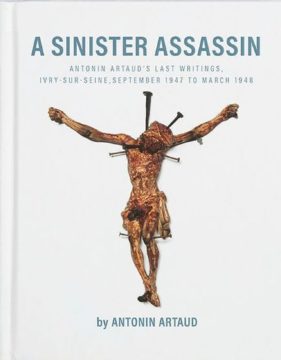

Jay Murphy at the LARB:

AT THE END of his life, the inveterate surrealist Antonin Artaud returned to his notion of a transformative “Theater of Cruelty.” In February 1948, a month before his death, in a famously banned radio broadcast in Paris entitled To Have Done with the Judgment of God, he proclaimed, “Man is ill because he is badly constructed,” announcing a “body without organs” that “will have delivered him from all his automatisms / and returned him to his true liberty.” Artaud saw this last radio work as a “mini-model” of what a Theater of Cruelty could be. Artaud had just emerged from a horrific, nine-year asylum confinement (lasting from September 1937 to May 1946), and the series of radio works were part of a ferocious taking back of his voice and life.

AT THE END of his life, the inveterate surrealist Antonin Artaud returned to his notion of a transformative “Theater of Cruelty.” In February 1948, a month before his death, in a famously banned radio broadcast in Paris entitled To Have Done with the Judgment of God, he proclaimed, “Man is ill because he is badly constructed,” announcing a “body without organs” that “will have delivered him from all his automatisms / and returned him to his true liberty.” Artaud saw this last radio work as a “mini-model” of what a Theater of Cruelty could be. Artaud had just emerged from a horrific, nine-year asylum confinement (lasting from September 1937 to May 1946), and the series of radio works were part of a ferocious taking back of his voice and life.

Artaud has primarily been known as a major collaborator with the Paris Surrealists (from 1925 to 1927), and avant-garde author of the extraordinarily eloquent if mysterious essays gathered in The Theatre and Its Double (1938), in which he very controversially called for a cataclysmic “Theater of Cruelty” that would replace centuries of representational “psychological” theater.

more here.

Tiny

Tiny  In a marked moment near the opening of Joyland—directed by Saim Sadiq and the first Pakistani film to be shortlisted by the Academy Awards—Haider meets Biba in a hospital in Lahore, looking dazed in a blood-splattered shirt. Though this is the first time they’ve met, we’re given no narration, just Haider’s wide-eyed, fascinated gaze. Later, in an intimate moment in her room, Biba tells Haider more about that night: about seeing her friend, also trans

In a marked moment near the opening of Joyland—directed by Saim Sadiq and the first Pakistani film to be shortlisted by the Academy Awards—Haider meets Biba in a hospital in Lahore, looking dazed in a blood-splattered shirt. Though this is the first time they’ve met, we’re given no narration, just Haider’s wide-eyed, fascinated gaze. Later, in an intimate moment in her room, Biba tells Haider more about that night: about seeing her friend, also trans Progress in the worlds of nutrition and everyday health has stalled, as has medicine to a more limited degree. We know a few things. You should exercise, avoid smoking, not be fat, and not jump off tall buildings. Besides that, there isn’t much we can tell you with certainty about what to eat and how to live your life.

Progress in the worlds of nutrition and everyday health has stalled, as has medicine to a more limited degree. We know a few things. You should exercise, avoid smoking, not be fat, and not jump off tall buildings. Besides that, there isn’t much we can tell you with certainty about what to eat and how to live your life. In the past 20 years, on economic measures, America has outperformed other rich countries. Over that period, median wages grew by 25%, compared with just 17% in Germany. Managers at Buc-ee’s, a Texas-based chain of stores, can make more than experienced doctors earn in Britain. But on a more fundamental measure of wellness—how long people live—America is falling behind. To its detractors, this is a cause for schadenfreude. “Many people say it is easier to buy a gun than baby formula in the us,” gloated a statement released by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs last year, which also pointed to declining life expectancy in general. In the past few years, according to some estimates, life expectancy in China overtook that in America. For Americans, that ought to be a more serious source of introspection than it is.

