Katrina Miller in The New York Times:

It’s often viewed as a given: Men hunted, women gathered. After all, the anthropological reasoning went, men were naturally more aggressive, whereas the slower pace of gathering was ideal for women, who were mainly focused on caretaking. “It’s not something I questioned,” said Sophia Chilczuk, a recent graduate of Seattle Pacific University, where she studied applied human biology. “And I think the majority of the public has that assumption.”

It’s often viewed as a given: Men hunted, women gathered. After all, the anthropological reasoning went, men were naturally more aggressive, whereas the slower pace of gathering was ideal for women, who were mainly focused on caretaking. “It’s not something I questioned,” said Sophia Chilczuk, a recent graduate of Seattle Pacific University, where she studied applied human biology. “And I think the majority of the public has that assumption.”

At times, the notion has proved stronger than the evidence at hand. In 1963, archaeologists in Colorado unearthed the nearly 10,000-year-old remains of a woman who had been buried with a projectile point. They concluded that the tool had been used not for killing game but, unconventionally, as a scraping knife.

But the male-centric narrative has been slowly changing. On the first day of a college anthropology course, Ms. Chilczuk and her classmates listened to a podcast about the landmark discovery of a female hunter during an excavation in Peru in 2018. Among fragments of cranium, teeth and leg bones, archaeologists found a hunting kit with more tools — projectile points, flakes, scrapers, choppers and burnishing stones — than they had ever seen. This discovery led the team to review the findings from other burials in the early Americas; in 2020 they concluded that big game hunting between 14,000 and 8,000 years ago was gender-neutral.

More here.

PATRICE RUNNER

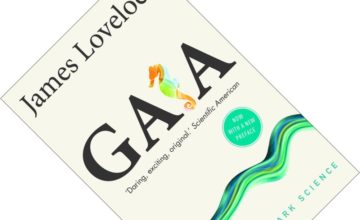

PATRICE RUNNER One year ago today, the famous scientist, environmentalist, and futurist James Lovelock passed away at the age of 103. Amongst his many achievements, he is best known for formulating the Gaia hypothesis: the notion that the Earth is a giant self-regulating system that maintains conditions suitable for life on the planet. I have always been somewhat suspicious of this idea but have simply never gotten around to properly reading up on it. High time to inform myself better and substantiate my so-far thinly-held opinion. Join me for a four-part series of book reviews in which I delve into Lovelock’s classic Gaia; his follow-up

One year ago today, the famous scientist, environmentalist, and futurist James Lovelock passed away at the age of 103. Amongst his many achievements, he is best known for formulating the Gaia hypothesis: the notion that the Earth is a giant self-regulating system that maintains conditions suitable for life on the planet. I have always been somewhat suspicious of this idea but have simply never gotten around to properly reading up on it. High time to inform myself better and substantiate my so-far thinly-held opinion. Join me for a four-part series of book reviews in which I delve into Lovelock’s classic Gaia; his follow-up  When one thinks of American pragmatism, one often puts too much emphasis on the American part. It might even stunt our enquiry, irrevocably fixating on thinkers such as John Dewey, William James, and Jane Addams. But there is more to the story of pragmatism than what happened in the United States around the turn of the

When one thinks of American pragmatism, one often puts too much emphasis on the American part. It might even stunt our enquiry, irrevocably fixating on thinkers such as John Dewey, William James, and Jane Addams. But there is more to the story of pragmatism than what happened in the United States around the turn of the  Susan Neiman: Well, I could also say that Woke Is Not Left. I wrote this book partly to figure out my own confusion. But it was a confusion that was reflected in conversations I have been having with friends in many different countries, all of whom, their whole lives, have stood on the side of the Left, and suddenly felt and said, “What is this? Maybe I’m not Left anymore.” And that struck me as wrong. But no one had quite teased out what the difference is and what the problems are. I didn’t want to give up the word “Left.” And I wanted to write a short book setting out what I consider to be left liberal principles as two different things and distinguishing them from the work in a nutshell. The very short thesis is that woke is fueled by traditional left-wing emotions, having your empathy for people who’ve been marginalized, wanting to correct historical discrimination and oppression. As you know, there’s a German saying that “your heart is on the left side of your body.” But the woke are undermined by what are actually very reactionary theoretical assumptions. And you do not have to have read Carl Schmitt or Michel Foucault in order to share those assumptions. Those assumptions have gotten into the water because every journalist went to college and picked up certain claims coming from these quite reactionary sources that are now often transmitted in the media as if they were self-evident truths. So, I wanted to show the gap between genuine left-wing philosophical assumptions and the premises that the woke are often acting on.

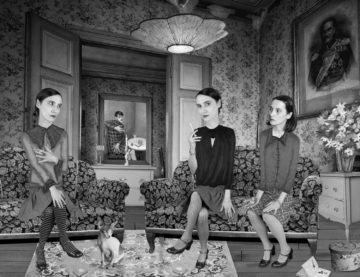

Susan Neiman: Well, I could also say that Woke Is Not Left. I wrote this book partly to figure out my own confusion. But it was a confusion that was reflected in conversations I have been having with friends in many different countries, all of whom, their whole lives, have stood on the side of the Left, and suddenly felt and said, “What is this? Maybe I’m not Left anymore.” And that struck me as wrong. But no one had quite teased out what the difference is and what the problems are. I didn’t want to give up the word “Left.” And I wanted to write a short book setting out what I consider to be left liberal principles as two different things and distinguishing them from the work in a nutshell. The very short thesis is that woke is fueled by traditional left-wing emotions, having your empathy for people who’ve been marginalized, wanting to correct historical discrimination and oppression. As you know, there’s a German saying that “your heart is on the left side of your body.” But the woke are undermined by what are actually very reactionary theoretical assumptions. And you do not have to have read Carl Schmitt or Michel Foucault in order to share those assumptions. Those assumptions have gotten into the water because every journalist went to college and picked up certain claims coming from these quite reactionary sources that are now often transmitted in the media as if they were self-evident truths. So, I wanted to show the gap between genuine left-wing philosophical assumptions and the premises that the woke are often acting on. This series of handmade photomontages was inspired by figurative master paintings created throughout art history—important moments in the western canon. My love for the particular presence of master paintings, combined with my own interest in photography, provided a starting point from which to explore. I then created reinventions—re-masterings—working through my personal sensitivity and engagements as an artist. Photomontage allows me to translate these paintings into new environments.

This series of handmade photomontages was inspired by figurative master paintings created throughout art history—important moments in the western canon. My love for the particular presence of master paintings, combined with my own interest in photography, provided a starting point from which to explore. I then created reinventions—re-masterings—working through my personal sensitivity and engagements as an artist. Photomontage allows me to translate these paintings into new environments. THERE IS, EASILY FOUND

THERE IS, EASILY FOUND Poornima Paidipaty interviews Pranab Bardhan in Phenomenal World:

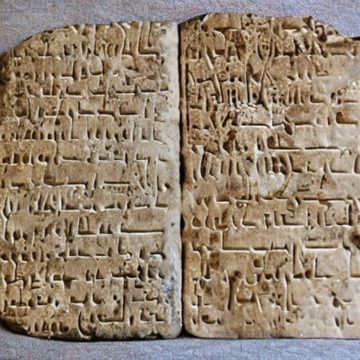

Poornima Paidipaty interviews Pranab Bardhan in Phenomenal World: Sophus Helle in Aeon:

Sophus Helle in Aeon: I

I In 1955 Henry Pleasants, a critic of both popular and classical music, issued a cranky screed of a book, “The Agony of Modern Music,” which opened with the implacable verdict that “serious music is a dead art.” Pleasants’s thesis was that the traditional forms of classical music — opera, oratorio, orchestral and chamber music, all constructions of a bygone era — no longer related to the experience of our modern lives. Composers had lost touch with the currents of popular taste, and popular music, with its vitality and its connection to the spirit of the times, had dethroned the classics. Absent the mass appeal enjoyed by past masters like Beethoven, Verdi, Wagner and Tchaikovsky, modern composers had retreated into obscurantism, condemned to a futile search for novelty amid the detritus of a tradition that was, like overworked soil, exhausted and fallow. One could still love classical music, but only with the awareness that it was a relic of the past and in no way representative of our contemporary experience.

In 1955 Henry Pleasants, a critic of both popular and classical music, issued a cranky screed of a book, “The Agony of Modern Music,” which opened with the implacable verdict that “serious music is a dead art.” Pleasants’s thesis was that the traditional forms of classical music — opera, oratorio, orchestral and chamber music, all constructions of a bygone era — no longer related to the experience of our modern lives. Composers had lost touch with the currents of popular taste, and popular music, with its vitality and its connection to the spirit of the times, had dethroned the classics. Absent the mass appeal enjoyed by past masters like Beethoven, Verdi, Wagner and Tchaikovsky, modern composers had retreated into obscurantism, condemned to a futile search for novelty amid the detritus of a tradition that was, like overworked soil, exhausted and fallow. One could still love classical music, but only with the awareness that it was a relic of the past and in no way representative of our contemporary experience.