Salman Hameed in Science:

Early in 2007, biologists and anthropologists at universities across the United States received an unsolicited gift of an 850-page, colored Atlas of Creation, produced by a Muslim creationist, Adnan Oktar, who goes by the pen name of Harun Yahya (Science, 16 February 2007, p. 925). The atlas was a timely notice that, although the last couple of decades have seen an increasing confrontation over the teaching of evolution in the United States, the next major battle over evolution is likely to take place in the Muslim world (i.e., predominantly Islamic countries, as well as in countries where there are large Muslim populations). Relatively poor education standards, in combination with frequent misinformation about evolutionary ideas, make the Muslim world a fertile ground for rejection of the theory. In addition, there already exists a growing and highly influential Islamic creationist movement (1). Biological evolution is still a relatively new concept for a majority of Muslims, and a serious debate over its religious compatibility has not yet taken place. It is likely that public opinion on this issue will be shaped in the next decade or so because of rising education levels in the Muslim world and the increasing importance of biological sciences.

More here. And related to this, again Salman Hameed in The Guardian this time:

How should scientists respond to the rising challenge of creationism in the Muslim world? Despite surveys showing hostility towards evolution, there is also an overwhelmingly pro-science attitude. This is particularly true for sciences that have practical and technological benefits. The message about evolution in the Islamic world therefore needs to be framed in a way that emphasises practical applications and shows that it is the bedrock of modern biology. This is the approach advocated in the US in the recent National Academy of Sciences publication Science, Evolution, and Creationism.

How should scientists respond to the rising challenge of creationism in the Muslim world? Despite surveys showing hostility towards evolution, there is also an overwhelmingly pro-science attitude. This is particularly true for sciences that have practical and technological benefits. The message about evolution in the Islamic world therefore needs to be framed in a way that emphasises practical applications and shows that it is the bedrock of modern biology. This is the approach advocated in the US in the recent National Academy of Sciences publication Science, Evolution, and Creationism.

The arguments for evolution will have to be framed differently in each country. The national academies of Muslim countries can tailor the specifics of the message according to the political and cultural realities of their respective communities. For example, while evolution is included in the high school curricula of both Turkey and Pakistan, the challenges faced by schools in secular Turkey are very different from those in highly religious Pakistan.

Crucially, if a link between evolution and atheism is stressed, as some prominent scientists in the west have been advocating, this will undoubtedly cut short the dialogue and the vast majority of people in the Muslim world will choose religion over evolution. Muslim creationists know this and they have been stressing this link in their anti-evolution works.

More here.

C.M. Naim in OutlookIndia:

The book is titled Ham Ma’en Lashkar-e-Taiba Ki (‘We, the Mothers of Lashkar-e-Taiba’); its compiler styles herself Umm-e-Hammad; and it is published by Dar-al-Andulus, Lahore. Its three volumes have the same garish cover, showing a large pink rose, blood dripping from it, superimposed on a landscape of mountains and pine trees The first volume, running to 381 pages, originally came out in November 1998, and was reprinted in April 2001. |

The second and third volumes, with 377 and 262 pages, respectively, came out in October 2003. Each printing consisted of 1100 copies. Portions of the book—perhaps much of it—also appeared in the Lashkar’s journal, Mujalla Al-Da’wa. The second and third volumes, with 377 and 262 pages, respectively, came out in October 2003. Each printing consisted of 1100 copies. Portions of the book—perhaps much of it—also appeared in the Lashkar’s journal, Mujalla Al-Da’wa.

Here is how the publisher, Muhammad Ramzan Asari, describes the book’s contents and purpose. The book at hand, Ham Ma’en Lashkar-e Taiba Ki, is a distillation of the tireless labor and far-flung travels of our respected Apa (‘Elder Sister’), Umm-e-Hammad, who is in-charge of the Lashkar’s Women section, and also happens to be an Umm-e-Shahidain (‘Mother of Two martyrs’)…. [I could be misreading the text, for I found no reference to any of her sons except one, whom she described as a very much alive mujahid.] Her poems are on the lips of the mujahdin. Numerous young men read or heard her poems and, consequently, set out to perform jihad, many of them gaining Paradise…. Our workers should make this book a part of the readings for the ladies at homes to awaken the fervour for jihad in the breasts of our mothers and sisters. (I.13.)

In her preface, Umm-e Hammad describes her own conversion to the cause at some length.

More here. |

Art, so it seems to me, represents the triumph of private feeling over public pressures, or at least the ability of private feeling to assert itself in the face of public pressures and public values. I would argue that true art is always characterized by its unto-itself-ness, its freestanding-ness, its independence. This is not to say that the arts are untouched by the rest of life, only that they are affected by it in their own fashion. I cannot insist too much on this point. It is certainly a marginal view at present, when most discussions about contemporary art tend to focus on the artist’s social and economic success. Artists such as Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons are famous for being famous, and what generally interests people about their work is not what they do but why the particular sort of thing that they do has found favor in the marketplace. Such questions, which keep journalists working overtime, are by no means regarded as merely journalistic. Contextualism has a great deal of intellectual cachet: in the past generation, the work of artists from Rembrandt to Picasso has been interpreted by some of the most widely respected art historians as fueled not by imaginative necessity but by market forces, and the argument goes far beyond the perfectly reasonable supposition that some artists have been savvy salesmen.

more from TNR here.

Look at enough dinosaur displays and you begin to ask questions beyond the scope of the exhibit. What would a sleeping dinosaur look like? How do you clean one of these things? Where’s the cafeteria? It’s not that the dinosaurs themselves are uninteresting — the danger they suggest infuses museum halls with a sense of potential energy. Instead, it’s the fact that once you’ve seen one T. Rex, all other T. Rexes start to look alike. And there are a lot of them out there. Indeed, dinosaur mounts have become so fundamental to our idea of what makes a natural history museum that it can be difficult to imagine the institutions ever existing without them. Yet the “fearfully great lizards” made a relatively late appearance in the tradition of collecting and displaying the Earth’s artifacts. The Egyptians were collecting exotic wildlife as early as 1400 B.C., and the Europeans started housing natural curiosities in wunderkammers in the 16th century, but dinosaurs didn’t appear until the 19th. It wasn’t until 1868 that the first dinosaur was mounted for exhibition, at Philadelphia’s Academy of Natural Sciences. This year, the museum celebrates the 140th of that influential move with a new exhibit, “Hadrosaurus foulkii: The Dinosaur That Changed the World.”

more from The Smart Set here.

DURING THE PANIC of 1907, the nation’s most powerful banker, J. P. Morgan, brokered a solution to the crisis behind the closed doors of his personal library in New York City. Faced with the total collapse of the financial system, Morgan gathered together the nation’s banking titans into one wing of the library and locked the door, refusing to let them out until they had pledged to help one another through the crisis. Morgan stopped the panic in its tracks, and his modus operandi – hammering out deals in secrecy – has become the conventional method of managing threats to the nation’s economy. This year, the response to the crisis on Wall Street started that way, too. As venerable Lehman Brothers teetered on collapse, the nation’s top bankers gathered in the offices of the Federal Reserve for a closed-door meeting at which the Treasury secretary urged them to rescue the beleaguered firm on their own. When that effort failed, Secretary Henry Paulson demanded Congress cough up three quarters of a trillion dollars to buy up bad assets, submitting next to nothing to make his case. The message was simple enough: Trust us – we know what we’re doing. This time, however, something strange happened. A sprawling network of experts in economics and finance began picking apart the Paulson plan – live, in public, on blogs.

more from Boston Globe Ideas here.

From The New York Times:

As director of Stanford’s Center for Human Embryonic Stem Cell Research and Education, Renee A. Reijo Pera, 49, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology, works at ground zero of the controversy over human embryonic stem cells. She uses human embryos to create new cells that will eventually be coaxed into becoming eggs and sperm. In other research, she has also identified one of the first genes associated with human infertility. The questions and answers below are edited from a two-hour conversation and a subsequent telephone interview.

As director of Stanford’s Center for Human Embryonic Stem Cell Research and Education, Renee A. Reijo Pera, 49, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology, works at ground zero of the controversy over human embryonic stem cells. She uses human embryos to create new cells that will eventually be coaxed into becoming eggs and sperm. In other research, she has also identified one of the first genes associated with human infertility. The questions and answers below are edited from a two-hour conversation and a subsequent telephone interview.

Q. IN SPEECHES, YOU SAY THAT STEM CELL RESEARCH SHOULD BE THOUGHT OF AS A WOMEN’S HEALTH ISSUE. WHY?

A. Because in my lab, we’re using stem cell research to look for ways to make fertility treatments safer and more rational. Considering all the heartbreak and expense of infertility treatments, this sort of research is something I believe women have a big stake in defending. Right now, we don’t fully know what a healthy embryo in a Petri dish looks like. Because of this, I.V.F. clinics often insert multiple embryos into women to try to increase the odds of a successful implantation. Patients frequently have multiple births or devastating miscarriages. Half the time, the embryos don’t make it. If we could figure out what a healthy embryo looked like and what the best media was to grow it in, we’d cut down on that.