In the past 20 years, on economic measures, America has outperformed other rich countries. Over that period, median wages grew by 25%, compared with just 17% in Germany. Managers at Buc-ee’s, a Texas-based chain of stores, can make more than experienced doctors earn in Britain. But on a more fundamental measure of wellness—how long people live—America is falling behind. To its detractors, this is a cause for schadenfreude. “Many people say it is easier to buy a gun than baby formula in the us,” gloated a statement released by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs last year, which also pointed to declining life expectancy in general. In the past few years, according to some estimates, life expectancy in China overtook that in America. For Americans, that ought to be a more serious source of introspection than it is. In the introduction to Not Under Forty, Willa Cather’s 1936 collection of essays, she (in)famously writes that “the world broke in two in 1922 or thereabouts,” an opinion that, if nothing else, has fairly successfully separated her from the ranks of artists and authors we have come to call modernists.

In the introduction to Not Under Forty, Willa Cather’s 1936 collection of essays, she (in)famously writes that “the world broke in two in 1922 or thereabouts,” an opinion that, if nothing else, has fairly successfully separated her from the ranks of artists and authors we have come to call modernists.

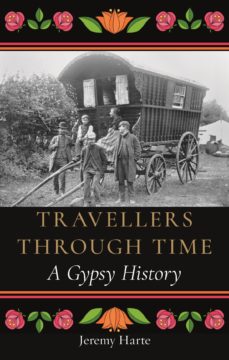

‘Roma’ and ‘Romani’ are words from the Romani language that have Indian etymologies – despite popular perceptions, they have no connection to Romania. People are commonly confused by the ordinariness of being Roma or part-Roma, and of seeming like ‘any old European’. It’s a confusion I and millions of others of Roma descent have dealt with all our lives. The reason for the confusion, as Europe and the Roma explains, is that six hundred years of cultural production have caused people to expect the opposite. The first four centuries following the earliest chronicled arrival of ‘Gypsies’ in Europe in about 1400 are covered by the opening third of the book. The remainder deals with the period since 1800. This lopsidedness of focus tells us something about the relative amounts of attention paid to Romani people by artists, writers and composers over time. Notwithstanding the subtler portrayals of Gypsies found, for instance, in the work of Emily Brontë and D H Lawrence, the tendency has been to use Gypsy characters as a kind of shorthand for savagery and nonconformity. When we read Prosper Mérimée’s appendix to his tale of Carmen, on which Bizet’s opera was based, we get a taste of this. ‘While they are still very young, their ugliness may not be unattractive,’ Mérimée wrote of Spanish Romani girls, ‘but once they have borne children they become positively repulsive.’

‘Roma’ and ‘Romani’ are words from the Romani language that have Indian etymologies – despite popular perceptions, they have no connection to Romania. People are commonly confused by the ordinariness of being Roma or part-Roma, and of seeming like ‘any old European’. It’s a confusion I and millions of others of Roma descent have dealt with all our lives. The reason for the confusion, as Europe and the Roma explains, is that six hundred years of cultural production have caused people to expect the opposite. The first four centuries following the earliest chronicled arrival of ‘Gypsies’ in Europe in about 1400 are covered by the opening third of the book. The remainder deals with the period since 1800. This lopsidedness of focus tells us something about the relative amounts of attention paid to Romani people by artists, writers and composers over time. Notwithstanding the subtler portrayals of Gypsies found, for instance, in the work of Emily Brontë and D H Lawrence, the tendency has been to use Gypsy characters as a kind of shorthand for savagery and nonconformity. When we read Prosper Mérimée’s appendix to his tale of Carmen, on which Bizet’s opera was based, we get a taste of this. ‘While they are still very young, their ugliness may not be unattractive,’ Mérimée wrote of Spanish Romani girls, ‘but once they have borne children they become positively repulsive.’ It’s rare to find a product so successful that its makers stop advertising it. But that’s what happened to the weight-loss drug Wegovy in May. In the United States, where prescription drugs can be advertised, developer Novo Nordisk pulled its television adverts because it couldn’t keep up with demand. The injectable medication, called semaglutide, works by imitating a hormone that curbs appetite and was approved as an obesity treatment by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2021. In a study, participants who took semaglutide for over a year lost more than twice as much body weight on average — almost 16% — as did people taking an older weight-loss drug that mimics the same hormone

