we can manage, it would seem, is to twiddle our thumbs like so many complicit functionaries, doomscrolling against the inevitable. A

A We’ve moved beyond what the magazine n+1 identified as the unadorned qualities of post-2008 cityscapes. That insubstantial, flat and gray “fast-casual modernism” is complemented by a social-media-approved cookie-cutter skin that has been thrust upon our major and midsize cities in a dismal consensus. It’s no surprise that New York is getting its very own versions of two neo-yuppie Los Angeles mainstays: the meme-ified health-food store Erewhon and the Los Feliz cafe Maru (which I love, of course). America’s two largest cities have most quickly been reshaped by the internet, succumbing to an epidemic of increasingly blank streets for the moneyed classes, the bicoastal and the terminally online people who covet luxury. It’s possible now to walk down Columbus Avenue and mistake it for Abbot Kinney in Venice Beach.

We’ve moved beyond what the magazine n+1 identified as the unadorned qualities of post-2008 cityscapes. That insubstantial, flat and gray “fast-casual modernism” is complemented by a social-media-approved cookie-cutter skin that has been thrust upon our major and midsize cities in a dismal consensus. It’s no surprise that New York is getting its very own versions of two neo-yuppie Los Angeles mainstays: the meme-ified health-food store Erewhon and the Los Feliz cafe Maru (which I love, of course). America’s two largest cities have most quickly been reshaped by the internet, succumbing to an epidemic of increasingly blank streets for the moneyed classes, the bicoastal and the terminally online people who covet luxury. It’s possible now to walk down Columbus Avenue and mistake it for Abbot Kinney in Venice Beach. Cognitivism, which has permeated society—as evidenced by the omnipresence of the terms “cognitive” and “cognition”—has perpetuated a traditional view of thought and intelligence as phenomena of inextricable complexity, and therefore phenomena that we can hardly imagine recreating artificially. This approach has prevented us from anticipating and continues to prevent us from understanding what is happening. Behaviorism, on the other hand, allows us to apprehend complexity through the simple processes from which it emerges and provides the framework for understanding current AI. According to this approach, here is what is essential to understand about psychology: the environment shapes the behavior of organisms via two processes, natural selection and associative learning; the first process structures the brain over generations, establishing a “pre-wiring” that provides the basis upon which the second process structures behaviors over the course of the individual’s life.

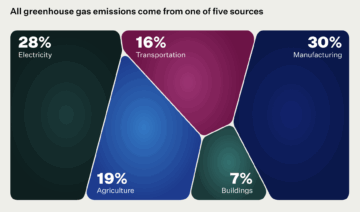

Cognitivism, which has permeated society—as evidenced by the omnipresence of the terms “cognitive” and “cognition”—has perpetuated a traditional view of thought and intelligence as phenomena of inextricable complexity, and therefore phenomena that we can hardly imagine recreating artificially. This approach has prevented us from anticipating and continues to prevent us from understanding what is happening. Behaviorism, on the other hand, allows us to apprehend complexity through the simple processes from which it emerges and provides the framework for understanding current AI. According to this approach, here is what is essential to understand about psychology: the environment shapes the behavior of organisms via two processes, natural selection and associative learning; the first process structures the brain over generations, establishing a “pre-wiring” that provides the basis upon which the second process structures behaviors over the course of the individual’s life. Although climate change will have serious consequences—particularly for people in the poorest countries—it will not lead to humanity’s demise. People will be able to live and thrive in most places on Earth for the foreseeable future. Emissions projections have gone down, and with the right policies and investments, innovation will allow us to drive emissions down much further.

Although climate change will have serious consequences—particularly for people in the poorest countries—it will not lead to humanity’s demise. People will be able to live and thrive in most places on Earth for the foreseeable future. Emissions projections have gone down, and with the right policies and investments, innovation will allow us to drive emissions down much further.