Jackson Arn at The New Yorker:

The Lippis raise an important point, which “Manet/Degas” can’t help circling back to: great painters are not necessarily good painters. Art lovers, probably overcorrecting for “my kid could do that” philistinism, can be touchy about this, but in the case of Manet, a painter as great as he was technically dubious, it can’t be said too often. In much of his early work, near and far bump against each other—the rainbow in “Fishing” (ca. 1862-63) is as phony as the backdrop for a middle-school play—and his figures never really seem to be standing on solid ground, as though he’s cut them out of someone else’s painting. In the eighteen-sixties, Manet cut out a significant chunk of his own painting, “Episode from a Bullfight,” in response to criticism that he’d botched the perspective. It’s the kind of story you rarely find in art mythology: avant-gardists are supposed to be indifferent to critics, deliberate in their desecrations of tradition. In the case of Manet, the celebrated ur-modernist who made the world safe for flat, unfinished-looking art, it’s extra startling. Surely he, of all people, understood what he’d done.

more here.

‘That’s our mountain,’ a wordy Neapolitan told Hester Piozzi, ‘which throws up money for us, by calling foreigners to see the extraordinary effects of so surprising a phenomenon.’ The hermits were only one part of a flourishing and lucrative Vesuvius service industry that visitors encountered as they began their ascents. As Brewer says, what the industry was ‘selling was a sublime experience’. Making your own way up the mountain to see the extraordinary effects was perilous, but help was at hand. Your first encounter upon arrival would be with a disorganised horde of vociferous guides, all offering their services. The spectacle seems to have been distinctly off-putting: the poet Shelley, generally a friend of humanity, thought these particular humans ‘degraded, disgusting & odious’. Degraded or not, some guides became celebrities: Salvatore Madonna (‘il capo cicerone’) was well-known for his narrative skills and general charm, as well as for his knowledge of the territory, and he even appeared in guidebooks as a colourful feature of the scene to be looked out for. Madonna seems to have been a professional type, but untrustworthy guides were not uncommon.

‘That’s our mountain,’ a wordy Neapolitan told Hester Piozzi, ‘which throws up money for us, by calling foreigners to see the extraordinary effects of so surprising a phenomenon.’ The hermits were only one part of a flourishing and lucrative Vesuvius service industry that visitors encountered as they began their ascents. As Brewer says, what the industry was ‘selling was a sublime experience’. Making your own way up the mountain to see the extraordinary effects was perilous, but help was at hand. Your first encounter upon arrival would be with a disorganised horde of vociferous guides, all offering their services. The spectacle seems to have been distinctly off-putting: the poet Shelley, generally a friend of humanity, thought these particular humans ‘degraded, disgusting & odious’. Degraded or not, some guides became celebrities: Salvatore Madonna (‘il capo cicerone’) was well-known for his narrative skills and general charm, as well as for his knowledge of the territory, and he even appeared in guidebooks as a colourful feature of the scene to be looked out for. Madonna seems to have been a professional type, but untrustworthy guides were not uncommon. Aviation produces about

Aviation produces about Staring into the mirror, on a Tuesday morning, you decide that your self needs all the help it can get. But where to turn? You were reading James Clear’s “

Staring into the mirror, on a Tuesday morning, you decide that your self needs all the help it can get. But where to turn? You were reading James Clear’s “ Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) means many different things to different people, but the most important parts of it have already been achieved by the

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) means many different things to different people, but the most important parts of it have already been achieved by the  BETWEEN 1956 AND 1967, the Coenties Slip on the lower tip of Manhattan was home to a group of artists who had moved to the city with grand ambitions for their work and little money to their names. In those lean years, before they were canonized, Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, Lenore Tawney, Jack Youngerman, and Delphine Seyrig all took up residence in this “down downtown,” on a dead-end street on the East River where they nested themselves among fishing ships and sailors, the changing tides and unremitting grime, living at a remove from the New York City art world. Here on “the Slip”—a commercial dock designed for transience and exchange—they lived in cheap and drafty lofts, nurturing intuitions and ideas into radical practices, producing bodies of work that would, in the end, be very much a part of the zeitgeist.

