Category: Recommended Reading

The Eros of Shirley Hazzard

David Mason at the Hudson Review:

Among the literary genres, biography appears to be thriving. Perhaps it satisfies some element of life writing we also get from fiction, adding a dose of gossip and the illusion that we can actually know the truth of other people’s lives. There is always more than one way to tell a story. Some good recent biographies have been thematic or experimental: Katherine Rundell on John Donne, Frances Wilson on D. H. Lawrence, Andrew S. Curran on Diderot, Clare Carlisle on Kierkegaard. We have authoritative doorstoppers from Langdon Hammer on James Merrill to Heather Clark’s numbingly detailed book on Sylvia Plath. And we find a happy medium-sized biography in Mark Eisner’s on Neruda or Ann-Marie Priest’s on the great Australian poet Gwen Harwood. Among the best of these, Brigitta Olubas’ Shirley Hazzard: A Writing Life is not overstuffed or particularly arcane in structure, not weighted down with newly discovered scandal, but lucidly and even gracefully organized, guided by a compelling thesis.[1] Olubas believes, and I agree, that Hazzard pursued one erotic object more than all others, poetry, which is inseparable from Eros in its other meanings. “This . . . large belief in romantic and sexual love stands behind all Shirley Hazzard’s writing,” Olubas tells us. “It is aligned with her sense of human connectedness and above all with poetry, which is at heart for her a way of being human.”

Among the literary genres, biography appears to be thriving. Perhaps it satisfies some element of life writing we also get from fiction, adding a dose of gossip and the illusion that we can actually know the truth of other people’s lives. There is always more than one way to tell a story. Some good recent biographies have been thematic or experimental: Katherine Rundell on John Donne, Frances Wilson on D. H. Lawrence, Andrew S. Curran on Diderot, Clare Carlisle on Kierkegaard. We have authoritative doorstoppers from Langdon Hammer on James Merrill to Heather Clark’s numbingly detailed book on Sylvia Plath. And we find a happy medium-sized biography in Mark Eisner’s on Neruda or Ann-Marie Priest’s on the great Australian poet Gwen Harwood. Among the best of these, Brigitta Olubas’ Shirley Hazzard: A Writing Life is not overstuffed or particularly arcane in structure, not weighted down with newly discovered scandal, but lucidly and even gracefully organized, guided by a compelling thesis.[1] Olubas believes, and I agree, that Hazzard pursued one erotic object more than all others, poetry, which is inseparable from Eros in its other meanings. “This . . . large belief in romantic and sexual love stands behind all Shirley Hazzard’s writing,” Olubas tells us. “It is aligned with her sense of human connectedness and above all with poetry, which is at heart for her a way of being human.”

more here.

Small Fires: An Epic in the Kitchen

Marian Bull at n+1:

IN A 2013 AFTERWORD to the combined reprint of her memoirs Comfort Me with Apples and Tender at the Bone, Ruth Reichl reflects back on writing the latter: “When I was writing Tender at the Bone, the food memoir didn’t exist. . . . As I was trying to think about telling my story through food, it occurred to me that the recipes could function the way photographs did in other people’s books.” While MFK Fisher, Julia Child, Elizabeth David, and other 20th-century food writers had dabbled in autobiography, the 21st-century food memoir owes itself to Reichl, whose 1998 bestseller created a template and boom market for others like it. The book traces her evolution as a person through the food she cooked and ate as a child, then as a teenager, then as a young woman, each chapter’s lesson or metaphor punctuated with a recipe. From the first chapter, food is a cipher for emotion and personality; recipes refract a time, a place, a feeling. While some people may look back at a photo album to remember their own emotional history, Reichl conjures up a lifetime of meals.

IN A 2013 AFTERWORD to the combined reprint of her memoirs Comfort Me with Apples and Tender at the Bone, Ruth Reichl reflects back on writing the latter: “When I was writing Tender at the Bone, the food memoir didn’t exist. . . . As I was trying to think about telling my story through food, it occurred to me that the recipes could function the way photographs did in other people’s books.” While MFK Fisher, Julia Child, Elizabeth David, and other 20th-century food writers had dabbled in autobiography, the 21st-century food memoir owes itself to Reichl, whose 1998 bestseller created a template and boom market for others like it. The book traces her evolution as a person through the food she cooked and ate as a child, then as a teenager, then as a young woman, each chapter’s lesson or metaphor punctuated with a recipe. From the first chapter, food is a cipher for emotion and personality; recipes refract a time, a place, a feeling. While some people may look back at a photo album to remember their own emotional history, Reichl conjures up a lifetime of meals.

more here.

