Carl Zimmer in The New York Times:

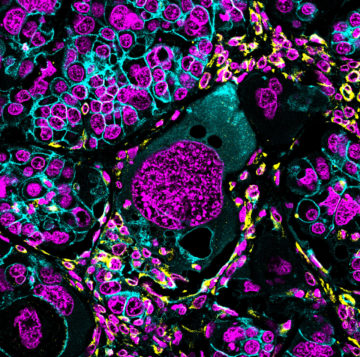

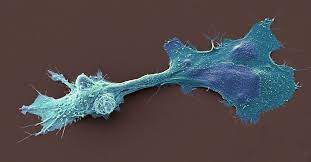

Over the past few years, a flurry of studies have found that tumors harbor a remarkably rich array of bacteria, fungi and viruses. These surprising findings have led many scientists to rethink the nature of cancer. The medical possibilities were exciting: If tumors shed their distinctive microbes into the bloodstream, could they serve as an early marker of the disease? Or could antibiotics even shrink tumors? In 2019, a start-up dug into these findings to develop microbe-based tests for cancer. This year, regulators agreed to prioritize an upcoming trial of the company’s test because of its promise for saving lives. But now several research teams have cast doubt on three of the most prominent studies in the field, reporting that they were unable to reproduce the results. The purported tumor microbes, the critics said, were most likely mirages or the result of contamination.

Over the past few years, a flurry of studies have found that tumors harbor a remarkably rich array of bacteria, fungi and viruses. These surprising findings have led many scientists to rethink the nature of cancer. The medical possibilities were exciting: If tumors shed their distinctive microbes into the bloodstream, could they serve as an early marker of the disease? Or could antibiotics even shrink tumors? In 2019, a start-up dug into these findings to develop microbe-based tests for cancer. This year, regulators agreed to prioritize an upcoming trial of the company’s test because of its promise for saving lives. But now several research teams have cast doubt on three of the most prominent studies in the field, reporting that they were unable to reproduce the results. The purported tumor microbes, the critics said, were most likely mirages or the result of contamination.

“They just found stuff that wasn’t there,” said Steven Salzberg, an expert on analyzing DNA sequences at Johns Hopkins University, who published one of the recent critiques. The authors of the work defended their data and pointed to more recent studies that reached similar conclusions. The unfolding debate reveals the tension between the potentially powerful applications that may come from understanding tumor microbes, and the challenge of deciphering their true nature. Independent experts said the current controversy is an example of the growing pains of a young but promising field. Biologists have known for decades that at least some microbes play a part in cancer. The most striking example is a virus known as HPV, which causes cervical cancer by infecting cells. And certain strains of bacteria drive other cancers in organs such as the intestines and the stomach.

More here.

Italy would be where I would whisk, mix, and knead my way into an idealized self. If I could get there, I would shed my anxious energy and compulsive need for affirmation, my nasty addiction to the cool-mint vape. I would slow down; I would journal. I would become tan and strong from simple pastas. I would eat intuitively — no more take-out burritos in the middle of the night, no more nubby cheeses scrounged from the bowels of the fridge. If I could find a way to go to Italy, I would become a real baker.

Italy would be where I would whisk, mix, and knead my way into an idealized self. If I could get there, I would shed my anxious energy and compulsive need for affirmation, my nasty addiction to the cool-mint vape. I would slow down; I would journal. I would become tan and strong from simple pastas. I would eat intuitively — no more take-out burritos in the middle of the night, no more nubby cheeses scrounged from the bowels of the fridge. If I could find a way to go to Italy, I would become a real baker. One day, while threading a needle to sew a button, I noticed that my tongue was sticking out. The same thing happened later, as I carefully cut out a photograph. Then another day, as I perched precariously on a ladder painting the window frame of my house, there it was again!

One day, while threading a needle to sew a button, I noticed that my tongue was sticking out. The same thing happened later, as I carefully cut out a photograph. Then another day, as I perched precariously on a ladder painting the window frame of my house, there it was again! Smith was not only a great thinker but also a great writer. He was an empirical economist whose sketchy data were

Smith was not only a great thinker but also a great writer. He was an empirical economist whose sketchy data were  Halfway through my interview with the co-founder of

Halfway through my interview with the co-founder of  The Coming Wave distils what is about to happen in a forcefully clear way. AI, Suleyman argues, will rapidly reduce the price of achieving any goal. Its astonishing labour-saving and problem-solving capabilities will be available cheaply and to anyone who wants to use them. He memorably calls this “the plummeting cost of power”. If the printing press allowed ordinary people to own books, and the silicon chip put a computer in every home, AI will democratise simply doing things. So, sure, that means getting a virtual assistant to set up a company for you, or using a swarm of builder bots to throw up an extension. Unfortunately, it also means engineering a run on a bank, or creating a deadly virus using a DNA synthesiser.

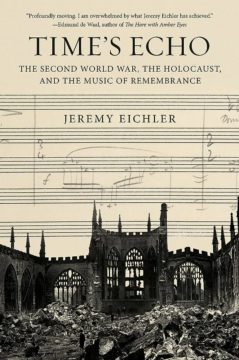

The Coming Wave distils what is about to happen in a forcefully clear way. AI, Suleyman argues, will rapidly reduce the price of achieving any goal. Its astonishing labour-saving and problem-solving capabilities will be available cheaply and to anyone who wants to use them. He memorably calls this “the plummeting cost of power”. If the printing press allowed ordinary people to own books, and the silicon chip put a computer in every home, AI will democratise simply doing things. So, sure, that means getting a virtual assistant to set up a company for you, or using a swarm of builder bots to throw up an extension. Unfortunately, it also means engineering a run on a bank, or creating a deadly virus using a DNA synthesiser. In 1947, the Black German musician Fasia Jansen stood on a street in Hamburg and began to sing the music of Brecht in her thick Low German accent to anyone passing by. Perhaps she’d learned the songs from prisoners and internees at Neuengamme, the concentration camp where she’d been forced to work four years earlier. Perhaps she’d learned them in the early days after the war, when she’d performed with Holocaust survivors at a hospital in 1945. One thing was clear: As Jansen wrestled with her trauma, song was at the center of her experience.

In 1947, the Black German musician Fasia Jansen stood on a street in Hamburg and began to sing the music of Brecht in her thick Low German accent to anyone passing by. Perhaps she’d learned the songs from prisoners and internees at Neuengamme, the concentration camp where she’d been forced to work four years earlier. Perhaps she’d learned them in the early days after the war, when she’d performed with Holocaust survivors at a hospital in 1945. One thing was clear: As Jansen wrestled with her trauma, song was at the center of her experience. Herman Mark Schwartz in The Syllabus:

Herman Mark Schwartz in The Syllabus: Samuel Moyn in Boston Review:

Samuel Moyn in Boston Review: