J.M. Tyree at Bennington Review:

The previous week, I’d traveled with two of these American friends, both philosophers, Steven and Morgan, from Berlin to Hamburg to Lübeck because, again, why not. We ate chicken tikka on jacket potatoes at outdoor tables overlooking the warehouses near the city gates used as the abandoned building where Nosferatu lives in Murnau’s classic 1922 film. Just as I’d lined up my shot in my best imitation Expressionist light, with the setting sun pouring through a keyhole shape in the building, a paddle-boarder glided into the frame to ruin the picture, a 10/10 German prank on a film location tourist.

The previous week, I’d traveled with two of these American friends, both philosophers, Steven and Morgan, from Berlin to Hamburg to Lübeck because, again, why not. We ate chicken tikka on jacket potatoes at outdoor tables overlooking the warehouses near the city gates used as the abandoned building where Nosferatu lives in Murnau’s classic 1922 film. Just as I’d lined up my shot in my best imitation Expressionist light, with the setting sun pouring through a keyhole shape in the building, a paddle-boarder glided into the frame to ruin the picture, a 10/10 German prank on a film location tourist.

Never go on holiday with two philosophers, especially if one is a Hegelian. The dialectical reversals about where to get breakfast will make your head spin. Only the tour of the port container in Hamburg finally shut them up—global capitalism is infinitely complex and would continue to run on its own without us for a very long time. All kidding aside, these are lovely old friends, especially when they aren’t reminding you constantly that arts profs like me learn next to nothing about the history of aesthetic theory in the course of their education.

more here.

Watching a video of Sebald, at his desk, surveying his photographs with magnifying glass in hand, it is tempting to interpret his work—the prose fiction, the poetry, the essays—as existing, prior to the texts, as an assemblage of pictures. One imagines a pristine terrain of images being dissolved into the current of language, each photograph gradually written away until only the most unyielding ones remain. The jumble of photographs and manuscript pages obscuring and framing each other in the television image of Sebald’s desk are reflected in a similar mixed spatial and temporal aggregation on the printed page, where the whole is defined as much by overlapping and masking as by juxtaposition. Sometimes the edges of the photographs cause shadows to fall on the text and vice versa. Windows and lighthouses, doorways and gravestones: sometimes, the images protrude from the temporal plane of the writing (the time of the narrative); sometimes, they are visible from below the surface. The interruption of reading performed by the images confirms the irregular chronological dynamic of Sebald’s work. Constantly hindered, sent back into countless eddies and still backwaters, time, like the mineral water that is sieved through the salt frames of Bad Kissingen, percolates as much as it flows.

Watching a video of Sebald, at his desk, surveying his photographs with magnifying glass in hand, it is tempting to interpret his work—the prose fiction, the poetry, the essays—as existing, prior to the texts, as an assemblage of pictures. One imagines a pristine terrain of images being dissolved into the current of language, each photograph gradually written away until only the most unyielding ones remain. The jumble of photographs and manuscript pages obscuring and framing each other in the television image of Sebald’s desk are reflected in a similar mixed spatial and temporal aggregation on the printed page, where the whole is defined as much by overlapping and masking as by juxtaposition. Sometimes the edges of the photographs cause shadows to fall on the text and vice versa. Windows and lighthouses, doorways and gravestones: sometimes, the images protrude from the temporal plane of the writing (the time of the narrative); sometimes, they are visible from below the surface. The interruption of reading performed by the images confirms the irregular chronological dynamic of Sebald’s work. Constantly hindered, sent back into countless eddies and still backwaters, time, like the mineral water that is sieved through the salt frames of Bad Kissingen, percolates as much as it flows. Whether we’re living in the age of

Whether we’re living in the age of  Graça Raposo was a young postdoc in the Netherlands in 1996 when she discovered that cells in her laboratory were sending secret messages to each other. She was exploring how immune cells react to foreign molecules. Using electron microscopy, she saw how cells ingested these molecules, which became stuck to the surface of tiny intracellular vesicles. The cells then spat out the vesicles, along with the foreign cargo, and Raposo captured them. Next, she presented them to another type of immune cell. It reacted to the package just as it would to a foreign molecule

Graça Raposo was a young postdoc in the Netherlands in 1996 when she discovered that cells in her laboratory were sending secret messages to each other. She was exploring how immune cells react to foreign molecules. Using electron microscopy, she saw how cells ingested these molecules, which became stuck to the surface of tiny intracellular vesicles. The cells then spat out the vesicles, along with the foreign cargo, and Raposo captured them. Next, she presented them to another type of immune cell. It reacted to the package just as it would to a foreign molecule As James Grammer, the president of the

As James Grammer, the president of the  Would you live in a building, cross a bridge, or trust a dam wall if there were a 10 percent chance of it collapsing? Or 5 percent? Or 1 percent? Of course not! In civil engineering, acceptable probabilities of failure generally range from 1-in-10,000 to 1-in-10-million.

Would you live in a building, cross a bridge, or trust a dam wall if there were a 10 percent chance of it collapsing? Or 5 percent? Or 1 percent? Of course not! In civil engineering, acceptable probabilities of failure generally range from 1-in-10,000 to 1-in-10-million. The Republican Party’s primary season officially gets underway four months from today, on January 15, 2024, the day the Iowa caucuses are held. That makes this a fitting moment to take stock of where things stand—and to reflect on the most astonishing and disturbing fact of America’s political present, which is that, short of a medical event that requires him to bow out of the race, the twice-impeached, serially indicted former president Donald Trump, who has led the field by a wide margin for over a year and is currently ahead by

The Republican Party’s primary season officially gets underway four months from today, on January 15, 2024, the day the Iowa caucuses are held. That makes this a fitting moment to take stock of where things stand—and to reflect on the most astonishing and disturbing fact of America’s political present, which is that, short of a medical event that requires him to bow out of the race, the twice-impeached, serially indicted former president Donald Trump, who has led the field by a wide margin for over a year and is currently ahead by  A

A I walk to and from my office daily. It takes 25 minutes, if you don’t stop at all to look at your phone. (It takes me 35 to 40.) That includes a few steep hills, of the kind I didn’t believe existed in Ohio before I moved here. (

I walk to and from my office daily. It takes 25 minutes, if you don’t stop at all to look at your phone. (It takes me 35 to 40.) That includes a few steep hills, of the kind I didn’t believe existed in Ohio before I moved here. ( Every day is not easy,” says Jill Duggar Dillard, “and right now is one of those seasons.” As a member of one of reality television’s most familiar and unquestionably largest families, the fourth Duggar child spent her formative years playing the role she most wanted to fill, the “good girl,” the “Sweet Jilly Muffin.” But then she married and began to assert her adult independence. And then the revelations about

Every day is not easy,” says Jill Duggar Dillard, “and right now is one of those seasons.” As a member of one of reality television’s most familiar and unquestionably largest families, the fourth Duggar child spent her formative years playing the role she most wanted to fill, the “good girl,” the “Sweet Jilly Muffin.” But then she married and began to assert her adult independence. And then the revelations about  Toby Green in Compact:

Toby Green in Compact: David Klion in The Baffler:

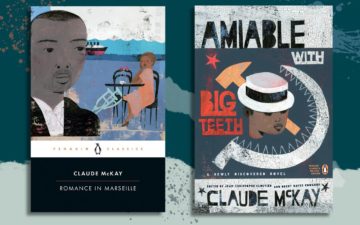

David Klion in The Baffler: Gary Edward Holcomb in LA Review of Books:

Gary Edward Holcomb in LA Review of Books: