Henry Farrell and Mark Blyth at Good Authority:

Henry Farrell: You’ve written a very influential book on economic austerity and why Europe embraced it. Your work helps explain why Germany introduced a “debt brake” into its constitution that minimized government borrowing except under emergency conditions. Last week, the German Constitutional Court said that the debt brake prevented the government from borrowing money to finance green measures. What does this mean for Europe’s transition to a post-carbon economy?

Henry Farrell: You’ve written a very influential book on economic austerity and why Europe embraced it. Your work helps explain why Germany introduced a “debt brake” into its constitution that minimized government borrowing except under emergency conditions. Last week, the German Constitutional Court said that the debt brake prevented the government from borrowing money to finance green measures. What does this mean for Europe’s transition to a post-carbon economy?

Mark Blyth: Well, it’s not very good for it. The real question is, why do countries keep introducing pro-cyclical fiscal rules that make crises worse? In Germany, it allowed the Greens, who wanted to spend lots of money on heat pumps in every house, and the liberals, who wanted to spend no money, to join together with the social democrats to form a government. They compromised on doing the spending through what are called “off balance sheet vehicles,” which are like the “special purpose vehicles” that banks used in the run up to the financial crisis. The Court said they couldn’t do this.

Politicians don’t want to acknowledge what the carbon transition will cost. What could possibly go wrong when you hide debt from your voters, not acknowledging it as part of your balance sheet, taking the risk that interest rates go up and your asset values go down?

More here.

On the outskirts of Brandenburg an der Havel, Germany, nestled among car dealerships and hardware shops, sits a two-storey factory stuffed with solar-power secrets. It’s here where UK firm

On the outskirts of Brandenburg an der Havel, Germany, nestled among car dealerships and hardware shops, sits a two-storey factory stuffed with solar-power secrets. It’s here where UK firm  As we age, our memory declines. This is an ingrained assumption for many of us; however, according to neuroscientist Dr. Richard Restak, a neurologist and clinical professor at George Washington Hospital University School of Medicine and Health, decline is not inevitable. The author of more than 20 books on the mind, Dr. Restak has decades’ worth of experience in guiding patients with memory problems. “The Complete Guide to Memory: The Science of Strengthening Your Mind,” Dr. Restak’s latest book, includes tools such as mental exercises, sleep habits and diet that can help boost memory.

As we age, our memory declines. This is an ingrained assumption for many of us; however, according to neuroscientist Dr. Richard Restak, a neurologist and clinical professor at George Washington Hospital University School of Medicine and Health, decline is not inevitable. The author of more than 20 books on the mind, Dr. Restak has decades’ worth of experience in guiding patients with memory problems. “The Complete Guide to Memory: The Science of Strengthening Your Mind,” Dr. Restak’s latest book, includes tools such as mental exercises, sleep habits and diet that can help boost memory. Even though Kierkegaard treats despair as a spiritual and existential condition rather than just a psychological state, The Sickness Unto Death sparkles with psychological insight. Especially compelling is his diagnosis of the different forms of despair that arise from an imbalance between the various pairs that make up the human synthesis (those first folds in our sheets of paper). Too much necessity, and we lose all imagination and hope—we cannot breathe; too much possibility, and we float airily, ineffectually, above our own lives. Too much finitude, and we lose ourselves in trivial things; too much infinitude, and we’re disconnected from the world. Since life is so rarely in balance, despair is the inevitable state—but understanding this, for Kierkegaard, opens up a renewed perspective on how to live with this inevitability.

Even though Kierkegaard treats despair as a spiritual and existential condition rather than just a psychological state, The Sickness Unto Death sparkles with psychological insight. Especially compelling is his diagnosis of the different forms of despair that arise from an imbalance between the various pairs that make up the human synthesis (those first folds in our sheets of paper). Too much necessity, and we lose all imagination and hope—we cannot breathe; too much possibility, and we float airily, ineffectually, above our own lives. Too much finitude, and we lose ourselves in trivial things; too much infinitude, and we’re disconnected from the world. Since life is so rarely in balance, despair is the inevitable state—but understanding this, for Kierkegaard, opens up a renewed perspective on how to live with this inevitability. Elizabeth Bishop delighted in the postcard. It suited her poetic subject matter and her way of life—this poet of travel who was more often on the move than at home, “wherever that may be,” as she put it in her poem “Questions of Travel.” She told James Merrill in a postcard written in 1979 that she seldom wrote “anything of any value at the desk or in the room where I was supposed to be doing it—it’s always in someone else’s house, or in a bar, or standing up in the kitchen in the middle of the night.”

