Edward Miguel in the Boston Review:

I have visited Busia every year since 1997 to help local development-oriented nonprofit organizations design and evaluate their rural programs. In so doing, I have been exposed to impressive changes that are mirrored throughout the country. Kenyan economic growth rates surged between 2002 and 2007, achieving levels not seen since the 1970s. Last summer Nairobi’s never-ending traffic jams of imported Japanese cars were but one tangible indication that Kenyans were suddenly on the move. Construction projects were everywhere, as developers took advantage of the unexpected spike in land values. New productive sectors, like same-day cut flower exports to Europe, employed tens of thousands of workers. Like a fever that had suddenly broken, the resignation and fear of the 1990s were replaced by energy, optimism, and a feeling that there was no time to lose.

I have visited Busia every year since 1997 to help local development-oriented nonprofit organizations design and evaluate their rural programs. In so doing, I have been exposed to impressive changes that are mirrored throughout the country. Kenyan economic growth rates surged between 2002 and 2007, achieving levels not seen since the 1970s. Last summer Nairobi’s never-ending traffic jams of imported Japanese cars were but one tangible indication that Kenyans were suddenly on the move. Construction projects were everywhere, as developers took advantage of the unexpected spike in land values. New productive sectors, like same-day cut flower exports to Europe, employed tens of thousands of workers. Like a fever that had suddenly broken, the resignation and fear of the 1990s were replaced by energy, optimism, and a feeling that there was no time to lose.

But that feeling dissipated quickly in the weeks following Kenya’s disputed December 27, 2007 presidential election. The incumbent president Mwai Kibaki was reelected, allegedly through heavy ballot-box rigging. The results, and subsequent violent opposition protests and ethnic clashes, surprised many Kenyans and most observers, who thought that the elections would be free and fair and that they would help Kenya turn the corner on its autocratic past. The government power-sharing deal that Kofi Annan negotiated between the government and opposition, after two months of bloodshed, has instilled tentative hope.

The recent violence in Kenya is a heartbreaking disappointment, but the Lazarus story I witnessed in Busia—though it may have been temporary—is being repeated in hundreds of cities, towns, and villages, not just in Kenya, but all over Africa. Economic growth rates are at historic highs and democratization appears finally to be taking root. The question emerges: Will Africa be the world’s next development miracle?

More here.

Malcolm Gladwell in The New Yorker:

One of the most important tools in contemporary educational research is “value added” analysis. It uses standardized test scores to look at how much the academic performance of students in a given teacher’s classroom changes between the beginning and the end of the school year. Suppose that Mrs. Brown and Mr. Smith both teach a classroom of third graders who score at the fiftieth percentile on math and reading tests on the first day of school, in September. When the students are retested, in June, Mrs. Brown’s class scores at the seventieth percentile, while Mr. Smith’s students have fallen to the fortieth percentile. That change in the students’ rankings, value-added theory says, is a meaningful indicator of how much more effective Mrs. Brown is as a teacher than Mr. Smith.

One of the most important tools in contemporary educational research is “value added” analysis. It uses standardized test scores to look at how much the academic performance of students in a given teacher’s classroom changes between the beginning and the end of the school year. Suppose that Mrs. Brown and Mr. Smith both teach a classroom of third graders who score at the fiftieth percentile on math and reading tests on the first day of school, in September. When the students are retested, in June, Mrs. Brown’s class scores at the seventieth percentile, while Mr. Smith’s students have fallen to the fortieth percentile. That change in the students’ rankings, value-added theory says, is a meaningful indicator of how much more effective Mrs. Brown is as a teacher than Mr. Smith.

It’s only a crude measure, of course. A teacher is not solely responsible for how much is learned in a classroom, and not everything of value that a teacher imparts to his or her students can be captured on a standardized test. Nonetheless, if you follow Brown and Smith for three or four years, their effect on their students’ test scores starts to become predictable: with enough data, it is possible to identify who the very good teachers are and who the very poor teachers are. What’s more—and this is the finding that has galvanized the educational world—the difference between good teachers and poor teachers turns out to be vast.

Eric Hanushek, an economist at Stanford, estimates that the students of a very bad teacher will learn, on average, half a year’s worth of material in one school year. The students in the class of a very good teacher will learn a year and a half’s worth of material. That difference amounts to a year’s worth of learning in a single year. Teacher effects dwarf school effects: your child is actually better off in a “bad” school with an excellent teacher than in an excellent school with a bad teacher. Teacher effects are also much stronger than class-size effects. You’d have to cut the average class almost in half to get the same boost that you’d get if you switched from an average teacher to a teacher in the eighty-fifth percentile. And remember that a good teacher costs as much as an average one, whereas halving class size would require that you build twice as many classrooms and hire twice as many teachers.

More here.

Steve Coates in the New York Times:

You have to admire a scholar who can produce a small library of erudite, elegant and accessible books on American history, the New Testament and his own powerful brand of Roman Catholicism, winning a Pulitzer Prize along the way. And you have to be impressed by a plucky Spanish provincial, in the dangerous days of Nero and Domitian, who could manage to earn a handsome living writing dirty poems for the urban sophisticates of ancient Rome. But can you condone what they get up to under a single set of covers? “Martial’s Epigrams,” Garry Wills’s enthusiastic verse translations of Marcus Valerius Martialis, Rome’s most anatomically explicit poet, offers a chance to find out.

You have to admire a scholar who can produce a small library of erudite, elegant and accessible books on American history, the New Testament and his own powerful brand of Roman Catholicism, winning a Pulitzer Prize along the way. And you have to be impressed by a plucky Spanish provincial, in the dangerous days of Nero and Domitian, who could manage to earn a handsome living writing dirty poems for the urban sophisticates of ancient Rome. But can you condone what they get up to under a single set of covers? “Martial’s Epigrams,” Garry Wills’s enthusiastic verse translations of Marcus Valerius Martialis, Rome’s most anatomically explicit poet, offers a chance to find out.

The pairing is not as counterintuitive as one might imagine. Wills, who has a Ph.D. in classics and who once taught ancient Greek at Johns Hopkins, has long kept a foot in the ancient world. His Pulitzer winner, “Lincoln at Gettysburg,” brilliantly analyzed Lincoln’s greatest speech in terms of the conventions of ancient Greek funeral orations, and he has also translated the Latin of St. Augustine’s “Confessions.”

Martial, though, was no saint. Arriving in Rome around A.D. 64, he spent much of the next four decades composing short topical verse about life in the big city, an urban panorama as broad, as varied and as full of depraved humanity as any to have survived from classical times.

More here.

///

Adam's Complaint

Denise Levertov

Some people,

no matter what you give them,

still want the moon.

The bread,

the salt,

white meat and dark,

still hungry.

The marriage bed

and the cradle,

still empty arms.

You give them land,

their own earth under their feet,

still they take to the roads.

And water: dig them the deepest well,

still it's not deep enough

to drink the moon from.

.

Christopher Hitchens in The Atlantic Monthly:

The thumbnail social history of the United States, as Godfrey Hodgson (the author of America in Our Time) once phrased it to me, is as follows: agrarian population moves as soon as it can to the cities, and then consummates the process by evacuating the cities for the suburbs. More Americans now live in the suburbs than anywhere else, and more do so by choice. Anachronisms of two kinds persist in respect of this phenomenon. The first is the apparently unshakable belief of political candidates that they will sound better, and appear more authentic, if they can claim to come from a small town (something we were almost spared this year, until the chiller from Wasilla). The second is the continued stern disapproval of anything “suburban” by the strategic majority of our country's intellectuals. The idiocy of rural life? If you must. The big city? All very well. Bohemia, or perhaps Paris or Prague? Yes indeed. The suburbs? No thank you.

The thumbnail social history of the United States, as Godfrey Hodgson (the author of America in Our Time) once phrased it to me, is as follows: agrarian population moves as soon as it can to the cities, and then consummates the process by evacuating the cities for the suburbs. More Americans now live in the suburbs than anywhere else, and more do so by choice. Anachronisms of two kinds persist in respect of this phenomenon. The first is the apparently unshakable belief of political candidates that they will sound better, and appear more authentic, if they can claim to come from a small town (something we were almost spared this year, until the chiller from Wasilla). The second is the continued stern disapproval of anything “suburban” by the strategic majority of our country's intellectuals. The idiocy of rural life? If you must. The big city? All very well. Bohemia, or perhaps Paris or Prague? Yes indeed. The suburbs? No thank you.

The achievement of Richard Yates's Revolutionary Road was to anatomize the ills and woes of suburbia while simultaneously satirizing those suburbanites and others who thought that they themselves were too good for the 'burbs.

More here.

Wendy O'Shea-Meddour in the International Literary Quarterly:

Of Pakistan, we are told:

The local people would hardly be there, in their own land, or would be there only as ciphers swept aside by the agents of the faith. It is a dreadful mangling of history. It is a convert’s view; that is all that can be said for it. History has become a kind of neurosis. Too much has to be ignored or angled; there is too much fantasy. This fantasy isn’t in the books alone; it affects people’s lives. (329)

Islam is found guilty of inducing mental illness on a national scale because it is an “Arab” religion with sacred places in Arab lands. According to this peculiar thesis, Arabs do not suffer from neurosis because they are not “converts.” The narrator fails to mention that Arabs were generally polytheists at the time of the prophet Muhammad and in order to become Muslim necessarily “converted.” Perhaps this point is dismissed because the narrator believes that the ‘sacred places” of Arabs are “in their own lands”? Assuming that this is the reasoning, it would follow that European and American Christians and Jews suffer from a similar “neurosis” because their “sacred places” are abroad. However, it is clear that in the narrator’s opinion, Western Christians and Jews are mentally sound. The logic behind Naipaul’s argument is impossible to follow. As Eqbal Ahmed asks,

Islam is found guilty of inducing mental illness on a national scale because it is an “Arab” religion with sacred places in Arab lands. According to this peculiar thesis, Arabs do not suffer from neurosis because they are not “converts.” The narrator fails to mention that Arabs were generally polytheists at the time of the prophet Muhammad and in order to become Muslim necessarily “converted.” Perhaps this point is dismissed because the narrator believes that the ‘sacred places” of Arabs are “in their own lands”? Assuming that this is the reasoning, it would follow that European and American Christians and Jews suffer from a similar “neurosis” because their “sacred places” are abroad. However, it is clear that in the narrator’s opinion, Western Christians and Jews are mentally sound. The logic behind Naipaul’s argument is impossible to follow. As Eqbal Ahmed asks,

Who is not a convert? By Naipaul’s definition, if Iranians are converted Muslims, then Americans are converted Christians, the Japanese are converted Buddhists, and the Chinese, large numbers of them, are converted Buddhists as well. Everybody is converted because at the beginning every religion had only a few followers. Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Judaism, all prophetic religions developed through conversion. In that sense, his organising thesis should not exclude anyone. (Ahmad 9-10)

More here.

My face is symmetrical. Therefore, the situation is completely resolved. My voice is melodious and, when not utterly aloof, slightly flirtatious. My posture, walk, and way of slowly shifting my weight from one hip to the other while twirling my hair absentmindedly as I gaze off into an untroubled haze are all compelling as hell to ruminate upon, in silent contemplation, while the rest of the world pauses. I even smell great. You’re in for a rare treat, sensory-input-wise, being around me. Go ahead. Soak it in. Feast your eyes. This is one of those moments. For you. So you see, we have no cause for distress anymore, in terms of whatever that may have been that was temporarily impeding the immediate gratification of my every wish.

more from The Onion here.

If he were less shy and had a funny accent, David Plouffe would be every bit the household name that James Carville is—perhaps even going on Oprah and taking cameo roles in Hollywood movies. Plouffe is, after all, “the unsung hero” of the “best political campaign in the history of the United States of America”—which is how Barack Obama described him before a global television audience, in the mother of all shout-outs, on the night he was elected Leader of the Free World. At 41, Plouffe (rhymes with “no fluff”) will probably never top his historic achievement of managing the campaign that gave this nation its first African-American commander in chief. The juggernaut Plouffe led, which grew to a payroll of 5,000 before Election Day, raised record amounts of cash from millions of small donors, defeated the once-invincible Hillary Clinton machine, and crushed the flailing Republican nominee, John McCain. Obama’s success was so overwhelming that it’s hard to remember those early days when the freshman senator from Illinois was the longest of long-shots and the darkest of dark horses in a country still troubled by issues of race.

more from Portfolio here.

Saturday, December 13, 2008

Greg Beato in Reason:

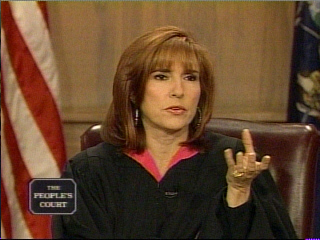

Five years ago, there were seven fake judges giving us our day (and occasional evening hour) in court. Now there are nearly twice that many, with three new shows (Judge Karen, Judge Jeanine Pirro, and Family Court With Judge Penny) debuting in September 2008 alone. At least one other, Street Judge, is on the way. They're there because in the ever-shrinking world of television syndication, where competition from cable and the Internet has made Oprah-sized hits as rare as silk ascots on The Jerry Springer Show, the new dream is a steady 1.5 Nielsen rating on a weekly budget of no more than $500,000. Justice porn, it turns out, is a fairly reliable way to achieve that end: Find a sassy real-life jurist with an itch for the big time, throw some penny-ante miscreants at her mercy, and let the premature adjudication begin.

Five years ago, there were seven fake judges giving us our day (and occasional evening hour) in court. Now there are nearly twice that many, with three new shows (Judge Karen, Judge Jeanine Pirro, and Family Court With Judge Penny) debuting in September 2008 alone. At least one other, Street Judge, is on the way. They're there because in the ever-shrinking world of television syndication, where competition from cable and the Internet has made Oprah-sized hits as rare as silk ascots on The Jerry Springer Show, the new dream is a steady 1.5 Nielsen rating on a weekly budget of no more than $500,000. Justice porn, it turns out, is a fairly reliable way to achieve that end: Find a sassy real-life jurist with an itch for the big time, throw some penny-ante miscreants at her mercy, and let the premature adjudication begin.

Explicitly moral, obscenely didactic, showcasing a perversely distorted view of the American legal system, justice porn is a potent, ubiquitous presence in our lives, and at least as influential as the cartoon mayhem of Saints Row 2 or Young Jeezy's latest ode to thug life. And yet has the Federal Communications Commission's airwave fresheners ever knitted their vigilant brows over Judge Judy's contempt for the petitioners who enter her chambers seeking some facsimile of fairness? Will Hillary Clinton ever make alarmist speeches about the way these shows desensitize viewers to due process while glorifying judicial misconduct? When will the obsessive-compulsive filth inspectors at the Parents Television Council record every act of gratuitous gavel banging that occurs on these shows over a two-week period? Don't they know that grown-ups—naive and malleable grown-ups with a natural curiosity about civil litigation—are watching?

More here.

Ethan A. Nadelmann in the Wall Street Journal:

Today is the 75th anniversary of that blessed day in 1933 when Utah became the 36th and deciding state to ratify the 21st amendment, thereby repealing the 18th amendment. This ended the nation's disastrous experiment with alcohol prohibition.

Today is the 75th anniversary of that blessed day in 1933 when Utah became the 36th and deciding state to ratify the 21st amendment, thereby repealing the 18th amendment. This ended the nation's disastrous experiment with alcohol prohibition.

It's already shaping up as a day of celebration, with parties planned, bars prepping for recession-defying rounds of drinks, and newspapers set to publish cocktail recipes concocted especially for the day.

But let's hope it also serves as a day of reflection. We should consider why our forebears rejoiced at the relegalization of a powerful drug long associated with bountiful pleasure and pain, and consider too the lessons for our time.

The Americans who voted in 1933 to repeal prohibition differed greatly in their reasons for overturning the system. But almost all agreed that the evils of failed suppression far outweighed the evils of alcohol consumption.

The change from just 15 years earlier, when most Americans saw alcohol as the root of the problem and voted to ban it, was dramatic. Prohibition's failure to create an Alcohol Free Society sank in quickly. Booze flowed as readily as before, but now it was illicit, filling criminal coffers at taxpayer expense.

More here.

The twentieth century left deep and unhealed wounds in the memory of almost all the nations of eastern and central Europe, with its revolutions, uprisings, two World Wars, the Nazi occupation, the inconceivable horror of the Holocaust. Then there was the huge number of local wars and conflicts, most of which had a pronounced national flavour: tin he Baltic States, Poland, western Ukraine and the Balkans. We witnessed a string of dictatorships of different ilk, each unceremoniously depriving people of their civic and political liberty, foisting upon them instead a standard system of values binding on all. National independence was in succession gained and lost, and gained again, with this for the most part being seen within the framework of ethnic self-identification. And each time, this or that community felt insulted and humiliated. This is our shared history. Yet each national group remembers and perceives it’s own history in its own way. National memory refashions and interprets this shared history in its own way. For this reason, each national group has its own twentieth century.

more from Eurozine here.

In 1868, at the age of 23, Gerard Manley Hopkins decided to burn the poetry he’d written up to that time: “Slaughter of the Innocents,” he noted in his journal. Recognizing that poetry depended on deep and perhaps dangerous feeling — and given what he would later concede was a disturbing affinity with Walt Whitman (“a very great scoundrel”) — Hopkins decided it was incompatible with his calling to the Jesuit priesthood. In that capacity Hopkins would persevere amid ghastly privations, though he could not entirely escape his destiny as one of the most influential poets of the 20th century (a century he would not live to see). As Paul Mariani points out in “Gerard Manley Hopkins,” his generous new biography, the “unpromising beginnings” of Hopkins’s prosodic revolution were in a Jesuit classroom in London, where as a teacher of rhetoric he tried to impart something of his enthusiasm for the later rhythms of Milton and the alliterative effects of the Anglo-Saxons.

more from the NY Times here.

In April, 1951, Richard Yates sailed from New York to Paris. He had been there twice before, as a child and, later, as a soldier, but for him, as for so many American writers, it was less a place than a laurelled idea—the silvery and careless city of Hemingway and Fitzgerald. Careless, but a literary workshop, too: Yates said that he was determined to produce short stories there “at the rate of about one a month.” Then twenty-five years old, he was beginning an indenture that would last until his death, in 1992. Around the compulsion of writing he shaped everything else. There were two other compulsions, smoking and drinking, but they only killed him, while writing plainly kept him alive. (He was an alcoholic, but he rarely wrote while drunk.) He lived in New York, in Iowa, in Los Angeles, in Boston, and, finally, in Alabama, yet his homes were identical in their shabby discipline of neglect. In each there was a table for writing, a circle of crushed cockroaches around the desk chair, curtains made colorless by cigarette smoke, a few books, and nothing much in the kitchen but coffee, bourbon, and beer. Friends and colleagues found these accommodations appallingly bleak; for Yates they were accommodations for writing.

more from The New Yorker here.

LORRAINE ADAMS reviews The Jewel of Medina by Sherry Jones in The New York Times:

Sherry Jones, a Montana and Idaho correspondent for the Bureau of National Affairs, a specialty news service covering legislative and regulatory issues, has written a novel from the point of view of Muhammad’s third and youngest wife, A’isha. Most accounts agree that she was 6 at their engagement, 9 at their wedding and 14 when publicly accused of adultery. The novel’s story line coincides with a pivotal time in Islamic history — the 10 years beginning with Muhammad’s flight from Mecca to Medina in A.D. 622 and ending with his death at age 62. His actions during that period have also been seized upon by Western commentators and poets as proof of Muhammad’s unmanageable sexual appetite and self-serving declaration of divine revelation. Among the most contested criticisms of Muhammad are his taking of many more than the four wives he decreed as the limit for other men and his edict, supposedly inspired by Allah, requiring his wives to be placed behind a curtain, the basis for the veiling of Muslim women. Both matters are fictionalized in Jones’s novel, which was scheduled to be published by the Random House imprint Ballantine until controversy intervened.

Sherry Jones, a Montana and Idaho correspondent for the Bureau of National Affairs, a specialty news service covering legislative and regulatory issues, has written a novel from the point of view of Muhammad’s third and youngest wife, A’isha. Most accounts agree that she was 6 at their engagement, 9 at their wedding and 14 when publicly accused of adultery. The novel’s story line coincides with a pivotal time in Islamic history — the 10 years beginning with Muhammad’s flight from Mecca to Medina in A.D. 622 and ending with his death at age 62. His actions during that period have also been seized upon by Western commentators and poets as proof of Muhammad’s unmanageable sexual appetite and self-serving declaration of divine revelation. Among the most contested criticisms of Muhammad are his taking of many more than the four wives he decreed as the limit for other men and his edict, supposedly inspired by Allah, requiring his wives to be placed behind a curtain, the basis for the veiling of Muslim women. Both matters are fictionalized in Jones’s novel, which was scheduled to be published by the Random House imprint Ballantine until controversy intervened.

The most authoritative contemporary English-language account of A’isha — “Politics, Gender, and the Islamic Past: The Legacy of A’isha Bint Abi Bakr” — is not listed as one of Jones’s sources. But its author, Denise Spellberg, played a role in Random House’s decision to abandon the book.

More here.

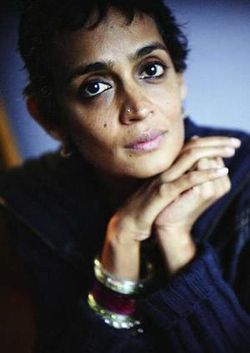

Arundhati Roy in The Guardian:

We've forfeited the rights to our own tragedies. As the carnage in Mumbai raged on, day after horrible day, our 24-hour news channels informed us that we were watching “India's 9/11”. Like actors in a Bollywood rip-off of an old Hollywood film, we're expected to play our parts and say our lines, even though we know it's all been said and done before. As tension in the region builds, US Senator John McCain has warned Pakistan that if it didn't act fast to arrest the “Bad Guys” he had personal information that India would launch air strikes on “terrorist camps” in Pakistan and that Washington could do nothing because Mumbai was India's 9/11. But November isn't September, 2008 isn't 2001, Pakistan isn't Afghanistan and India isn't America. So perhaps we should reclaim our tragedy and pick through the debris with our own brains and our own broken hearts so that we can arrive at our own conclusions.

We've forfeited the rights to our own tragedies. As the carnage in Mumbai raged on, day after horrible day, our 24-hour news channels informed us that we were watching “India's 9/11”. Like actors in a Bollywood rip-off of an old Hollywood film, we're expected to play our parts and say our lines, even though we know it's all been said and done before. As tension in the region builds, US Senator John McCain has warned Pakistan that if it didn't act fast to arrest the “Bad Guys” he had personal information that India would launch air strikes on “terrorist camps” in Pakistan and that Washington could do nothing because Mumbai was India's 9/11. But November isn't September, 2008 isn't 2001, Pakistan isn't Afghanistan and India isn't America. So perhaps we should reclaim our tragedy and pick through the debris with our own brains and our own broken hearts so that we can arrive at our own conclusions.

It's odd how in the last week of November thousands of people in Kashmir supervised by thousands of Indian troops lined up to cast their vote, while the richest quarters of India's richest city ended up looking like war-torn Kupwara – one of Kashmir's most ravaged districts. The Mumbai attacks are only the most recent of a spate of terrorist attacks on Indian towns and cities this year. Ahmedabad, Bangalore, Delhi, Guwahati, Jaipur and Malegaon have all seen serial bomb blasts in which hundreds of ordinary people have been killed and wounded. If the police are right about the people they have arrested as suspects, both Hindu and Muslim, all Indian nationals, it obviously indicates that something's going very badly wrong in this country.

More here.

Merit Award: Majed Sultan Ali, Kuwait City, Kuwait

Nikon Coolpix Digital Camera and a Bogen National Geographic Prize Package

Majed Sultan Ali, a computer engineer, photographed a wild cat in Kuwait's Subah reserve. Noticing flying ants in the area, he waited for one to enter the frame before shooting. (Nikon D300 camera, Nikkor 200-400 mm Vr lens at 400 mm, exposure at 1/640 second, f/5.6, ISO 320)

Again this year, Traveler partnered with Photo District News on the ultimate travel-photo contest. More than 4,000 amateur shutterbugs entered 14,647 images in our World in Focus competition.

More here. [Thanks to Marilyn Terrell.]

Martti Ahtisaari's Nobel Peace Prize Lecture:

Peace is a question of will. All conflicts can be settled, and there are no excuses for allowing them to become eternal. It is simply intolerable that violent conflicts defy resolution for decades causing immeasurable human suffering, and preventing economic and social development. The passivity and impotence of the international community make it more difficult for us to place our faith in jointly built security structures. Despite the many challenges, even the most intractable conflicts can be resolved if the parties involved and the international community join forces and work together for a common aim. The United Nations provides the right framework for international peace efforts and solutions to global problems. However, we are all aware of the constraints of the United Nations and of the tendency of the member states to give it demanding assignments without providing adequate resources and political support. It is important that the UN member states work resolutely to strengthen the world organization. We cannot afford to lose the UN.

Peace is a question of will. All conflicts can be settled, and there are no excuses for allowing them to become eternal. It is simply intolerable that violent conflicts defy resolution for decades causing immeasurable human suffering, and preventing economic and social development. The passivity and impotence of the international community make it more difficult for us to place our faith in jointly built security structures. Despite the many challenges, even the most intractable conflicts can be resolved if the parties involved and the international community join forces and work together for a common aim. The United Nations provides the right framework for international peace efforts and solutions to global problems. However, we are all aware of the constraints of the United Nations and of the tendency of the member states to give it demanding assignments without providing adequate resources and political support. It is important that the UN member states work resolutely to strengthen the world organization. We cannot afford to lose the UN.

In a conflict, one party can always claim victory, but building peace must involve everybody: the weak and the powerful, the victors and the vanquished, men and women, young and old. However, peace negotiations are often conducted by a small elite. In the future we must be better able to achieve a broader participation in peace processes. Particularly, there is a need to ensure the engagement of women in all stages of a peace process.

Peace processes and the agreements resulting from them end the violence. But the real work only starts after a peace agreement has been concluded. The agreements reached have to be implemented. Social and political change does not happen overnight, and the reconstruction and establishment of democracy demand patience. That requires a comprehensive approach to peacebuilding, and support for civil society.

More here.

I have visited Busia every year since 1997 to help local development-oriented nonprofit organizations design and evaluate their rural programs. In so doing, I have been exposed to impressive changes that are mirrored throughout the country. Kenyan economic growth rates surged between 2002 and 2007, achieving levels not seen since the 1970s. Last summer Nairobi’s never-ending traffic jams of imported Japanese cars were but one tangible indication that Kenyans were suddenly on the move. Construction projects were everywhere, as developers took advantage of the unexpected spike in land values. New productive sectors, like same-day cut flower exports to Europe, employed tens of thousands of workers. Like a fever that had suddenly broken, the resignation and fear of the 1990s were replaced by energy, optimism, and a feeling that there was no time to lose.