More here.

Monday, December 15, 2008

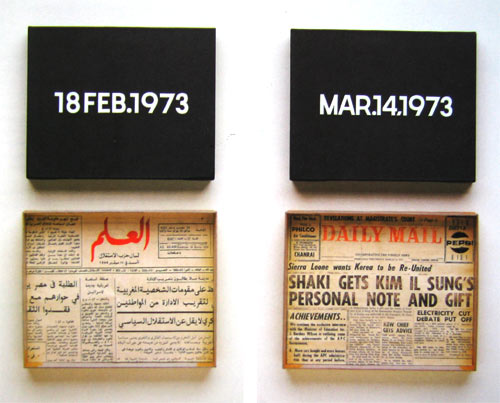

On Kawara. TODAY.

More here, here, and here.

Note: thanks to Asad Raza.

Sunday, December 14, 2008

Edward Miguel in the Boston Review:

I have visited Busia every year since 1997 to help local development-oriented nonprofit organizations design and evaluate their rural programs. In so doing, I have been exposed to impressive changes that are mirrored throughout the country. Kenyan economic growth rates surged between 2002 and 2007, achieving levels not seen since the 1970s. Last summer Nairobi’s never-ending traffic jams of imported Japanese cars were but one tangible indication that Kenyans were suddenly on the move. Construction projects were everywhere, as developers took advantage of the unexpected spike in land values. New productive sectors, like same-day cut flower exports to Europe, employed tens of thousands of workers. Like a fever that had suddenly broken, the resignation and fear of the 1990s were replaced by energy, optimism, and a feeling that there was no time to lose.

I have visited Busia every year since 1997 to help local development-oriented nonprofit organizations design and evaluate their rural programs. In so doing, I have been exposed to impressive changes that are mirrored throughout the country. Kenyan economic growth rates surged between 2002 and 2007, achieving levels not seen since the 1970s. Last summer Nairobi’s never-ending traffic jams of imported Japanese cars were but one tangible indication that Kenyans were suddenly on the move. Construction projects were everywhere, as developers took advantage of the unexpected spike in land values. New productive sectors, like same-day cut flower exports to Europe, employed tens of thousands of workers. Like a fever that had suddenly broken, the resignation and fear of the 1990s were replaced by energy, optimism, and a feeling that there was no time to lose.

But that feeling dissipated quickly in the weeks following Kenya’s disputed December 27, 2007 presidential election. The incumbent president Mwai Kibaki was reelected, allegedly through heavy ballot-box rigging. The results, and subsequent violent opposition protests and ethnic clashes, surprised many Kenyans and most observers, who thought that the elections would be free and fair and that they would help Kenya turn the corner on its autocratic past. The government power-sharing deal that Kofi Annan negotiated between the government and opposition, after two months of bloodshed, has instilled tentative hope.

The recent violence in Kenya is a heartbreaking disappointment, but the Lazarus story I witnessed in Busia—though it may have been temporary—is being repeated in hundreds of cities, towns, and villages, not just in Kenya, but all over Africa. Economic growth rates are at historic highs and democratization appears finally to be taking root. The question emerges: Will Africa be the world’s next development miracle?

More here.

Malcolm Gladwell in The New Yorker:

One of the most important tools in contemporary educational research is “value added” analysis. It uses standardized test scores to look at how much the academic performance of students in a given teacher’s classroom changes between the beginning and the end of the school year. Suppose that Mrs. Brown and Mr. Smith both teach a classroom of third graders who score at the fiftieth percentile on math and reading tests on the first day of school, in September. When the students are retested, in June, Mrs. Brown’s class scores at the seventieth percentile, while Mr. Smith’s students have fallen to the fortieth percentile. That change in the students’ rankings, value-added theory says, is a meaningful indicator of how much more effective Mrs. Brown is as a teacher than Mr. Smith.

One of the most important tools in contemporary educational research is “value added” analysis. It uses standardized test scores to look at how much the academic performance of students in a given teacher’s classroom changes between the beginning and the end of the school year. Suppose that Mrs. Brown and Mr. Smith both teach a classroom of third graders who score at the fiftieth percentile on math and reading tests on the first day of school, in September. When the students are retested, in June, Mrs. Brown’s class scores at the seventieth percentile, while Mr. Smith’s students have fallen to the fortieth percentile. That change in the students’ rankings, value-added theory says, is a meaningful indicator of how much more effective Mrs. Brown is as a teacher than Mr. Smith.

It’s only a crude measure, of course. A teacher is not solely responsible for how much is learned in a classroom, and not everything of value that a teacher imparts to his or her students can be captured on a standardized test. Nonetheless, if you follow Brown and Smith for three or four years, their effect on their students’ test scores starts to become predictable: with enough data, it is possible to identify who the very good teachers are and who the very poor teachers are. What’s more—and this is the finding that has galvanized the educational world—the difference between good teachers and poor teachers turns out to be vast.

Eric Hanushek, an economist at Stanford, estimates that the students of a very bad teacher will learn, on average, half a year’s worth of material in one school year. The students in the class of a very good teacher will learn a year and a half’s worth of material. That difference amounts to a year’s worth of learning in a single year. Teacher effects dwarf school effects: your child is actually better off in a “bad” school with an excellent teacher than in an excellent school with a bad teacher. Teacher effects are also much stronger than class-size effects. You’d have to cut the average class almost in half to get the same boost that you’d get if you switched from an average teacher to a teacher in the eighty-fifth percentile. And remember that a good teacher costs as much as an average one, whereas halving class size would require that you build twice as many classrooms and hire twice as many teachers.

More here.

Steve Coates in the New York Times:

You have to admire a scholar who can produce a small library of erudite, elegant and accessible books on American history, the New Testament and his own powerful brand of Roman Catholicism, winning a Pulitzer Prize along the way. And you have to be impressed by a plucky Spanish provincial, in the dangerous days of Nero and Domitian, who could manage to earn a handsome living writing dirty poems for the urban sophisticates of ancient Rome. But can you condone what they get up to under a single set of covers? “Martial’s Epigrams,” Garry Wills’s enthusiastic verse translations of Marcus Valerius Martialis, Rome’s most anatomically explicit poet, offers a chance to find out.

You have to admire a scholar who can produce a small library of erudite, elegant and accessible books on American history, the New Testament and his own powerful brand of Roman Catholicism, winning a Pulitzer Prize along the way. And you have to be impressed by a plucky Spanish provincial, in the dangerous days of Nero and Domitian, who could manage to earn a handsome living writing dirty poems for the urban sophisticates of ancient Rome. But can you condone what they get up to under a single set of covers? “Martial’s Epigrams,” Garry Wills’s enthusiastic verse translations of Marcus Valerius Martialis, Rome’s most anatomically explicit poet, offers a chance to find out.

The pairing is not as counterintuitive as one might imagine. Wills, who has a Ph.D. in classics and who once taught ancient Greek at Johns Hopkins, has long kept a foot in the ancient world. His Pulitzer winner, “Lincoln at Gettysburg,” brilliantly analyzed Lincoln’s greatest speech in terms of the conventions of ancient Greek funeral orations, and he has also translated the Latin of St. Augustine’s “Confessions.”

Martial, though, was no saint. Arriving in Rome around A.D. 64, he spent much of the next four decades composing short topical verse about life in the big city, an urban panorama as broad, as varied and as full of depraved humanity as any to have survived from classical times.

More here.

///

Adam's Complaint

Denise Levertov

Some people,

no matter what you give them,

still want the moon.

The bread,

the salt,

white meat and dark,

still hungry.

The marriage bed

and the cradle,

still empty arms.

You give them land,

their own earth under their feet,

still they take to the roads.

And water: dig them the deepest well,

still it's not deep enough

to drink the moon from.

.

Christopher Hitchens in The Atlantic Monthly:

The thumbnail social history of the United States, as Godfrey Hodgson (the author of America in Our Time) once phrased it to me, is as follows: agrarian population moves as soon as it can to the cities, and then consummates the process by evacuating the cities for the suburbs. More Americans now live in the suburbs than anywhere else, and more do so by choice. Anachronisms of two kinds persist in respect of this phenomenon. The first is the apparently unshakable belief of political candidates that they will sound better, and appear more authentic, if they can claim to come from a small town (something we were almost spared this year, until the chiller from Wasilla). The second is the continued stern disapproval of anything “suburban” by the strategic majority of our country's intellectuals. The idiocy of rural life? If you must. The big city? All very well. Bohemia, or perhaps Paris or Prague? Yes indeed. The suburbs? No thank you.

The thumbnail social history of the United States, as Godfrey Hodgson (the author of America in Our Time) once phrased it to me, is as follows: agrarian population moves as soon as it can to the cities, and then consummates the process by evacuating the cities for the suburbs. More Americans now live in the suburbs than anywhere else, and more do so by choice. Anachronisms of two kinds persist in respect of this phenomenon. The first is the apparently unshakable belief of political candidates that they will sound better, and appear more authentic, if they can claim to come from a small town (something we were almost spared this year, until the chiller from Wasilla). The second is the continued stern disapproval of anything “suburban” by the strategic majority of our country's intellectuals. The idiocy of rural life? If you must. The big city? All very well. Bohemia, or perhaps Paris or Prague? Yes indeed. The suburbs? No thank you.

The achievement of Richard Yates's Revolutionary Road was to anatomize the ills and woes of suburbia while simultaneously satirizing those suburbanites and others who thought that they themselves were too good for the 'burbs.

More here.

Wendy O'Shea-Meddour in the International Literary Quarterly:

Of Pakistan, we are told:

The local people would hardly be there, in their own land, or would be there only as ciphers swept aside by the agents of the faith. It is a dreadful mangling of history. It is a convert’s view; that is all that can be said for it. History has become a kind of neurosis. Too much has to be ignored or angled; there is too much fantasy. This fantasy isn’t in the books alone; it affects people’s lives. (329)

Islam is found guilty of inducing mental illness on a national scale because it is an “Arab” religion with sacred places in Arab lands. According to this peculiar thesis, Arabs do not suffer from neurosis because they are not “converts.” The narrator fails to mention that Arabs were generally polytheists at the time of the prophet Muhammad and in order to become Muslim necessarily “converted.” Perhaps this point is dismissed because the narrator believes that the ‘sacred places” of Arabs are “in their own lands”? Assuming that this is the reasoning, it would follow that European and American Christians and Jews suffer from a similar “neurosis” because their “sacred places” are abroad. However, it is clear that in the narrator’s opinion, Western Christians and Jews are mentally sound. The logic behind Naipaul’s argument is impossible to follow. As Eqbal Ahmed asks,

Islam is found guilty of inducing mental illness on a national scale because it is an “Arab” religion with sacred places in Arab lands. According to this peculiar thesis, Arabs do not suffer from neurosis because they are not “converts.” The narrator fails to mention that Arabs were generally polytheists at the time of the prophet Muhammad and in order to become Muslim necessarily “converted.” Perhaps this point is dismissed because the narrator believes that the ‘sacred places” of Arabs are “in their own lands”? Assuming that this is the reasoning, it would follow that European and American Christians and Jews suffer from a similar “neurosis” because their “sacred places” are abroad. However, it is clear that in the narrator’s opinion, Western Christians and Jews are mentally sound. The logic behind Naipaul’s argument is impossible to follow. As Eqbal Ahmed asks,

Who is not a convert? By Naipaul’s definition, if Iranians are converted Muslims, then Americans are converted Christians, the Japanese are converted Buddhists, and the Chinese, large numbers of them, are converted Buddhists as well. Everybody is converted because at the beginning every religion had only a few followers. Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Judaism, all prophetic religions developed through conversion. In that sense, his organising thesis should not exclude anyone. (Ahmad 9-10)

More here.

My face is symmetrical. Therefore, the situation is completely resolved. My voice is melodious and, when not utterly aloof, slightly flirtatious. My posture, walk, and way of slowly shifting my weight from one hip to the other while twirling my hair absentmindedly as I gaze off into an untroubled haze are all compelling as hell to ruminate upon, in silent contemplation, while the rest of the world pauses. I even smell great. You’re in for a rare treat, sensory-input-wise, being around me. Go ahead. Soak it in. Feast your eyes. This is one of those moments. For you. So you see, we have no cause for distress anymore, in terms of whatever that may have been that was temporarily impeding the immediate gratification of my every wish.

more from The Onion here.

If he were less shy and had a funny accent, David Plouffe would be every bit the household name that James Carville is—perhaps even going on Oprah and taking cameo roles in Hollywood movies. Plouffe is, after all, “the unsung hero” of the “best political campaign in the history of the United States of America”—which is how Barack Obama described him before a global television audience, in the mother of all shout-outs, on the night he was elected Leader of the Free World. At 41, Plouffe (rhymes with “no fluff”) will probably never top his historic achievement of managing the campaign that gave this nation its first African-American commander in chief. The juggernaut Plouffe led, which grew to a payroll of 5,000 before Election Day, raised record amounts of cash from millions of small donors, defeated the once-invincible Hillary Clinton machine, and crushed the flailing Republican nominee, John McCain. Obama’s success was so overwhelming that it’s hard to remember those early days when the freshman senator from Illinois was the longest of long-shots and the darkest of dark horses in a country still troubled by issues of race.

more from Portfolio here.

Saturday, December 13, 2008

Greg Beato in Reason:

Five years ago, there were seven fake judges giving us our day (and occasional evening hour) in court. Now there are nearly twice that many, with three new shows (Judge Karen, Judge Jeanine Pirro, and Family Court With Judge Penny) debuting in September 2008 alone. At least one other, Street Judge, is on the way. They're there because in the ever-shrinking world of television syndication, where competition from cable and the Internet has made Oprah-sized hits as rare as silk ascots on The Jerry Springer Show, the new dream is a steady 1.5 Nielsen rating on a weekly budget of no more than $500,000. Justice porn, it turns out, is a fairly reliable way to achieve that end: Find a sassy real-life jurist with an itch for the big time, throw some penny-ante miscreants at her mercy, and let the premature adjudication begin.

Five years ago, there were seven fake judges giving us our day (and occasional evening hour) in court. Now there are nearly twice that many, with three new shows (Judge Karen, Judge Jeanine Pirro, and Family Court With Judge Penny) debuting in September 2008 alone. At least one other, Street Judge, is on the way. They're there because in the ever-shrinking world of television syndication, where competition from cable and the Internet has made Oprah-sized hits as rare as silk ascots on The Jerry Springer Show, the new dream is a steady 1.5 Nielsen rating on a weekly budget of no more than $500,000. Justice porn, it turns out, is a fairly reliable way to achieve that end: Find a sassy real-life jurist with an itch for the big time, throw some penny-ante miscreants at her mercy, and let the premature adjudication begin.

Explicitly moral, obscenely didactic, showcasing a perversely distorted view of the American legal system, justice porn is a potent, ubiquitous presence in our lives, and at least as influential as the cartoon mayhem of Saints Row 2 or Young Jeezy's latest ode to thug life. And yet has the Federal Communications Commission's airwave fresheners ever knitted their vigilant brows over Judge Judy's contempt for the petitioners who enter her chambers seeking some facsimile of fairness? Will Hillary Clinton ever make alarmist speeches about the way these shows desensitize viewers to due process while glorifying judicial misconduct? When will the obsessive-compulsive filth inspectors at the Parents Television Council record every act of gratuitous gavel banging that occurs on these shows over a two-week period? Don't they know that grown-ups—naive and malleable grown-ups with a natural curiosity about civil litigation—are watching?

More here.

Ethan A. Nadelmann in the Wall Street Journal:

Today is the 75th anniversary of that blessed day in 1933 when Utah became the 36th and deciding state to ratify the 21st amendment, thereby repealing the 18th amendment. This ended the nation's disastrous experiment with alcohol prohibition.

Today is the 75th anniversary of that blessed day in 1933 when Utah became the 36th and deciding state to ratify the 21st amendment, thereby repealing the 18th amendment. This ended the nation's disastrous experiment with alcohol prohibition.

It's already shaping up as a day of celebration, with parties planned, bars prepping for recession-defying rounds of drinks, and newspapers set to publish cocktail recipes concocted especially for the day.

But let's hope it also serves as a day of reflection. We should consider why our forebears rejoiced at the relegalization of a powerful drug long associated with bountiful pleasure and pain, and consider too the lessons for our time.

The Americans who voted in 1933 to repeal prohibition differed greatly in their reasons for overturning the system. But almost all agreed that the evils of failed suppression far outweighed the evils of alcohol consumption.

The change from just 15 years earlier, when most Americans saw alcohol as the root of the problem and voted to ban it, was dramatic. Prohibition's failure to create an Alcohol Free Society sank in quickly. Booze flowed as readily as before, but now it was illicit, filling criminal coffers at taxpayer expense.

More here.

How should scientists respond to the rising challenge of creationism in the Muslim world? Despite surveys showing hostility towards evolution, there is also an overwhelmingly pro-science attitude. This is particularly true for sciences that have practical and technological benefits. The message about evolution in the Islamic world therefore needs to be framed in a way that emphasises practical applications and shows that it is the bedrock of modern biology. This is the approach advocated in the US in the recent National Academy of Sciences publication Science, Evolution, and Creationism.