Elizabeth Bishop delighted in the postcard. It suited her poetic subject matter and her way of life—this poet of travel who was more often on the move than at home, “wherever that may be,” as she put it in her poem “Questions of Travel.” She told James Merrill in a postcard written in 1979 that she seldom wrote “anything of any value at the desk or in the room where I was supposed to be doing it—it’s always in someone else’s house, or in a bar, or standing up in the kitchen in the middle of the night.” K

K W

W Rather than focusing on how people and societies think and talk about morality, normative ethicists try to figure out which things are, simply, morally good or bad, and why. The philosophical sub-field of meta-ethics adopts, naturally, a ‘meta-’ perspective on the kinds of enquiry that normative ethicists engage in. It asks whether there are objectively correct answers to these questions about good or bad, or whether ethics is, rather, a realm of illusion or mere opinion.

Rather than focusing on how people and societies think and talk about morality, normative ethicists try to figure out which things are, simply, morally good or bad, and why. The philosophical sub-field of meta-ethics adopts, naturally, a ‘meta-’ perspective on the kinds of enquiry that normative ethicists engage in. It asks whether there are objectively correct answers to these questions about good or bad, or whether ethics is, rather, a realm of illusion or mere opinion. This year marks the tenth anniversary of the International Year of Quinoa (IYQ), a celebratory initiative created by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. At the inaugural 2013 IYQ, Evo Morales, then president of Bolivia, proclaimed that quinoa was “

This year marks the tenth anniversary of the International Year of Quinoa (IYQ), a celebratory initiative created by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. At the inaugural 2013 IYQ, Evo Morales, then president of Bolivia, proclaimed that quinoa was “ Born in East Berlin in 1967, Jenny Erpenbeck was 22 when the Wall that had divided her native city for her entire life fell. The socialist German Democratic Republic (GDR), the only country she had known, vanished overnight. By her own account, in the essays collected in Not a Novel: A Memoir in Pieces (2018), this historical rupture confronted her with fundamental questions about continuity and change, agency and contingency, borders and identity, liberation and loss. Although these questions have animated her fiction for more than twenty years, her most recent novel, Kairos (2021), is the first to be centered on how the radically transformative period of German reunification was experienced by those who found themselves, as she writes, “at home on the wrong side.”

Born in East Berlin in 1967, Jenny Erpenbeck was 22 when the Wall that had divided her native city for her entire life fell. The socialist German Democratic Republic (GDR), the only country she had known, vanished overnight. By her own account, in the essays collected in Not a Novel: A Memoir in Pieces (2018), this historical rupture confronted her with fundamental questions about continuity and change, agency and contingency, borders and identity, liberation and loss. Although these questions have animated her fiction for more than twenty years, her most recent novel, Kairos (2021), is the first to be centered on how the radically transformative period of German reunification was experienced by those who found themselves, as she writes, “at home on the wrong side.” On November 6th, Donald Trump emerged from a New York City courtroom, where he had testified in a civil trial alleging that he and others in the Trump Organization had committed fraud, and gave himself a great review. “I think it went very well,” he told reporters. “If you were there, and you listened, you’d see what a scam this is.” He meant that the case was a scam and not that his company was. “Everybody saw what happened today,” he went on. “And it was very conclusive.”

