Category: Recommended Reading

Inanna/Ishtar

Emily H Wilson at The Guardian:

Inanna is remarkably little known these days, but at the dawn of civilisation, she was vastly important. She went on to become Ishtar, who is more widely recognised, and then aspects of her character were incorporated into the goddesses Aphrodite and Venus. Of all the deities, she is arguably the one who has lived the longest.

Inanna is remarkably little known these days, but at the dawn of civilisation, she was vastly important. She went on to become Ishtar, who is more widely recognised, and then aspects of her character were incorporated into the goddesses Aphrodite and Venus. Of all the deities, she is arguably the one who has lived the longest.

I first became interested in Inanna while rereading the Epic of Gilgamesh. She is something of a baddie in the story, throwing a massive sulk when Gilgamesh refuses to marry her. But what an interesting and unusual creature she is, even glimpsed sideways, in a story about the man who spurned her. Somehow, on earlier readings, I had failed to clock her magnificence.

It was then that I researched the myths in which Inanna is a central figure. There’s the story of her descent into the underworld, for example, which leads to her horrifying death and subsequent resurrection.

more here.

The Sea Captain Who Ran From Abraham Lincoln

Dorothy Wickenden at the New York Times:

Who was Appleton Oaksmith? One contemporary described him as a “good seaman, & a bold & daring officer.” His enemies, President Abraham Lincoln among them, judged him a scoundrel and a traitor. Oaksmith, writing six years after the Civil War, wasn’t sure what to think: “I look upon myself sometimes with a sort of doubt as to my own identity.”

Who was Appleton Oaksmith? One contemporary described him as a “good seaman, & a bold & daring officer.” His enemies, President Abraham Lincoln among them, judged him a scoundrel and a traitor. Oaksmith, writing six years after the Civil War, wasn’t sure what to think: “I look upon myself sometimes with a sort of doubt as to my own identity.”

Jonathan W. White, a prizewinning Civil War historian, finds in Oaksmith’s spectacularly misguided life both a gripping yarn set far from the battlefields and a way to dramatize Lincoln’s determination to eliminate the African slave trade.

As a young seafaring adventurer in the 1850s, Oaksmith armed mercenaries in Nicaragua and joined the liberation movement in Cuba. In 1859, he started a magazine, which foundered and left him bankrupt. As a Tammany Hall Democrat, he attempted to broker a misbegotten agreement between North and South. After Lincoln took office, in 1861, Oaksmith became a shipping agent, outfitting old whaling ships.

more here.

Uplifting Climate Change Good News — According To Al Gore

From GoodGoodGood.co:

Former U.S. Vice President Al Gore has been a huge player in the fight against climate change for as long as most of us can remember. As the founder and current chair of the Climate Reality Project, he has dedicated his life to climate action. And he says we have a lot to celebrate. Gore took the stage at the TED Countdown Summit in Detroit, Michigan this week to speak to the progress — and required action — in the climate movement.

Former U.S. Vice President Al Gore has been a huge player in the fight against climate change for as long as most of us can remember. As the founder and current chair of the Climate Reality Project, he has dedicated his life to climate action. And he says we have a lot to celebrate. Gore took the stage at the TED Countdown Summit in Detroit, Michigan this week to speak to the progress — and required action — in the climate movement.

…“The most important question these days is: How can we speed up solutions to the climate crisis? I’m convinced we are going to solve the climate crisis; we’ve got this,” Gore begins his talk. “The question remains: Will we solve it in time?” With a clock that seems to tick more rapidly (and loudly) than ever, Gore keeps us grounded in the truth: The climate crisis demands action — and we’re moving forward. “Obviously, the crisis has to be addressed,” he said. “The good news is… we are seeing tremendous progress.”

…As Gore reminds us, in August 2022, the United States passed the Inflation Reduction Act: A historic piece of legislation that will invest an estimated $1.2 trillion in climate action. The bill includes a variety of clean energy, climate mitigation and resilience, agriculture, and conservation-related programs and is the largest (and best!) federal climate policy the country has ever seen.

More here.

Helen of Troy Real—Not a Myth

Ruby Blondell in Lapham’s Quarterly:

Like her patron goddess, Venus, Helen of Troy represents, in Goethe’s famous phrase, the “eternal feminine.” She pervades the broader discourse of beauty culture in the early twentieth century. A newspaper article from 1916 informs us that an artist named Ray van Buren studied “the beauty of Helen as delineated in the finest Greek friezes and sculptures,” before extolling the modern women who, in his view, have “the same classic, tantalizing, heart-storming beauty as the immortal Helen of Troy.” A 1926 tip for lustrous hair (involving egg whites and carbolic acid) is attributed to Helen’s “beauty recipe books.” Her name appears less often than Venus’ in early movie titles, but advertisements for beauty products often invoke the goddess and her protégée in the same breath. Sometimes they are even conflated, as if Helen had been the winner—not just a bribe—at the Judgment of Paris: “The Search for a New Helen of Troy Begins in France, [with] the Modern Judgment of Paris…to Determine Who Is Most Beautiful.”

Like her patron goddess, Venus, Helen of Troy represents, in Goethe’s famous phrase, the “eternal feminine.” She pervades the broader discourse of beauty culture in the early twentieth century. A newspaper article from 1916 informs us that an artist named Ray van Buren studied “the beauty of Helen as delineated in the finest Greek friezes and sculptures,” before extolling the modern women who, in his view, have “the same classic, tantalizing, heart-storming beauty as the immortal Helen of Troy.” A 1926 tip for lustrous hair (involving egg whites and carbolic acid) is attributed to Helen’s “beauty recipe books.” Her name appears less often than Venus’ in early movie titles, but advertisements for beauty products often invoke the goddess and her protégée in the same breath. Sometimes they are even conflated, as if Helen had been the winner—not just a bribe—at the Judgment of Paris: “The Search for a New Helen of Troy Begins in France, [with] the Modern Judgment of Paris…to Determine Who Is Most Beautiful.”

As icons of female beauty, both Helen and her patron goddess were vehicles for contemporary ambivalence about the cultural legitimacy of modern America. Many sources opine that in Hollywood Helen would be nothing in comparison with the abundance of American beauties.

More here.

Friday, August 4, 2023

On poetry and mourning

Kamran Javadizadeh in The Yale Review:

Ninety-three days before she died, my sister sent me a message. Five and a half years earlier, Bita had been diagnosed with stage four intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, a rare and deadly form of cancer. She was forty-three. There was a thirteen-centimeter mass—roughly the size of a grapefruit—in her liver. When the radiologist friend who’d helped get Bita into Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center saw me in the hospital corridor after her diagnosis, he burst into tears.

Ninety-three days before she died, my sister sent me a message. Five and a half years earlier, Bita had been diagnosed with stage four intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, a rare and deadly form of cancer. She was forty-three. There was a thirteen-centimeter mass—roughly the size of a grapefruit—in her liver. When the radiologist friend who’d helped get Bita into Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center saw me in the hospital corridor after her diagnosis, he burst into tears.

Bita had been in treatment ever since; I had been beside her for nearly every appointment. They tended to be on Mondays: I’d take the train from Philadelphia to New York City and meet her in the waiting area of her oncologist’s clinic. Inside, I’d watch and listen and take notes. I discovered I had a talent for explaining to the doctor what my sister wanted to know but was reluctant to ask directly, and for explaining to Bita the implications of what he’d actually said rather than what she was afraid she’d heard. I’m a poetry critic and a teacher. What I did in the oncologist’s clinic was not so different from what I do in the classroom or on the page. I listened and redescribed what I’d heard; I connected threads, or tried to.

More here.

Global Boiling

Kate Mackenzie and Tim Sahay at Phenomenal World:

This July has been the hottest in our recorded history and, most likely, over the last 120,000 years. Four “Heat Domes” across the northern hemisphere—over West Asia, North America, North Africa and Southern Europe—contributed to soaring temperatures, not just breaking but shattering records by several degrees. High up in the Andes, winter has turned to a blazing summer. The sun has been blotted out by Canada’s enormous fires.

