Gary Edward Holcomb in LA Review of Books:

Gary Edward Holcomb in LA Review of Books:

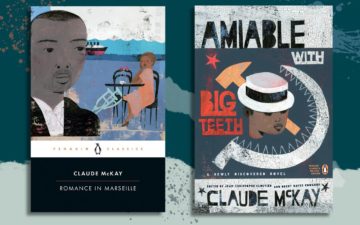

IN THE SUMMER of 1929, Claude McKay related to his close friend, the eminent bohemian Louise Bryant, an anecdote about a late night of revelry in the Paris studio of John Glassco and Graeme Taylor, two young, out expat Canadians.* McKay’s letter recounts that he proposed to the gathering a “nice bi-sexual party.” Clearly enjoying himself, he then says that his suggestion offended one of the roisterers, who snapped, “You know, Claude, you have a reputation for being a homo.” The Harlem Renaissance author’s retort would draw on Gertrude “Ma” Rainey’s defiantly lesbian tune, “Prove It on Me Blues,” released a year earlier. To the offended partier, McKay responded, “Sure … I sleep with all the boys, but only the aristocratic ones, and so it’s hard to prove anything on me.”

As well as McKay’s correspondence, his poetry expresses gay love, his fiction brims with queer content, and his memoirs speak directly about his homosexuality. The record of McKay’s divergent sex life, however, isn’t limited to the Jamaican author’s own writings. “Buffy” Glassco’s 1970 Memoirs of Montparnasse gives McKay, one of the white memoirist’s many gay lovers, the queer-coded name “Jack Relief.” Up against such oppressive ideological apparatuses as the Comstock laws, queer Harlem Renaissance writers were compelled to be chary about exposing their private lives.

More here.