On November 6th, Donald Trump emerged from a New York City courtroom, where he had testified in a civil trial alleging that he and others in the Trump Organization had committed fraud, and gave himself a great review. “I think it went very well,” he told reporters. “If you were there, and you listened, you’d see what a scam this is.” He meant that the case was a scam and not that his company was. “Everybody saw what happened today,” he went on. “And it was very conclusive.” At first it was just one flower, but Emmanuel Mendoza, an undergraduate student at Texas A&M University, had worked hard to help it bloom. When this five-petaled thing burst forth from his English pea plant collection in late October, and then more flowers and even pea pods followed, he could also see, a little better, the future it might foretell on another world millions of miles from Earth. These weren’t just any pea plants. Some were grown in soil meant to mimic Mars’s inhospitable regolith, the mixture of grainy, eroded rocks and minerals that covers the planet’s surface. To that simulated regolith, Mr. Mendoza had added fertilizer called frass — the waste left after black soldier fly larvae are finished eating and digesting. Essentially, bug manure.

At first it was just one flower, but Emmanuel Mendoza, an undergraduate student at Texas A&M University, had worked hard to help it bloom. When this five-petaled thing burst forth from his English pea plant collection in late October, and then more flowers and even pea pods followed, he could also see, a little better, the future it might foretell on another world millions of miles from Earth. These weren’t just any pea plants. Some were grown in soil meant to mimic Mars’s inhospitable regolith, the mixture of grainy, eroded rocks and minerals that covers the planet’s surface. To that simulated regolith, Mr. Mendoza had added fertilizer called frass — the waste left after black soldier fly larvae are finished eating and digesting. Essentially, bug manure. Mahraganat (which means “festivals” in Arabic) is made primarily by self-taught young men from lower-class backgrounds, whose songs are considered brash, even vulgar, because they rap and sing openly about their lives with seldom a trace of modesty. Egypt’s canonical singers and composers from the 20th century, particularly Umm Kulthum, Abdel Halim Hafez, and Mohammed Abdel Wahab, possessed a virtuosic command of improvisational technique and classical repertoire. By comparison, mahraganat artists appeal first and foremost to friends from the block, weaving a unique lexicon of Arabic slang, boasts, insults, drug references, and sexual innuendo. The artists use Auto-Tune not only to add distortive, festive color to their rugged street anthems, but also for its manufacturer-intended purpose: to keep their voices in tune.

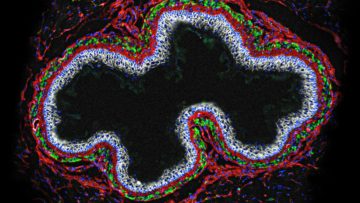

Mahraganat (which means “festivals” in Arabic) is made primarily by self-taught young men from lower-class backgrounds, whose songs are considered brash, even vulgar, because they rap and sing openly about their lives with seldom a trace of modesty. Egypt’s canonical singers and composers from the 20th century, particularly Umm Kulthum, Abdel Halim Hafez, and Mohammed Abdel Wahab, possessed a virtuosic command of improvisational technique and classical repertoire. By comparison, mahraganat artists appeal first and foremost to friends from the block, weaving a unique lexicon of Arabic slang, boasts, insults, drug references, and sexual innuendo. The artists use Auto-Tune not only to add distortive, festive color to their rugged street anthems, but also for its manufacturer-intended purpose: to keep their voices in tune. Breaking down food requires coordination across dozens of cell types and many tissues — from muscle cells and immune cells to blood and lymphatic vessels. Heading this effort is the gut’s very own network of nerve cells, known as the enteric nervous system, which weaves through the intestinal walls from the esophagus down to the rectum. This network can function nearly independently from the brain; indeed, its complexity has earned it the nickname “the second brain.” And just like the brain, it’s made up of two kinds of nervous system cells: neurons and glia.

Breaking down food requires coordination across dozens of cell types and many tissues — from muscle cells and immune cells to blood and lymphatic vessels. Heading this effort is the gut’s very own network of nerve cells, known as the enteric nervous system, which weaves through the intestinal walls from the esophagus down to the rectum. This network can function nearly independently from the brain; indeed, its complexity has earned it the nickname “the second brain.” And just like the brain, it’s made up of two kinds of nervous system cells: neurons and glia.