It’s rare to find a product so successful that its makers stop advertising it. But that’s what happened to the weight-loss drug Wegovy in May. In the United States, where prescription drugs can be advertised, developer Novo Nordisk pulled its television adverts because it couldn’t keep up with demand. The injectable medication, called semaglutide, works by imitating a hormone that curbs appetite and was approved as an obesity treatment by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2021. In a study, participants who took semaglutide for over a year lost more than twice as much body weight on average — almost 16% — as did people taking an older weight-loss drug that mimics the same hormone

Call it AI’s man-behind-the-curtain effect: What appear at first to be dazzling new achievements in artificial intelligence routinely lose their luster and seem limited, one-off, jerry-rigged, with nothing all that impressive happening behind the scenes aside from sweat and tears, certainly nothing that deserves the name “intelligence” even by loose analogy.

Call it AI’s man-behind-the-curtain effect: What appear at first to be dazzling new achievements in artificial intelligence routinely lose their luster and seem limited, one-off, jerry-rigged, with nothing all that impressive happening behind the scenes aside from sweat and tears, certainly nothing that deserves the name “intelligence” even by loose analogy. One day early in the pandemic, when schools and colleges first went online, my undergraduate students and I had just finished discussing an essay on the rise and decline of the innovative and powerful Comanche empire. I logged off and walked downstairs, where my elementary school-aged child was sitting at the dining table. “What did you learn in school today?” I asked, as I always do. He recounted to me—not in these exact words, of course—that North America had been an Edenic paradise before the Europeans arrived. I was shocked. This was the racist myth of the noble savage repackaged by the antiracist left. In reality, Native Americans did not need Europeans to introduce them to warfare, imperialism, slavery, or violence. This does not diminish the significant impact European pathogens and ambitions had on Native American polities. But to teach such distortive myths about the past? That’s the kind of thing historians should be upset about.

One day early in the pandemic, when schools and colleges first went online, my undergraduate students and I had just finished discussing an essay on the rise and decline of the innovative and powerful Comanche empire. I logged off and walked downstairs, where my elementary school-aged child was sitting at the dining table. “What did you learn in school today?” I asked, as I always do. He recounted to me—not in these exact words, of course—that North America had been an Edenic paradise before the Europeans arrived. I was shocked. This was the racist myth of the noble savage repackaged by the antiracist left. In reality, Native Americans did not need Europeans to introduce them to warfare, imperialism, slavery, or violence. This does not diminish the significant impact European pathogens and ambitions had on Native American polities. But to teach such distortive myths about the past? That’s the kind of thing historians should be upset about. A honey bee’s life depends on it successfully harvesting nectar from flowers to make honey. Deciding which flower is most likely to offer nectar is incredibly difficult. Getting it right demands correctly weighing up subtle cues on flower type, age, and history—the best indicators a flower might contain a tiny drop of nectar. Getting it wrong is at best a waste of time, and at worst means exposure to a lethal predator hiding in the flowers. In new research

A honey bee’s life depends on it successfully harvesting nectar from flowers to make honey. Deciding which flower is most likely to offer nectar is incredibly difficult. Getting it right demands correctly weighing up subtle cues on flower type, age, and history—the best indicators a flower might contain a tiny drop of nectar. Getting it wrong is at best a waste of time, and at worst means exposure to a lethal predator hiding in the flowers. In new research