This July has been the hottest in our recorded history and, most likely, over the last 120,000 years. Four “Heat Domes” across the northern hemisphere—over West Asia, North America, North Africa and Southern Europe—contributed to soaring temperatures, not just breaking but shattering records by several degrees. High up in the Andes, winter has turned to a blazing summer. The sun has been blotted out by Canada’s enormous fires.

Together with deadly heat came unprecedented rains and flooding, most notably in Delhi and Beijing. It’s not just the carbon cycle but the water cycle that’s been supercharged by fossil-fueled modernity. We should never have called it Earth; ours is an oceanic planet, and most of the extra heat is being absorbed by oceans now hotter than ever before. Their warmed currents have meant that a Mexico-sized chunk of Antarctica failed to refreeze this year.

More here.

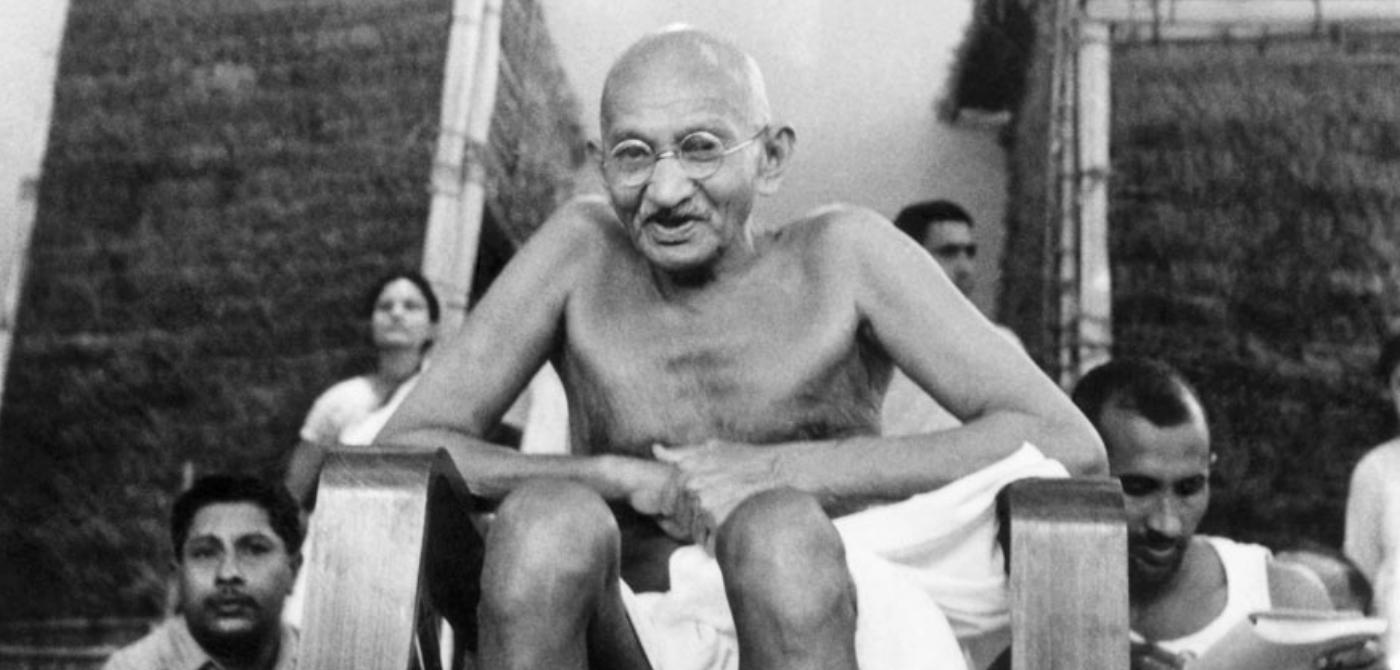

Gandhi and Liberal Modernity: The Vexed Question of Caste

Akeel Bilgrami in The India Forum:

I will begin on a self-conscious note. For some years, I have put off writing about Gandhi’s views on caste for my long-gestating book manuscript on Gandhi’s thought. The subject had become so fraught, as a result of recent invectives directed at Gandhi, that I did not trust myself to not get caught up in an ideological maelstrom in which anything one said by way of trying to merely even understand his views would come off as a kind of apologetics, which I had no wish to produce since, for all my admiring interest in him, I am not a Gandhi-bhakt. Indeed, as will emerge in what I am about to say, he is sometimes quite wrong on this subject as, no doubt, on others.

I will begin on a self-conscious note. For some years, I have put off writing about Gandhi’s views on caste for my long-gestating book manuscript on Gandhi’s thought. The subject had become so fraught, as a result of recent invectives directed at Gandhi, that I did not trust myself to not get caught up in an ideological maelstrom in which anything one said by way of trying to merely even understand his views would come off as a kind of apologetics, which I had no wish to produce since, for all my admiring interest in him, I am not a Gandhi-bhakt. Indeed, as will emerge in what I am about to say, he is sometimes quite wrong on this subject as, no doubt, on others.

What I am certain of, even so, is that his views on the subject and his motivations in forming them have not always been understood with the necessary depth. It is fine to find someone to be wrong, so long as you get right what you think is wrong. And it is with that in mind that I write this essay to present the larger framework within which, I think, his ideas about and his struggles over caste must be understood.

More here.

Slavoj Žižek & Sean Carroll: Quantum Physics, the Multiverse, and Time Travel

Who Was Duns Scotus?

Thomas M Ward at Aeon:

Scotus remains a polarising figure, but his humanist detractors would be horrified to learn that here in the 21st century we are witnessing a Scotus revival. Philosophers, theologians and intellectual historians are once again taking Scotus seriously, sometimes in a spirit of admiration and sometimes with passionate derision, but seriously nonetheless. Doubtless this is due in part to the progress of the International Scotistic Commission, which has in recent years completed critical editions of two of Scotus’s monumental works of philosophical theology: Ordinatio and Lectura. As these and other works have become more accessible, Scotus scholarship has boomed. According to the Scotus scholar Tobias Hoffmann, 20 per cent of all the Scotus scholarship produced over the past 70 years was produced in the past seven years. This explosion of interest in Scotus offers as good an occasion as any for introducing this brilliant and enigmatic thinker to a new audience.

Scotus remains a polarising figure, but his humanist detractors would be horrified to learn that here in the 21st century we are witnessing a Scotus revival. Philosophers, theologians and intellectual historians are once again taking Scotus seriously, sometimes in a spirit of admiration and sometimes with passionate derision, but seriously nonetheless. Doubtless this is due in part to the progress of the International Scotistic Commission, which has in recent years completed critical editions of two of Scotus’s monumental works of philosophical theology: Ordinatio and Lectura. As these and other works have become more accessible, Scotus scholarship has boomed. According to the Scotus scholar Tobias Hoffmann, 20 per cent of all the Scotus scholarship produced over the past 70 years was produced in the past seven years. This explosion of interest in Scotus offers as good an occasion as any for introducing this brilliant and enigmatic thinker to a new audience.

more here.

Friday Poem

As the Poems Go

as the poems go into the thousands you

realize that you’ve created very

little.

it comes down to the rain, the sunlight,

the traffic, the nights and the days of the

years, the faces.

leaving this will be easier than living

it, typing one more line now as

a man plays a piano through the radio,

the best writers have said very

little

and the worst,

far too much.

by Charles Bukowsky

from Poetic Outlaws

Lana Del Rey: A Great American Poet

Hannah Williams at The New Statesman:

In “The Song of Myself”, Whitman tells us “I am the man, I suffered, I was there”. The poetic force of his work, which the American poet James Wright terms his “delicacy”, arises from the exactness of his observations; Whitman’s dedication to what he called “every organ and attribute”. This commitment to specificity is vital in understanding Del Rey’s artistic evolution; in her work on NFR! and beyond, she exhibits an oblique approach to individual experience, one that places a similar emphasis on precision. An instinct for poetic specificity is most apparent on “Blue Bannisters”, “Kintsugi” and “Fingertips”, sprawling, stream-of-consciousness confessionals that speak to Jesus, her family, lovers past and present, the dead and the living and the unborn, America, the Earth and the heavens, herself. There’s a Whitman-esque delicacy to her lyrics, whether they’re about the way John Denver holds the note on “Rocky Mountain High”, her sister making birthday cake while chickens run around the yard, or dropping a location pin to her lover on a hot night in the canyon.

In “The Song of Myself”, Whitman tells us “I am the man, I suffered, I was there”. The poetic force of his work, which the American poet James Wright terms his “delicacy”, arises from the exactness of his observations; Whitman’s dedication to what he called “every organ and attribute”. This commitment to specificity is vital in understanding Del Rey’s artistic evolution; in her work on NFR! and beyond, she exhibits an oblique approach to individual experience, one that places a similar emphasis on precision. An instinct for poetic specificity is most apparent on “Blue Bannisters”, “Kintsugi” and “Fingertips”, sprawling, stream-of-consciousness confessionals that speak to Jesus, her family, lovers past and present, the dead and the living and the unborn, America, the Earth and the heavens, herself. There’s a Whitman-esque delicacy to her lyrics, whether they’re about the way John Denver holds the note on “Rocky Mountain High”, her sister making birthday cake while chickens run around the yard, or dropping a location pin to her lover on a hot night in the canyon.

more here.

Lana Del Rey – Did You Know That There’s A Tunnel Under Ocean Blvd

Welcome to the Zombie Election

Christina Cauterucci in Slate:

The 2024 presidential election is 14 months away, which means political news sites are already saturated with poll-obsessed prognostication and horse-race reporting. In this way, every election season is alike—but this year’s run-up has felt particularly repetitive. Joe Biden, who reportedly told advisers in 2019 that he would not seek a second term if elected in 2020, is seeking a second term. Donald Trump, a former president enthusiastically campaigning in the shadow of multiple indictments, is all but certain to be the Republican nominee. The 2024 race is turning out to be a zombie contest: It’s November 2020, risen from the dead, with an abundance of ugly new boils to flaunt.

The 2024 presidential election is 14 months away, which means political news sites are already saturated with poll-obsessed prognostication and horse-race reporting. In this way, every election season is alike—but this year’s run-up has felt particularly repetitive. Joe Biden, who reportedly told advisers in 2019 that he would not seek a second term if elected in 2020, is seeking a second term. Donald Trump, a former president enthusiastically campaigning in the shadow of multiple indictments, is all but certain to be the Republican nominee. The 2024 race is turning out to be a zombie contest: It’s November 2020, risen from the dead, with an abundance of ugly new boils to flaunt.

The country isn’t too happy about it. A recent CNN poll of registered voters found that 31 percent viewed neither Biden nor Trump favorably. Compare that to the 19 percent who viewed neither Hillary Clinton nor Trump favorably just before the 2016 election. That was already the only election in recorded history in which more Americans disliked the two major party candidates than liked them. Voters have spent a cumulative seven years watching Trump and Biden perform the job of president, and about a third of them haven’t liked what they’ve seen.

More here.

How Old Can Humans Get?

Bill Gifford in Scientific American:

How long can human beings live? Although life expectancy has increased significantly over the past century, thanks largely to improved sanitation and medicine, research into hunter-gatherer populations suggests that individuals who escaped disease and violent deaths could live to about their seventh or eighth decade. This means our typical human life span may be static: around 70 years, with an extra decade or so for advanced medical care and cautious behavior. Some geneticists believe a hard limit of of around 115 years is essentially programmed into our genome by evolution. Other scientists in the fast-moving field of aging research, or geroscience, think we can live much longer. A handful of compounds have been shown to lengthen the life spans of laboratory animals slightly, yet some scientists are more ambitious—a lot more ambitious.

How long can human beings live? Although life expectancy has increased significantly over the past century, thanks largely to improved sanitation and medicine, research into hunter-gatherer populations suggests that individuals who escaped disease and violent deaths could live to about their seventh or eighth decade. This means our typical human life span may be static: around 70 years, with an extra decade or so for advanced medical care and cautious behavior. Some geneticists believe a hard limit of of around 115 years is essentially programmed into our genome by evolution. Other scientists in the fast-moving field of aging research, or geroscience, think we can live much longer. A handful of compounds have been shown to lengthen the life spans of laboratory animals slightly, yet some scientists are more ambitious—a lot more ambitious.

João Pedro de Magalhães, a professor of molecular biogerontology at the Institute of Inflammation and Ageing at the University of Birmingham in England, thinks humans could live for 1,000 years. He has scrutinized the genomes of very long-lived animals such as the bowhead whale (which can reach 200 years) and the naked mole rat. His surprising conclusion: if we eliminated aging at the cellular level, humans could live for a millennium—and potentially as long as 20,000 years.

More here.

Thursday, August 3, 2023

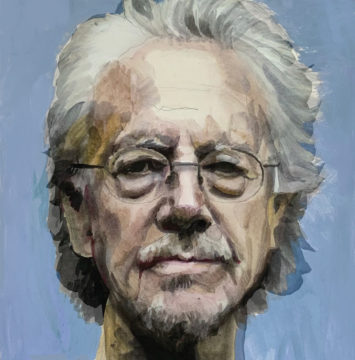

What happened to Peter Handke?

David Schurman Wallace in The Nation:

Although Handke first came to prominence as a playwright and novelist of prolific output (he’s the author of dozens of works), he has become much better known for his politics. His support for Serbia in the Balkan Wars of the 1990s, particularly his statements about the genocidal violence committed against Bosnian Muslims, has made him a pariah. A habitual contrarian, Handke embraced his outcast status and offered a bizarre disputation of the facts of the war that struck many as delusional, especially considering that he had only a glancing personal interest in Balkan politics—his mother was Slovenian, a fact he clung to with increasing intensity. In the years that followed, Handke has dug in even deeper. When Slobodan Milošević died in 2006 during his trial for war crimes, Handke spoke at his funeral. Years later, he was feted and decorated by the Serbian government. Despite the support of high-profile writers like Elfriede Jelinek and Karl Ove Knausgaard, his reputation has suffered. When he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2019, protest was widespread and one member of the Nobel committee promptly resigned, in part because of his politics.

Although Handke first came to prominence as a playwright and novelist of prolific output (he’s the author of dozens of works), he has become much better known for his politics. His support for Serbia in the Balkan Wars of the 1990s, particularly his statements about the genocidal violence committed against Bosnian Muslims, has made him a pariah. A habitual contrarian, Handke embraced his outcast status and offered a bizarre disputation of the facts of the war that struck many as delusional, especially considering that he had only a glancing personal interest in Balkan politics—his mother was Slovenian, a fact he clung to with increasing intensity. In the years that followed, Handke has dug in even deeper. When Slobodan Milošević died in 2006 during his trial for war crimes, Handke spoke at his funeral. Years later, he was feted and decorated by the Serbian government. Despite the support of high-profile writers like Elfriede Jelinek and Karl Ove Knausgaard, his reputation has suffered. When he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2019, protest was widespread and one member of the Nobel committee promptly resigned, in part because of his politics.

More here.

A jargon-free explanation of how AI large language models work

Timothy B. Lee and Sean Trott in Ars Technica:

The goal of this article is to make a lot of this knowledge accessible to a broad audience. We’ll aim to explain what’s known about the inner workings of these models without resorting to technical jargon or advanced math.

The goal of this article is to make a lot of this knowledge accessible to a broad audience. We’ll aim to explain what’s known about the inner workings of these models without resorting to technical jargon or advanced math.

We’ll start by explaining word vectors, the surprising way language models represent and reason about language. Then we’ll dive deep into the transformer, the basic building block for systems like ChatGPT. Finally, we’ll explain how these models are trained and explore why good performance requires such phenomenally large quantities of data.

To understand how language models work, you first need to understand how they represent words. Humans represent English words with a sequence of letters, like C-A-T for “cat.” Language models use a long list of numbers called a “word vector.”

More here.

How To Overhaul Higher Education

William Deresiewicz in Persuasion:

Let’s get a few things straight to start with. First, higher education as it currently exists is not going anywhere. There are more than 3700 colleges and universities in this country, with a total enrollment of 19 million, and they aren’t going to suddenly disappear. Or even gradually disappear. Since around 2013, with the advent of online instruction, people have been predicting that half of American colleges and universities would be gone within 10-15 years (it’s always 10-15 years, no matter when the prediction is made). Over the same period, the number of four-year institutions, not counting for-profits (which deserve to die), has actually gone up.

Let’s get a few things straight to start with. First, higher education as it currently exists is not going anywhere. There are more than 3700 colleges and universities in this country, with a total enrollment of 19 million, and they aren’t going to suddenly disappear. Or even gradually disappear. Since around 2013, with the advent of online instruction, people have been predicting that half of American colleges and universities would be gone within 10-15 years (it’s always 10-15 years, no matter when the prediction is made). Over the same period, the number of four-year institutions, not counting for-profits (which deserve to die), has actually gone up.

Second, higher education should not disappear. Colleges and universities serve essential functions that are not conceivably replicable without them. Higher ed is not dysfunctional, at least not in the strict sense of the word. It still functions. Students learn; experts and professionals are trained; knowledge is created. Get your appendix removed by someone without an MD, and then we can talk. There are 463 research universities in the United States. If they ceased to exist, where would the work they do be carried out? Your garage?

More here.

Matt Taibbi: How the Left lost its mind

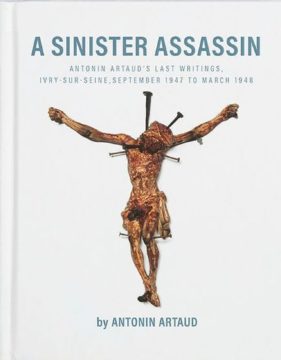

Artaud’s Final Testaments

Jay Murphy at the LARB:

AT THE END of his life, the inveterate surrealist Antonin Artaud returned to his notion of a transformative “Theater of Cruelty.” In February 1948, a month before his death, in a famously banned radio broadcast in Paris entitled To Have Done with the Judgment of God, he proclaimed, “Man is ill because he is badly constructed,” announcing a “body without organs” that “will have delivered him from all his automatisms / and returned him to his true liberty.” Artaud saw this last radio work as a “mini-model” of what a Theater of Cruelty could be. Artaud had just emerged from a horrific, nine-year asylum confinement (lasting from September 1937 to May 1946), and the series of radio works were part of a ferocious taking back of his voice and life.

AT THE END of his life, the inveterate surrealist Antonin Artaud returned to his notion of a transformative “Theater of Cruelty.” In February 1948, a month before his death, in a famously banned radio broadcast in Paris entitled To Have Done with the Judgment of God, he proclaimed, “Man is ill because he is badly constructed,” announcing a “body without organs” that “will have delivered him from all his automatisms / and returned him to his true liberty.” Artaud saw this last radio work as a “mini-model” of what a Theater of Cruelty could be. Artaud had just emerged from a horrific, nine-year asylum confinement (lasting from September 1937 to May 1946), and the series of radio works were part of a ferocious taking back of his voice and life.

Artaud has primarily been known as a major collaborator with the Paris Surrealists (from 1925 to 1927), and avant-garde author of the extraordinarily eloquent if mysterious essays gathered in The Theatre and Its Double (1938), in which he very controversially called for a cataclysmic “Theater of Cruelty” that would replace centuries of representational “psychological” theater.

more here.