Alexandra Jacobs at the New York Times:

What a document dump!

What a document dump!

The most delicious parts of “Cocktails With George and Martha,” Philip Gefter’s unapologetically obsessive new book about “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” — the dark ’n’ stormy, oft-revived 1962 Broadway hit by Edward Albee that became a moneymaking movie and an eternal marriage meme — are diary excerpts from the screenwriter Ernest Lehman. (Gefter calls the diary “unpublished,” but at least some of it surfaced in the turn-of-the-millennium magazine Talk, now hard to find.)

That Lehman is no longer a household name, if he ever was, is one of showbiz history’s many injustices. Before the thankless task of condensing Albee’s three-hour play for the big screen (on top of producing), he wrote the scripts for “North by Northwest” (1959), arguably Hitchcock’s greatest, and with some help, “Sweet Smell of Success” (1957).

more here.

We find similar ideas of a transcendent ego in both Kant and the Upanishads. We find a rejection of free will in Schopenhauer and Ramana Maharshi. What should we make of this overlap between Western and Indian philosophy? Chakravarthi Ram-Prasad argues both became gripped by the same question.

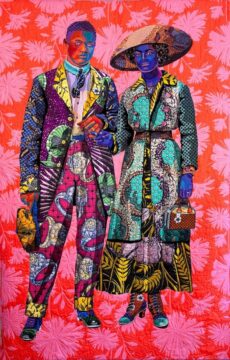

We find similar ideas of a transcendent ego in both Kant and the Upanishads. We find a rejection of free will in Schopenhauer and Ramana Maharshi. What should we make of this overlap between Western and Indian philosophy? Chakravarthi Ram-Prasad argues both became gripped by the same question. Brooklyn-based artist

Brooklyn-based artist  Elizabeth Amelia Gloucester appeared in the census for the final time on June 8, 1880. The census enumerators who crisscrossed Brooklyn Heights were no doubt surprised to find a wealthy Black woman presiding over Remsen House, the grand boarding hotel not far from Brooklyn City Hall that served the white professional classes. Ms. Gloucester was a pillar of the

Elizabeth Amelia Gloucester appeared in the census for the final time on June 8, 1880. The census enumerators who crisscrossed Brooklyn Heights were no doubt surprised to find a wealthy Black woman presiding over Remsen House, the grand boarding hotel not far from Brooklyn City Hall that served the white professional classes. Ms. Gloucester was a pillar of the  Since its inception with the

Since its inception with the  Instruments deployed in the ocean starting in 2004

Instruments deployed in the ocean starting in 2004  THE CANARY ISLANDS—

THE CANARY ISLANDS— In an anonymously published essay, “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists,” George Eliot set out her objections to “mind-and-millinery” novels: those books featuring dazzling heroines—eloquent, accomplished, almost godly—who set off into the world solely in pursuit of an amiable husband. Castigating the genre for its “drivelling” narratives, clichéd characters, and hackneyed morals, Eliot argued that novels that posit marriage as a woman’s ultimate aim and achievement only “confirm the popular prejudice against the more solid education of women.” In her own writing, Eliot set out not just to rehash the “marriage plot” but to expose and dissect it: Her sweeping novels show her utterly human characters grappling with the harsh disparities between societal expectations of married life and their own, often painful experiences of it.

In an anonymously published essay, “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists,” George Eliot set out her objections to “mind-and-millinery” novels: those books featuring dazzling heroines—eloquent, accomplished, almost godly—who set off into the world solely in pursuit of an amiable husband. Castigating the genre for its “drivelling” narratives, clichéd characters, and hackneyed morals, Eliot argued that novels that posit marriage as a woman’s ultimate aim and achievement only “confirm the popular prejudice against the more solid education of women.” In her own writing, Eliot set out not just to rehash the “marriage plot” but to expose and dissect it: Her sweeping novels show her utterly human characters grappling with the harsh disparities between societal expectations of married life and their own, often painful experiences of it. ALMOST IMMEDIATELY after melodrama had its heyday in the mid-19th century, it began to be mocked for being obsolete. In an 1890 burlesque of Victorien Sardou’s La Tosca, the play later adapted into a more famous opera, the police chief Scarpia proudly admits that, as a villain intent on “possess[ing]” the play’s titular heroine, he is a vestige of “that dark age / when curdling melodrama held the stage.” Belonging to a genre that has come to feel more campy than poignant, even villains like Scarpia can’t take themselves seriously. And yet, no matter how many generations have claimed to have evolved away from a genre besmirched for its expressive storytelling and moral polarities, melodrama has retained its power as a way for artists to represent the world and as a lens for critics to interpret what they see.