On killing charles Dickens

Zadie Smith in The New Yorker:

For the first thirty years of my life, I lived within a one-mile radius of Willesden Green Tube Station. It’s true I went to college—I even moved to East London for a bit—but such interludes were brief. I soon returned to my little corner of North West London. Then suddenly, quite abruptly, I left not just the city but England itself. First for Rome, then Boston, and then my beloved New York, where I stayed ten years. When friends asked why I’d left the country, I’d sometimes answer with a joke: Because I don’t want to write a historical novel. Perhaps it was an in-joke: only other English novelists really understood what I meant by it. And there were other, more obvious reasons. My English father had died. My Jamaican mother was pursuing a romance in Ghana. I myself had married an Irish poet who liked travel and adventure and had left the island of his birth at the age of eighteen. My ties to England seemed to be evaporating. I would not say I was entirely tired of London. No, I was not yet—in Samuel Johnson’s famous formulation—“tired of life.” But I was definitely weary of London’s claustrophobic literary world, or at least the role I had been assigned within it: multicultural (aging) wunderkind. Off I went.

For the first thirty years of my life, I lived within a one-mile radius of Willesden Green Tube Station. It’s true I went to college—I even moved to East London for a bit—but such interludes were brief. I soon returned to my little corner of North West London. Then suddenly, quite abruptly, I left not just the city but England itself. First for Rome, then Boston, and then my beloved New York, where I stayed ten years. When friends asked why I’d left the country, I’d sometimes answer with a joke: Because I don’t want to write a historical novel. Perhaps it was an in-joke: only other English novelists really understood what I meant by it. And there were other, more obvious reasons. My English father had died. My Jamaican mother was pursuing a romance in Ghana. I myself had married an Irish poet who liked travel and adventure and had left the island of his birth at the age of eighteen. My ties to England seemed to be evaporating. I would not say I was entirely tired of London. No, I was not yet—in Samuel Johnson’s famous formulation—“tired of life.” But I was definitely weary of London’s claustrophobic literary world, or at least the role I had been assigned within it: multicultural (aging) wunderkind. Off I went.

More here.

Anti-ageing protein injection boosts monkeys’ memories

Lilly Tozer in Nature:

Injecting ageing monkeys with a ‘longevity factor’ protein can improve their cognitive function, a study reveals. The findings, published on 3 July in Nature Aging1, could lead to new treatments for neurodegenerative diseases.

Injecting ageing monkeys with a ‘longevity factor’ protein can improve their cognitive function, a study reveals. The findings, published on 3 July in Nature Aging1, could lead to new treatments for neurodegenerative diseases.

It is the first time that restoring levels of klotho — a naturally occurring protein that declines in our bodies with age — has been shown to improve cognition in a primate. Previous research on mice had shown that injections of klotho can extend the animals’ lives and increases synaptic plasticity2 — the capacity to control communication between neurons, at junctions called synapses. “Given the close genetic and physiological parallels between primates and humans, this could suggest potential applications for treating human cognitive disorders,” says Marc Busche, a neurologist at the UK Dementia Research Institute group at University College London. The protein is named after the Greek goddess Clotho, one of the Fates, who spins the thread of life.

More here.

Wednesday Poem

Bonfire Opera, Small Kindnesses and Omens

In those days, there was a woman in our circle

who was known, not only for her beauty,

but for taking off all her clothes and singing opera.

And sure enough, as the night wore on and the stars

emerged to stare at their reflections on the sea,

and everyone had drunk a little wine,

she began to disrobe, loose her great bosom,

and the tender belly, pale in the moonlight,

the Viking hips, and to let her torn raiment

fall to the sand as we looked up from the flames.

And then a voice lifted into the dark, high and clear

as a flock of blackbirds. And everything was very still,

the way the congregation quiets when the priest

prays over the incense, and the smoke wafts

up into the rafters. I wanted to be that free

inside the body, the doors of pleasure

opening, one after the next, an arpeggio

climbing the ladder of sky. And all the while

she was singing and wading into the water

until it rose up to her waist and then lapped

at the underside of her breasts, and the aria

drifted over us, her soprano spare and sharp

in the night air. And even though I was young,

somehow, in that moment, I heard it,

the song inside the song, and I knew then

that this was not the hymn of promise

but the body’s bright wailing against its limits.

A bird caught in a cathedral—the way it tries

to escape by throwing itself, again and again,

against the stained glass.

by Danusha Laméris

from American Poetry Review VOL. 46/No.3

Tuesday, July 4, 2023

Consciousness Vs Intelligence

Pasolini on Caravaggio’s Artificial Light

Pier Paolo Pasolini at The Paris Review:

Anything I could ever know about Caravaggio derives from what Roberto Longhi had to say about him. Yes, Caravaggio was a great inventor, and thus a great realist. But what did Caravaggio invent? In answering this rhetorical question, I cannot help but stick to Longhi’s example. First, Caravaggio invented a new world that, to invoke the language of cinematography, one might call profilmic. By this I mean everything that appears in front of the camera. Caravaggio invented an entire world to place in front of his studio’s easel: new kinds of people (in both a social and characterological sense), new kinds of objects, and new kinds of landscapes. Second: Caravaggio invented a new kind of light. He replaced the universal, platonic light of the Renaissance with a quotidian and dramatic one. Caravaggio invented both this new kind of light and new kinds of people and things because he had seen them in reality. He realized that there were individuals around him who had never appeared in the great altarpieces and frescoes, individuals who had been marginalized by the cultural ideology of the previous two centuries. And there were hours of the day—transient, yet unequivocal in their lighting—which had never been reproduced, and which were pushed so far from habit and use that they had become scandalous, and therefore repressed. So repressed, in fact, that painters (and people in general) probably didn’t see them at all until Caravaggio.

Anything I could ever know about Caravaggio derives from what Roberto Longhi had to say about him. Yes, Caravaggio was a great inventor, and thus a great realist. But what did Caravaggio invent? In answering this rhetorical question, I cannot help but stick to Longhi’s example. First, Caravaggio invented a new world that, to invoke the language of cinematography, one might call profilmic. By this I mean everything that appears in front of the camera. Caravaggio invented an entire world to place in front of his studio’s easel: new kinds of people (in both a social and characterological sense), new kinds of objects, and new kinds of landscapes. Second: Caravaggio invented a new kind of light. He replaced the universal, platonic light of the Renaissance with a quotidian and dramatic one. Caravaggio invented both this new kind of light and new kinds of people and things because he had seen them in reality. He realized that there were individuals around him who had never appeared in the great altarpieces and frescoes, individuals who had been marginalized by the cultural ideology of the previous two centuries. And there were hours of the day—transient, yet unequivocal in their lighting—which had never been reproduced, and which were pushed so far from habit and use that they had become scandalous, and therefore repressed. So repressed, in fact, that painters (and people in general) probably didn’t see them at all until Caravaggio.

more here.

Thunderclap: A Memoir of Art & Life & Sudden Death

Norma Clarke at Literary Review:

‘We see pictures in time and place … They are fragments of our lives, moments of existence that may be as unremarkable as rain or as startling as a clap of thunder,’ Cumming writes. A love of Dutch art and a passion for looking at pictures were bequeathed to Cumming by her artist parents. She wrote about her mother’s fragmented, mysterious early life in On Chapel Sands (2019). In Thunderclap it is Laura’s father, James Cumming, who takes centre stage, and like On Chapel Sands the book is infused with love – of parents, childhood, pictures and words. It is at once deeply personal and inclusive, because it is about the shared experience of looking at pictures and the shared desire to know and understand what these ‘moments of existence’ mean. I liked reading Thunderclap so much that I immediately reread On Chapel Sands. Together, these books are a remarkable experiment in form as well as a richly satisfying extended meditation on art, life and death.

‘We see pictures in time and place … They are fragments of our lives, moments of existence that may be as unremarkable as rain or as startling as a clap of thunder,’ Cumming writes. A love of Dutch art and a passion for looking at pictures were bequeathed to Cumming by her artist parents. She wrote about her mother’s fragmented, mysterious early life in On Chapel Sands (2019). In Thunderclap it is Laura’s father, James Cumming, who takes centre stage, and like On Chapel Sands the book is infused with love – of parents, childhood, pictures and words. It is at once deeply personal and inclusive, because it is about the shared experience of looking at pictures and the shared desire to know and understand what these ‘moments of existence’ mean. I liked reading Thunderclap so much that I immediately reread On Chapel Sands. Together, these books are a remarkable experiment in form as well as a richly satisfying extended meditation on art, life and death.

more here.

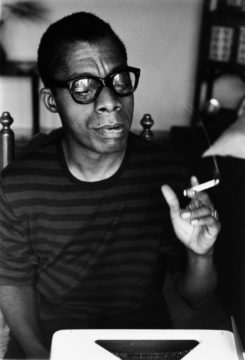

James Baldwin in Turkey

Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi in The Yale Review:

The eleven-minute black and white documentary, James Baldwin: From Another Place, directed by Sedat Pakay and filmed in Istanbul in May 1970, opens with a shot of Baldwin lying supine in a large bed in a sparsely decorated room. The curtains are closed. Baldwin throws back the covers and gets up; he is wearing nothing but a pair of white briefs. He turns his back to the camera and opens the curtains. A sharp Mediterranean light floods in. Baldwin scratches the small of his back, and we hear him say in voiceover: “I suppose that many people do blame me for being out of the States as often as I am, but one can’t afford to worry about that because one does, you know, you do what you have to do the way you have to do it. And as someone who is outside of the States you realize that it’s impossible to get out, the American powers are everywhere.” The camera pans over the glittering Bosphorus Strait as American ships glide silently through the passage connecting Asia and Europe.

The eleven-minute black and white documentary, James Baldwin: From Another Place, directed by Sedat Pakay and filmed in Istanbul in May 1970, opens with a shot of Baldwin lying supine in a large bed in a sparsely decorated room. The curtains are closed. Baldwin throws back the covers and gets up; he is wearing nothing but a pair of white briefs. He turns his back to the camera and opens the curtains. A sharp Mediterranean light floods in. Baldwin scratches the small of his back, and we hear him say in voiceover: “I suppose that many people do blame me for being out of the States as often as I am, but one can’t afford to worry about that because one does, you know, you do what you have to do the way you have to do it. And as someone who is outside of the States you realize that it’s impossible to get out, the American powers are everywhere.” The camera pans over the glittering Bosphorus Strait as American ships glide silently through the passage connecting Asia and Europe.

Pakay’s film has long been almost impossible to see in the United States, aside from a short clip on YouTube. But in February, it began streaming on the Criterion Channel, and its reappearance is a useful occasion to re-examine one of the most important, and yet relatively unknown, aspects of Baldwin’s career: his time in Turkey.

More here.

An Enormous Gravity ‘Hum’ Moves Through the Universe

Jonathan O’Callaghan in Quanta:

The discovery, announced today, shows that extra-large ripples in space-time are constantly squashing and changing the shape of space. These gravitational waves are cousins to the echoes from black hole collisions first picked up by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) experiment in 2015. But whereas LIGO’s waves might vibrate a few hundred times a second, it might take years or decades for a single one of these gravitational waves to pass by at the speed of light.

The discovery, announced today, shows that extra-large ripples in space-time are constantly squashing and changing the shape of space. These gravitational waves are cousins to the echoes from black hole collisions first picked up by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) experiment in 2015. But whereas LIGO’s waves might vibrate a few hundred times a second, it might take years or decades for a single one of these gravitational waves to pass by at the speed of light.

The finding has opened a wholly new window on the universe, one that promises to reveal previously hidden phenomena such as the cosmic whirling of black holes that have the mass of billions of suns, or possibly even more exotic (and still hypothetical) celestial specters.

More here.

“Gödel, Escher, Bach” author Doug Hofstadter on the state of AI today

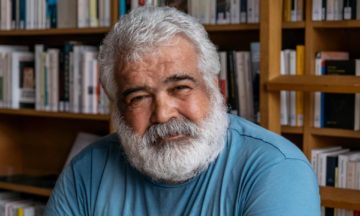

Khaled Khalifa: ‘All the places of my childhood are destroyed’

Michael Safi in The Guardian:

Khaled Khalifa is a Syrian novelist, poet and screenwriter whose work has been awarded the Naguib Mahfouz medal for literature, one of the Arab world’s highest literary honours. His soulful, often wry stories traverse time but are centred on the Syrian city of Aleppo, near where Khalifa was born in 1964, and once one of the world’s great cultural and trading hubs.

Khaled Khalifa is a Syrian novelist, poet and screenwriter whose work has been awarded the Naguib Mahfouz medal for literature, one of the Arab world’s highest literary honours. His soulful, often wry stories traverse time but are centred on the Syrian city of Aleppo, near where Khalifa was born in 1964, and once one of the world’s great cultural and trading hubs.

He studied and spent his early career in the city, but has lived in Damascus since 1999, one of the few writers who stayed throughout the country’s appalling civil war. He has tried to write about the Syrian capital, he said, but keeps finding himself drawn back to his home city. “After 50 pages, I felt it was not good writing,” he said. “I don’t know the fragrance of Damascus. So I turned back to Aleppo, and I accepted: OK, this is my place. I’ll write all my books about Aleppo. She is my city and resides deep in myself, in my soul.”

While Khalifa was writing his new book, No One Prayed Over Their Graves, Aleppo was comprehensively destroyed in fighting between the Syrian government and rebels. His work is banned in Syria.

More here.

Mughal-e-Azam: The Musical’s Prelude Screening At Times Square

People on Drugs Like Ozempic Say Their ‘Food Noise’ Has Disappeared

Dani Blum in The New York Times:

Until she started taking the weight loss drug Wegovy, Staci Klemmer’s days revolved around food. When she woke up, she plotted out what she would eat; as soon as she had lunch, she thought about dinner. After leaving work as a high school teacher in Bucks County, Pa., she would often drive to Taco Bell or McDonald’s to quell what she called a “24/7 chatter” in the back of her mind. Even when she was full, she wanted to eat. Almost immediately after Ms. Klemmer’s first dose of medication in February, she was hit with side effects: acid reflux, constipation, queasiness, fatigue. But, she said, it was like a switch flipped in her brain — the “food noise” went silent.

Until she started taking the weight loss drug Wegovy, Staci Klemmer’s days revolved around food. When she woke up, she plotted out what she would eat; as soon as she had lunch, she thought about dinner. After leaving work as a high school teacher in Bucks County, Pa., she would often drive to Taco Bell or McDonald’s to quell what she called a “24/7 chatter” in the back of her mind. Even when she was full, she wanted to eat. Almost immediately after Ms. Klemmer’s first dose of medication in February, she was hit with side effects: acid reflux, constipation, queasiness, fatigue. But, she said, it was like a switch flipped in her brain — the “food noise” went silent.

“I don’t think about tacos all the time anymore,” Ms. Klemmer, 57, said. “I don’t have cravings anymore. At all. It’s the weirdest thing.” Dr. Andrew Kraftson, a clinical associate professor at Michigan Medicine, said that over his 13 years as an obesity medicine specialist, people he treated would often say they couldn’t stop thinking about food. So when he started prescribing Wegovy and Ozempic, a diabetes medication that contains the same compound, and patients began to use the term food noise, saying it had disappeared, he knew exactly what they meant.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Reeling in a Skate on Kachemak Bay, Alaska

We drop bait and jig down eighteen fathoms,

trolling bottom for the halibut they say

are white and big as jib sails full of wind.

We drift this way all morning and I watch the men

pull up 30-pounders and sometimes

scaly Irish Lords, lustered as fool’s gold.

Drugged by the surprising warmth of this

eclipsed and argent Arctic light, I am amazed

when my line drags taut and in my hands

the heavy rod dips like a heron bends to drink.

I reel and reel, pulling up my own weight,

heavy as wet canvas. The men say to go slowly,

it will roll in fear and dive from foreign sun—

this fish has never seen the light. But who knows

what I’ve snagged from sodden sleep,

what blunt-eyed creature I haul out of darkness,

a ghostly harbinger that wavers toward me

like an insubstantial scrap of paper,

becoming larger as it nears. Too tired to resist

the last few feet it seems to help,

ascending easily, entranced by this bright world.

by Susan Elbe

—from Rattle #16, Winter 2001

Sunday, July 2, 2023

‘Why I might have done what I did’: conversations with Ireland’s most notorious murderer

Mark O’Connell in The Guardian:

Among Irish people old enough to remember the summer of 1982, Malcolm Macarthur is as close to a household name as it is possible for a murderer to be. He grew up in County Meath in the east of Ireland, on a grand estate with a housekeeper, a gardener and a governess. In his 20s, he received a large inheritance, and lived well on its bounty. But on the brink of middle age, he found he was going broke. At the time, the IRA was conducting a campaign of bank heists to fund their struggle. Macarthur was a clever and capable man, he reasoned, and so why should he not be able to pull off something along those lines?

