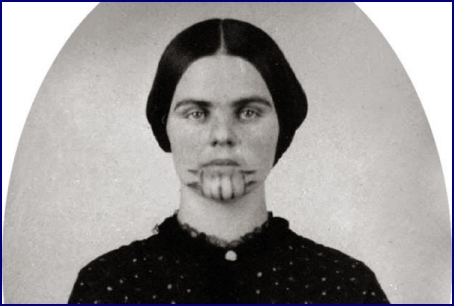

Olive Oatman

It was the charcoal they couldn’t stand.

Sister Maddy tried and tried

to get it out —bleach and scrub

till my skin peeled—

but the marks stayed,

black as the stripes

on a hawk’s wing.

Maddy took the mirror away—

each day I saw those marks

took me back,

away from the silk bustled dresses,

the shoes like vices,

the bobs and nods and mouthy words.

Back to the camp by the river.

Smoke blue as morning,

children so quiet

I was afraid at first.

He brought me tied on the back of a horse.

They took my dress,

burned it, and laughed,

put me in deerskin —so soft—

laid me on a bed of pine

with the skins circled ‘round,

a smell of earth and sweat and hide.

I choked on the smell,

couldn’t get used to the work.

Water from the river in bark buckets,

firewood in a clump on my back,

scraping the dead things he brought me—

blood, skin, and sinew

torn from the hide

like all I’d left behind.

The women hated me at first;

no one talked, just pointed,

even when my belly grew round.

Nothing changed until the night

my son was born. I’d seen

and heard how it was done.

I grabbed the sinew the old woman gave;

I stuffed my mouth with rags

and pressed my back. No sound,

no sound at all,

until his head burst out so black

the women smiled; I shouted then.

He loved me the way a hawk loves.

I’d seen them once,

talons locked in air,

falling over and under each other,

screaming,

my God, I tried to tell Maddie

she stopped her ears,

I’d forgotten the right words.

You never can go back—once you know.

Three sons in four years.

Learned how to bead moccasins,

dig cattail roots,

weave mats, and split a hare open

in one slit. I was rich as a moon

in the sky, the stars around.

That day by the river

I heard them too late,

smelled them too late,

tried to bury myself in sand;

they caught my hand

and threw me on a horse. “Home,”

they said.

Took my deerskins away,

stuffed me in black silk—

what had I don’t wrong?

Scrubbed all day at the tattoos.

Kept watch on me day and night,

for years and years.

I could not go back

to the circle of hides,

my three sons like stars,

and Him—no words for that.

I never forgot,

and when I see hawks sailing high,

talons outstretched

in a wild, tumbling fall,

I cry.

by Ann Turner

from Grass Songs

Harcourt Brace

.

Natural selection, we’re told, is the process by which nature promotes our best qualities. But a look around strains that notion. If nature selects health, beauty, and intelligence, why are most of us far from flawless?