ALMOST IMMEDIATELY after melodrama had its heyday in the mid-19th century, it began to be mocked for being obsolete. In an 1890 burlesque of Victorien Sardou’s La Tosca, the play later adapted into a more famous opera, the police chief Scarpia proudly admits that, as a villain intent on “possess[ing]” the play’s titular heroine, he is a vestige of “that dark age / when curdling melodrama held the stage.” Belonging to a genre that has come to feel more campy than poignant, even villains like Scarpia can’t take themselves seriously. And yet, no matter how many generations have claimed to have evolved away from a genre besmirched for its expressive storytelling and moral polarities, melodrama has retained its power as a way for artists to represent the world and as a lens for critics to interpret what they see. In antiquity humans were referred to as “mortals,” which meant that they were destined not only to die but also to suffer loss, misfortune, and disaster. By comparison with the immortal gods, even the loftiest mortals are losers in the long run (as Achilles realizes in Hades). In his book In Praise of Failure, the philosopher and essayist Costica Bradatan reminds us that we flash into existence between “two instantiations of nothingness,” namely the nothingness before we were born and the one after we die. Each one of us, ontologically speaking, is next to nothing. And each one of us, despite our precarious condition, has something to lose. “Myths, religion, spirituality, philosophy, science, works of art and literature”—all, according to Bradatan, seek to make our next-to-nothingness “a little more bearable.”

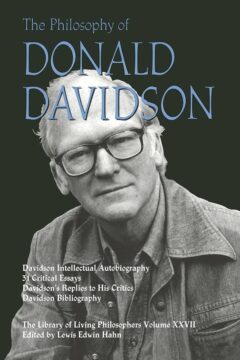

In antiquity humans were referred to as “mortals,” which meant that they were destined not only to die but also to suffer loss, misfortune, and disaster. By comparison with the immortal gods, even the loftiest mortals are losers in the long run (as Achilles realizes in Hades). In his book In Praise of Failure, the philosopher and essayist Costica Bradatan reminds us that we flash into existence between “two instantiations of nothingness,” namely the nothingness before we were born and the one after we die. Each one of us, ontologically speaking, is next to nothing. And each one of us, despite our precarious condition, has something to lose. “Myths, religion, spirituality, philosophy, science, works of art and literature”—all, according to Bradatan, seek to make our next-to-nothingness “a little more bearable.” Decades ago, I argued that indeterminacy of interpretation, construed in the terminology of Husserl’s phenomenology and Saussure’s conception of language, was very close to Derrida’s “deconstruction.” I have come to see that the very structure of Davidson’s account of language commits him to a version of “dissemination,” the fluidity and “play” of ascriptions of meaning. The core of Davidson’s account of language and interpretation guarantees that natural languages will be disseminative.

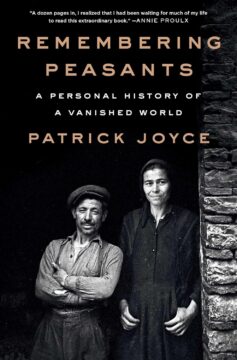

Decades ago, I argued that indeterminacy of interpretation, construed in the terminology of Husserl’s phenomenology and Saussure’s conception of language, was very close to Derrida’s “deconstruction.” I have come to see that the very structure of Davidson’s account of language commits him to a version of “dissemination,” the fluidity and “play” of ascriptions of meaning. The core of Davidson’s account of language and interpretation guarantees that natural languages will be disseminative. Don’t impress me with peasant virtues, said Chekhov, I have peasant blood in my veins. Patrick Joyce has the blood too. His people won a living from the hard lands of Dúiche Seoighe, or Joyce Country, which stretch from Loughs Corrib and Mask to the Atlantic Ocean and straddle the border of County Mayo and County Galway. Although his father took the family to England in 1930, he brought his sons back every year and they would fall asleep night after night listening to kitchen talk in English and Irish. Joyce knows what he is talking about, and if his peasants are not always virtuous, they are at least vivid and real.

Don’t impress me with peasant virtues, said Chekhov, I have peasant blood in my veins. Patrick Joyce has the blood too. His people won a living from the hard lands of Dúiche Seoighe, or Joyce Country, which stretch from Loughs Corrib and Mask to the Atlantic Ocean and straddle the border of County Mayo and County Galway. Although his father took the family to England in 1930, he brought his sons back every year and they would fall asleep night after night listening to kitchen talk in English and Irish. Joyce knows what he is talking about, and if his peasants are not always virtuous, they are at least vivid and real. There is a well-known passage in

There is a well-known passage in