Among Irish people old enough to remember the summer of 1982, Malcolm Macarthur is as close to a household name as it is possible for a murderer to be. He grew up in County Meath in the east of Ireland, on a grand estate with a housekeeper, a gardener and a governess. In his 20s, he received a large inheritance, and lived well on its bounty. But on the brink of middle age, he found he was going broke. At the time, the IRA was conducting a campaign of bank heists to fund their struggle. Macarthur was a clever and capable man, he reasoned, and so why should he not be able to pull off something along those lines?

He had been living for some months with a woman named Brenda Little and their son in Tenerife. He told Little that he had financial affairs to attend to, and flew to Dublin.

More here.

Most of the energy you put into a gasoline car is wasted; this is not the case for electric cars

Hannah Ritchie in Sustainability by Numbers:

For every dollar of petrol you put, you get just 20 cents’ worth of driving motion. The other 80 cents is wasted along the way – most of it as heat from the engine.

For every dollar of petrol you put, you get just 20 cents’ worth of driving motion. The other 80 cents is wasted along the way – most of it as heat from the engine.

Electric cars are much better at converting energy into motion. For every dollar of electricity you put in, you get 67 cents of driving motion plus another 22 cents of energy that’s recovered from regenerative braking. That means you get 89 cents’ worth out.

More here.

Two Ancestral Languages

Richard Dawkins at The Poetry of Reality:

The collective power endowed by language is captured in the legend of the Tower of Babel, where it threatened even God himself. “Go to,” God said, “Let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.” And lo, as a result of quasi-evolutionary divergence, we speak many thousands of mutually unintelligible tongues, the exact number undefined, mostly because dialect grades into language so we can’t decide where one language ends and the next begins. This smearing out is seen both across geographical space (think English worldwide) and through historical time as languages evolve through the centuries (try reading Chaucer). Nevertheless, because language is partly digital, chunked into the discrete semantic units that we call words, it is capable of great fidelity of transmission, especially in written forms. Yet, despite being thus capable, precious little verbal information from our dead ancestors filters down.

The collective power endowed by language is captured in the legend of the Tower of Babel, where it threatened even God himself. “Go to,” God said, “Let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.” And lo, as a result of quasi-evolutionary divergence, we speak many thousands of mutually unintelligible tongues, the exact number undefined, mostly because dialect grades into language so we can’t decide where one language ends and the next begins. This smearing out is seen both across geographical space (think English worldwide) and through historical time as languages evolve through the centuries (try reading Chaucer). Nevertheless, because language is partly digital, chunked into the discrete semantic units that we call words, it is capable of great fidelity of transmission, especially in written forms. Yet, despite being thus capable, precious little verbal information from our dead ancestors filters down.

But there is another language, also digital, of far greater precision and fidelity of transmission, which does preserve ancestral information, not through a paltry few generations but through hundreds of millions; a parallel language, which is not a human monopoly but is shared by all life: all animals, fungi, plants, bacteria, and archaea; a truly universal language that doesn’t suffer the confusion of dialect drift or trans-generational decay. Nor does it fall victim to the cumulative inflation of my opening fantasy, because it does not grow with each generation. As every schoolchild knows, acquired characteristics are not inherited. The genetic database changes, not cumulatively but by subtraction and addition approximately keeping pace with each other.

More here.

Burn Down the Admissions System

Yascha Mounk in Persuasion:

A few years ago, I listened to Jim Yong Kim, then the President of the World Bank, address the Milken Global Conference, a gathering that is about as plutocratic as it sounds. At the start of his remarks, Kim told the multimillionaires and billionaires who made up the bulk of the audience an anecdote, which he seemed to consider charming, about how he got his job.

A few years ago, I listened to Jim Yong Kim, then the President of the World Bank, address the Milken Global Conference, a gathering that is about as plutocratic as it sounds. At the start of his remarks, Kim told the multimillionaires and billionaires who made up the bulk of the audience an anecdote, which he seemed to consider charming, about how he got his job.

One day, while Kim was still in his previous job as the President of Dartmouth College, his assistant informed him of an unexpected phone call from Tim Geithner, the Secretary of the Treasury. Kim immediately reached for a pen. Naturally, he said, he expected that Geithner would ask for some nephew or family friend of his to get special consideration in the admissions process, and Kim wanted to be ready to jot down the applicant’s name. But to his astonishment, that wasn’t the case: Geithner was actually calling to see whether he might be interested in running the World Bank! (Cue appreciative chuckles from the audience.)

What was remarkable about this anecdote is just how normalized these forms of influence-peddling are in America’s elite.

More here.