BETWEEN 1956 AND 1967, the Coenties Slip on the lower tip of Manhattan was home to a group of artists who had moved to the city with grand ambitions for their work and little money to their names. In those lean years, before they were canonized, Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, Lenore Tawney, Jack Youngerman, and Delphine Seyrig all took up residence in this “down downtown,” on a dead-end street on the East River where they nested themselves among fishing ships and sailors, the changing tides and unremitting grime, living at a remove from the New York City art world. Here on “the Slip”—a commercial dock designed for transience and exchange—they lived in cheap and drafty lofts, nurturing intuitions and ideas into radical practices, producing bodies of work that would, in the end, be very much a part of the zeitgeist. Noisy. Hysterical. Brash. The textual version of junk food. The selfie of grammar. The exclamation point attracts enormous (and undue) amounts of flak for its unabashed claim to presence in the name of emotion which some unkind souls interpret as egotistical attention-seeking. We’ve grown suspicious of feelings, particularly the big ones needing the eruption of a ! to relieve ourselves. This trend started sometime around 1900 when modernity began to mean functionality and clean straight lines (witness the sensible boxes of a Bauhaus building), rather than the “extra” mood of Victorian sensitivity or frilly playful Renaissance decorations.

Noisy. Hysterical. Brash. The textual version of junk food. The selfie of grammar. The exclamation point attracts enormous (and undue) amounts of flak for its unabashed claim to presence in the name of emotion which some unkind souls interpret as egotistical attention-seeking. We’ve grown suspicious of feelings, particularly the big ones needing the eruption of a ! to relieve ourselves. This trend started sometime around 1900 when modernity began to mean functionality and clean straight lines (witness the sensible boxes of a Bauhaus building), rather than the “extra” mood of Victorian sensitivity or frilly playful Renaissance decorations. David Deutsch is one of the most creative scientific thinkers working today, who has as a goal to understand and explain the natural world as best we can. He was a pioneer in quantum computing, and has long been an advocate of the Everett interpretation of quantum theory. He is also the inventor of

David Deutsch is one of the most creative scientific thinkers working today, who has as a goal to understand and explain the natural world as best we can. He was a pioneer in quantum computing, and has long been an advocate of the Everett interpretation of quantum theory. He is also the inventor of  What happens when lonely men, embittered by a sense of failure in the sexual marketplace, find each other and form communities on the internet? The result can be deadly.

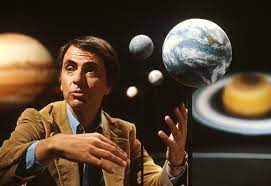

What happens when lonely men, embittered by a sense of failure in the sexual marketplace, find each other and form communities on the internet? The result can be deadly. Early in 1993, a manuscript landed in the Nature offices announcing the results of an unusual — even audacious — experiment. The investigators, led by planetary scientist and broadcaster Carl Sagan, had searched for evidence of life on Earth that could be detected from space. The results, published 30 years ago this week, were “strongly suggestive” that the planet did indeed host life. “These observations constitute a control experiment for the search for extraterrestrial life by modern interplanetary spacecraft,” the team wrote (

Early in 1993, a manuscript landed in the Nature offices announcing the results of an unusual — even audacious — experiment. The investigators, led by planetary scientist and broadcaster Carl Sagan, had searched for evidence of life on Earth that could be detected from space. The results, published 30 years ago this week, were “strongly suggestive” that the planet did indeed host life. “These observations constitute a control experiment for the search for extraterrestrial life by modern interplanetary spacecraft,” the team wrote ( Last week the literary association

Last week the literary association

“It’s not the easiest book in the world to write, but it’s something I need to get past in order to do anything else. I can’t really start writing a novel that’s got nothing to do with this,” he said. “So I just have to deal with it.”

“It’s not the easiest book in the world to write, but it’s something I need to get past in order to do anything else. I can’t really start writing a novel that’s got nothing to do with this,” he said. “So I just have to deal with it.” RELATIONS BETWEEN the United States and China have taken a dark and perilous turn. For much of this century, there was reason to hope that China could be welcomed into the liberal international order, and that its thriving there might mitigate the unavoidable tensions of great power politics. Recently, however, positions have hardened in both East and West. China has taken a discouraging, repressive turn towards personalist authoritarianism; in the United States, increasingly illiberal and politically dysfunctional, a more hawkish posture towards the People’s Republic is one of the vanishingly rare postures that garners bipartisan support in Washington.*

RELATIONS BETWEEN the United States and China have taken a dark and perilous turn. For much of this century, there was reason to hope that China could be welcomed into the liberal international order, and that its thriving there might mitigate the unavoidable tensions of great power politics. Recently, however, positions have hardened in both East and West. China has taken a discouraging, repressive turn towards personalist authoritarianism; in the United States, increasingly illiberal and politically dysfunctional, a more hawkish posture towards the People’s Republic is one of the vanishingly rare postures that garners bipartisan support in Washington.*