Ellen Wexler in Smithsonian:

On her 25th birthday in February 1947, Felicia Montealegre sent a giddy letter to her new fiancé. “Lenny, my darling, my darling!” she wrote. “I am a quarter of a century old, a very frightening fact!” Recent developments, she went on, included the arrival of a black cocker spaniel puppy (“She’s mine, my very own!”) and an impending driver’s license exam (“I drive alone all over the place, up hill and down dale, heavy traffic and all—and I’m great! So there!!”).

On her 25th birthday in February 1947, Felicia Montealegre sent a giddy letter to her new fiancé. “Lenny, my darling, my darling!” she wrote. “I am a quarter of a century old, a very frightening fact!” Recent developments, she went on, included the arrival of a black cocker spaniel puppy (“She’s mine, my very own!”) and an impending driver’s license exam (“I drive alone all over the place, up hill and down dale, heavy traffic and all—and I’m great! So there!!”).

Felicia, an actress, had been engaged to Leonard Bernstein, the 28-year-old wunderkind composer and conductor, for two months. She was, like most everyone in the man’s orbit, perilously in love with him. Still, beneath the bubbly, starry-eyed adoration, she felt something was amiss. “What’s with you?” she wrote. “You never really tell me how you feel—is it that difficult?” Come fall, the engagement was off. Then, after a four-year interlude, it was back on. A wedding quickly followed.

Yet the biggest obstacle remained: Bernstein, a closeted bisexual man, had always conducted numerous affairs with both men and women. In 1947, the secrecy had been evidently too heavy for the relationship to bear.

More here.

As a health reporter who’s been following nutrition news for decades, I’ve seen a lot of trends that made a splash — and then sank. Remember olestra, the Paleo diet and celery juice? Watch enough food fads come and go, and you realize that the most valuable nutrition guidance is built on decades of research, in which scientists have looked at a question from multiple perspectives and arrived at something like a consensus.

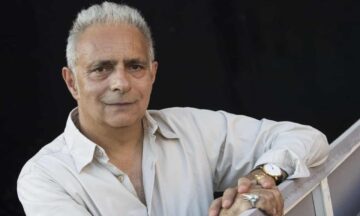

As a health reporter who’s been following nutrition news for decades, I’ve seen a lot of trends that made a splash — and then sank. Remember olestra, the Paleo diet and celery juice? Watch enough food fads come and go, and you realize that the most valuable nutrition guidance is built on decades of research, in which scientists have looked at a question from multiple perspectives and arrived at something like a consensus. Hanif Kureishi has spoken candidly of how his sense of self and privacy have been “completely eradicated” after a fall on Boxing Day last year left him unable to use his hands, arms or legs.

Hanif Kureishi has spoken candidly of how his sense of self and privacy have been “completely eradicated” after a fall on Boxing Day last year left him unable to use his hands, arms or legs. People often think they know what causes chronic depression. Surveys indicate that more than 80% of the public blames a “chemical imbalance” in the brain. That idea is widespread in pop psychology and cited in

People often think they know what causes chronic depression. Surveys indicate that more than 80% of the public blames a “chemical imbalance” in the brain. That idea is widespread in pop psychology and cited in  It is worth remembering the vast majority of what we call free-speech issues have little basis in the First Amendment, which only forbids the abridgment of speech by the government, not private organizations like magazines, cultural centers, or Hollywood production companies. In most states, for instance, it is perfectly legal for employers to fire workers for speech, as a

It is worth remembering the vast majority of what we call free-speech issues have little basis in the First Amendment, which only forbids the abridgment of speech by the government, not private organizations like magazines, cultural centers, or Hollywood production companies. In most states, for instance, it is perfectly legal for employers to fire workers for speech, as a  In “

In “ B

B Our conveniently vague or unrealistic

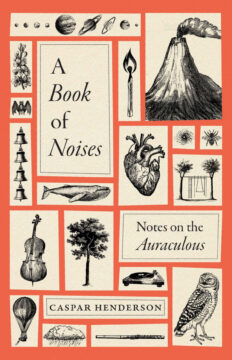

Our conveniently vague or unrealistic  Did you know that sperm whales make sounds using “lips” located near their blowholes — and that those sounds are so loud they could burst the eardrums of a human diver at close range? Or that, near the start of the Covid-19 lockdowns in Britain in 2020, residents on newly quiet streets became aware of “noisy lovemaking” by amorous hedgehogs? Or that, according to legend, churchbells in the English coastal town of Dunwich, which largely disappeared into the sea following storm surges in the 14th century, can still be heard when the tide is just right?

Did you know that sperm whales make sounds using “lips” located near their blowholes — and that those sounds are so loud they could burst the eardrums of a human diver at close range? Or that, near the start of the Covid-19 lockdowns in Britain in 2020, residents on newly quiet streets became aware of “noisy lovemaking” by amorous hedgehogs? Or that, according to legend, churchbells in the English coastal town of Dunwich, which largely disappeared into the sea following storm surges in the 14th century, can still be heard when the tide is just right? Two years ago, I gave an academic talk via Zoom on the need to limit work in order to combat the culture of burnout in the United States. Following my presentation, a senior scholar had more of a comment than a question for me. He said that “we” needed to acknowledge our privileged status among workers. When academics criticize the American work ethic, he added, we ought to recognize that most workers “can’t afford to burn out.” Burnout, I took him to be saying, was a luxury, and to complain about it was like flaunting your wealth before someone desperately poor.

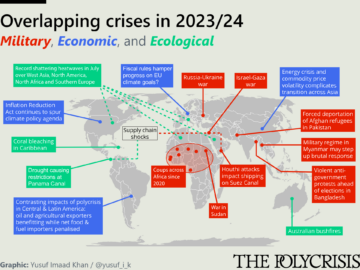

Two years ago, I gave an academic talk via Zoom on the need to limit work in order to combat the culture of burnout in the United States. Following my presentation, a senior scholar had more of a comment than a question for me. He said that “we” needed to acknowledge our privileged status among workers. When academics criticize the American work ethic, he added, we ought to recognize that most workers “can’t afford to burn out.” Burnout, I took him to be saying, was a luxury, and to complain about it was like flaunting your wealth before someone desperately poor. Tim Sahay in Polycrisis:

Tim Sahay in Polycrisis: