Barack Obama in the Washington Post:

By now, it's clear to everyone that we have inherited an economic crisis as deep and dire as any since the days of the Great Depression. Millions of jobs that Americans relied on just a year ago are gone; millions more of the nest eggs families worked so hard to build have vanished. People everywhere are worried about what tomorrow will bring.

By now, it's clear to everyone that we have inherited an economic crisis as deep and dire as any since the days of the Great Depression. Millions of jobs that Americans relied on just a year ago are gone; millions more of the nest eggs families worked so hard to build have vanished. People everywhere are worried about what tomorrow will bring.

What Americans expect from Washington is action that matches the urgency they feel in their daily lives — action that's swift, bold and wise enough for us to climb out of this crisis.

Because each day we wait to begin the work of turning our economy around, more people lose their jobs, their savings and their homes. And if nothing is done, this recession might linger for years. Our economy will lose 5 million more jobs. Unemployment will approach double digits. Our nation will sink deeper into a crisis that, at some point, we may not be able to reverse.

That's why I feel such a sense of urgency about the recovery plan before Congress. With it, we will create or save more than 3 million jobs over the next two years, provide immediate tax relief to 95 percent of American workers, ignite spending by businesses and consumers alike, and take steps to strengthen our country for years to come.

More here.

///

Sadie and Maud

Gwendolyn Brooks

Maud went to college.

Sadie stayed home.

Sadie scraped life

With a fine toothed comb.

She didn't leave a tangle in

Her comb found every strand.

Sadie was one of the livingest chicks

In all the land.

Sadie bore two babies

Under her maiden name.

Maud and Ma and Papa

Nearly died of shame.

When Sadie said her last so-long

Her girls struck out from home.

(Sadie left as heritage

Her fine-toothed comb.)

Maud, who went to college,

Is a thin brown mouse.

She is living all alone

In this old house.

///

From The Root:

When author and history professor Carter G. Woodson created what would become Black History Month in February 1926, America’s black citizens were on the outside looking in, spectators to the great American drama, subjected to a repression of aspiration and identity so severe that it amounted to domestic apartheid. Lynchings were so common that the NAACP kept a flag at its New York offices to announce that “A Man Was Lynched Yesterday.” The flag flew often. The Great Migration was well underway. Black citizens moved from the southern states to the North and Midwest by the millions, and African-American voting was suppressed, sometimes violently, especially in the Jim Crow South. Woodson, grasping the enormity of the situation, created “Negro History Week” as a way of highlighting the social contributions of black Americans.

When author and history professor Carter G. Woodson created what would become Black History Month in February 1926, America’s black citizens were on the outside looking in, spectators to the great American drama, subjected to a repression of aspiration and identity so severe that it amounted to domestic apartheid. Lynchings were so common that the NAACP kept a flag at its New York offices to announce that “A Man Was Lynched Yesterday.” The flag flew often. The Great Migration was well underway. Black citizens moved from the southern states to the North and Midwest by the millions, and African-American voting was suppressed, sometimes violently, especially in the Jim Crow South. Woodson, grasping the enormity of the situation, created “Negro History Week” as a way of highlighting the social contributions of black Americans.

When Barack Obama took the oath of office to become the 44th president of the United States on Jan. 20, he did so as the beneficiary of the broadest, most sweeping black vote in American history. Since 1976, February has been officially designated as Black History Month, but the inauguration of the nation's first black president underscored just how much the climate that produced Woodson’s noble idea had changed. Some say the need for Black History Month has ended altogether. Black History Month has become more or less a reflex in American life, with many observances reduced to rote and repetitious rituals. Many of those observances seem to be as much about marketing products as they are about the collective national memory.

More here.

From Brainyquotes:

I didn't know I was a slave until I found out I couldn't do the things I wanted.

I didn't know I was a slave until I found out I couldn't do the things I wanted.

Frederick Douglass

I prayed for twenty years but received no answer until I prayed with my legs.

Frederick Douglass

I prefer to be true to myself, even at the hazard of incurring the ridicule of others, rather than to be false, and to incur my own abhorrence.

Frederick Douglass

If there is no struggle, there is no progress.

Frederick Douglass

It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.

Frederick Douglass

It is not light that we need, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake.

Frederick Douglass

Man's greatness consists in his ability to do and the proper application of his powers to things needed to be done.

Frederick Douglass

No man can put a chain about the ankle of his fellow man without at last finding the other end fastened about his own neck.

Frederick Douglass

One and God make a majority.

Frederick Douglass

People might not get all they work for in this world, but they must certainly work for all they get.

Frederick Douglass

Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.

Frederick Douglass

Slaves are generally expected to sing as well as to work.

Frederick Douglass

More here.

From the New York Review of Books:

On the eve of the war in Gaza, Robert Malley and Hussein Agha wrote “How Not to Make Peace in the Middle East” [NYR, January 15], a critical review of US policies in the region during the Clinton and Bush years, and a call for a new approach. On January 24, a few days after the end of the conflict, Malley spoke to Hugh Eakin about its consequences. Following are excerpts of the interview, which is available in full at www.nybooks.com/podcasts.

On the eve of the war in Gaza, Robert Malley and Hussein Agha wrote “How Not to Make Peace in the Middle East” [NYR, January 15], a critical review of US policies in the region during the Clinton and Bush years, and a call for a new approach. On January 24, a few days after the end of the conflict, Malley spoke to Hugh Eakin about its consequences. Following are excerpts of the interview, which is available in full at www.nybooks.com/podcasts.

Hugh Eakin: In Gaza, does Hamas retain the ability to govern?

Robert Malley: All the reporting we've been getting, both during and after the war, is that, for all the massive destruction and the large number of victims, Hamas's authority has not been eroded. They have reasserted it, sometimes ruthlessly, since the end of the war. They are back, policing the streets. Of course, they don't have the same means they had in terms of police stations, and basic infrastructure of government. But in terms of asserting authority, there is really no political alternative today in Gaza that could challenge Hamas. And so if the objective of the war was to weaken Hamas's grip on Gaza, that failed.

H.E.: Should the US have contact with Hamas?

R.M.: I've never advocated direct engagement with Hamas, because we know the political realities here. My argument is different. What I say is that we have to start from a factual realization that the policies of the last two years have not only failed to achieve their objectives. They often produced the precise opposite of what we sought to promote.

More here.

Howard Gardner in Slate:

A thought experiment. You walk into a bookstore and see three stacks of books. The books are titled Born To Be Good, Born To Be Bad, and Born To Be Good or Bad. Which one do you pick up first? Fast forward. You have now scanned the tables of contents of the three books. The first book has chapters called “Smile,” “Love,” and “Compassion”; the second features chapters titled “Anger,” “Jealousy,” and “Spite”; the third has chapters on “Love vs. Hate,” “Altruism vs. Selfishness,” and “Honesty vs. “Deceit.” Which book do you buy? Which are you apt to believe?”

A thought experiment. You walk into a bookstore and see three stacks of books. The books are titled Born To Be Good, Born To Be Bad, and Born To Be Good or Bad. Which one do you pick up first? Fast forward. You have now scanned the tables of contents of the three books. The first book has chapters called “Smile,” “Love,” and “Compassion”; the second features chapters titled “Anger,” “Jealousy,” and “Spite”; the third has chapters on “Love vs. Hate,” “Altruism vs. Selfishness,” and “Honesty vs. “Deceit.” Which book do you buy? Which are you apt to believe?”

Dacher Keltner, a psychologist at University of California, Berkeley, and the director of the Greater Good Science Center there, is banking on an interest in a Rousseauian rather than Hobbesian view of human nature. In Born To Be Good, he argues that we are born as miniature angels, rather than marked by original sin. But presuming that readers have no patience for romantic mush, his subtitle—The Science of a Meaningful Life—promises hardheadedness, not faith or folklore.

More here.

Emily Wax in the Washington Post:

Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa proclaimed Wednesday that the rebel Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam would be “completely defeated in a few days,” potentially signaling an end to a 25-year insurgency that is one of the world's longest ongoing conflicts.

Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa proclaimed Wednesday that the rebel Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam would be “completely defeated in a few days,” potentially signaling an end to a 25-year insurgency that is one of the world's longest ongoing conflicts.

The rebels' last holdouts are penned in a small zone in the north of the island nation, and government forces say they are confident that they are close to crushing the insurgency. Analysts, however, say guerrilla fighting might persist for months.

Civilian casualties have been significant: U.N. officials said that 52 civilians were killed in the past day in one sector and that cluster bombs had struck a hospital.

More here. It is also worth (re)reading Ram Manikkalingam's analysis of the conflict written for 3QD a few months ago: What I have learned from being a part of Sri Lanka’s Civil War.

Wednesday, February 4, 2009

Over at Public Ethics Radio:

Today on Public Ethics Radio, we discuss the role that civilian casualties play in assessing the justice of war.

For a war to be just, it must satisfy what is known as the proportionality principle. In a disproportionate war, the harms caused by going to war are so evil that they outweigh the benefits of an otherwise worthy goal. Considerations of proportionality are also relevant to the assessment of particular tactics undertaken in an ongoing war.

To help us understand how this weighing of harms and benefits works, we spoke to the distinguished just war scholar Jeff McMahan. McMahan is a Professor of Philosophy at Rutgers University. He has published widely on just war theory and defensive violence, and many of his articles are available through his website. His recent views on proportionality are discussed in, among others, his essay, “Just Cause for War.”

Click here to download the episode (28:17, 12.9 mb, mp3), or click on the online media player below. You can also download the transcript.

1972 was a difficult year for the novel. This might—and perhaps should—be said of all years and times, since the novel is forever, genetically, finding everything a struggle and all things difficult (I think we’re supposed to be worried when the novel does not do this). But 1972 was particularly special in its overshadowing, domineering, mattering way. It was a year that refused to cede an inch to the make-believe. The merely imaginary might finally have seemed trifling up against some of the defining and grisly moments of the century that collided that year and chewed up every available dose of attention in the culture. 1972, in short, produced the Watergate scandal, the Munich Massacre, and Bloody Sunday. Nixon traveled to China in 1972, and the last U.S. troops finally departed Vietnam. It wasn’t clear that a novel had leverage against all of this atrocity, deceit, transgression, and milestone, let alone a novel posing as a ship’s log, narrated by a widowed ship slave who has witnessed logic-defying architecture, radical ecological invention, and faked a pregnancy while being banished—by her alcoholic, abusive husband—from all land and humanity. Forget that painting (or sculpture, or the better poetry) was never asked to compete with the news, or to be the news. The novel’s weird burden of relevance—to reflect and anticipate the times, to grab headlines, to be somehow current, while not also disgracing the language—was being shirked all over the place, and Stanley Crawford, already unusually capable of uncoiling his brain and repacking it in his head in a new, gnarled design for every book he wrote, was chief among those writers who seemed siloed in a special, ahistorical field, working with private alchemical tools, producing work just out of tune enough to disrupt the flight of the birds that passed his hideout.

more from Context here.

Take a deep breath and prepare to sweep away all the jargon and highfalutin that has built up around Ingeborg Bachmann and Paul Celan over the years. It’s a unique opportunity to start from scratch. The legendary correspondence between Ingeborg Bachmann and Paul Celan which was originally intended to be kept under wraps until 2023, has been released by their heirs and edited by Suhrkamp Verlag with appropriate thoroughness. And here they are – almost 200 documents, letters, dedications, telegrams, postcards which open the door onto a huge, difficult relationship between two individuals, who were nothing less than hurled into each others’ arms by affinity, poetic calling, erotic attraction and mourning for events of the past. The documents date from the period before fame towered over the two poets in a way that seemed more destructive than protective. Indeed the need for protection and the feeling of woundedness thread through their letters like a leitmotif.

more from Sign and Sight here.

He was born in 1897, the same year as William Faulkner, a year after F. Scott Fitzgerald, and two years before Hemingway; he published his first novel in 1926, the same year as Soldiers’ Pay and The Sun Also Rises, a year after The Great Gatsbyand Arrowsmith, and a year before Elmer Gantry, and was immediately hailed as one of the best writers of his generation. He went on to write several more novels, almost all of them critically acclaimed bestsellers, and to win three Pulitzer Prizes, one for fiction and two for drama (he is still the only writer to have won Pulitzers in both categories). One of his novels was among the twentieth century’s great publishing sensations; one of his plays is the most performed American theatrical work of all time; yet another of his stage efforts was the basis for one of the most successful Broadway musicals in history. Some consider him the equal or superior of Hemingway and Fitzgerald as a novelist, and some place him alongside—or above—Eugene O’Neill and Tennessee Williams in the pantheon of American drama. Why, then, can it seem as if Thornton Wilder has fallen between the cracks?

link to the pdf at Hudson Review here.

Our own Morgan Meis in The Smart Set:

Updike gave a lecture on American art last year at the National Endowment for the Humanities. It was called “The Clarity of Things: What is American about American Art.” Updike discussed how American painting finally managed to become American. Most of the early American painters were tradesman. They knew how to paint, but they didn't know how to be “painterly.” As Updike put it, they were “liney” in the beginning.

Updike gave a lecture on American art last year at the National Endowment for the Humanities. It was called “The Clarity of Things: What is American about American Art.” Updike discussed how American painting finally managed to become American. Most of the early American painters were tradesman. They knew how to paint, but they didn't know how to be “painterly.” As Updike put it, they were “liney” in the beginning.

A line is a child’s first instrument of depiction, the boundary where one thing ends and another begins. The primitive artist is more concerned with what things are than what they look like to the eye’s camera. Lines serve the facts.

Liney is how you paint when you know how to render individual things but you don't have the skill to make the depth and perspective cohere into a scene, to blur some of the hard lines in order to create a work of art. Still, there was something about liney painting that was true to the American experience. Speaking about the liney paintings of mid-18th-century painter John Singleton Copley, Updike said, “In the art-sparse, mercantile world of the American colonies, Copley’s lavish literalism must have seemed fair dealing, a heaping measure of value paid in shimmering textures and scrupulously fine detail.” But as America developed, so did its painters. They wanted to be able to paint like the masters across the sea. As ever seems the case in America, they had mixed-up desires: They wanted to be just as good as the Europeans and yet uniquely American. So American painters had to learn the subtle lessons of the craft all over again. Aesthetic problems that, in Europe, had been tackled and resolved in the early Renaissance became contemporary. Eventually, the American painters found a way. During the 19th century, they started making paintings that could easily have been created by European masters but for the slightly rougher subject matter of an American wilderness largely untamed. In doing so, they gained in skill at the expense of their specific style. To become better painters, they had to stop being so American.

More here.

///

Omaha Beach

Piotr Florczyk

Returning here, it hasn't been easy

for them to find their place in the black sand—

always too much sun or rain,

strangers driving umbrellas yet deeper

into their land. The young radio host said so,

speaking of the vets. When the sea had come,

some curled up inside the shells;

others flexed and clicked their knuckles

on the trigger of each wave, forgetting

to come up for breath. Then as now, there was

no such a thing as fin-clapping fish,

quipped the host—his voice no more than

an umlaut going off the air. But he didn't

give us a name at the start or the end.

Nor did he explain how to rebury a pair of

big toes jutting out from the mud

at the water's edge. In the end, it's a fluke.

A beach ball gets lost. And a search

party leads us under the pier, into the frothy sea

impaling empty bottles on the rocks.

///

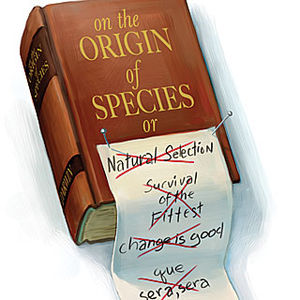

Michael Shermer in Scientific American:

On July 2, 1866, Alfred Russel Wallace, the co-discoverer of natural selection, wrote to Charles Darwin to lament how he had been “so repeatedly struck by the utter inability of numbers of intelligent persons to see clearly or at all, the self acting & necessary effects of Nat Selection, that I am led to conclude that the term itself & your mode of illustrating it, however clear & beautiful to many of us are yet not the best adapted to impress it on the general naturalist public.” The source of the misunderstanding, Wallace continued, was the name itself, in that it implies “the constant watching of an intelligent ‘chooser’ like man’s selection to which you so often compare it,” and that “thought and direction are essential to the action of ‘Natural Selection.’” Wallace suggested redacting the term and adopting Herbert Spencer’s phrase “survival of the fittest.”

On July 2, 1866, Alfred Russel Wallace, the co-discoverer of natural selection, wrote to Charles Darwin to lament how he had been “so repeatedly struck by the utter inability of numbers of intelligent persons to see clearly or at all, the self acting & necessary effects of Nat Selection, that I am led to conclude that the term itself & your mode of illustrating it, however clear & beautiful to many of us are yet not the best adapted to impress it on the general naturalist public.” The source of the misunderstanding, Wallace continued, was the name itself, in that it implies “the constant watching of an intelligent ‘chooser’ like man’s selection to which you so often compare it,” and that “thought and direction are essential to the action of ‘Natural Selection.’” Wallace suggested redacting the term and adopting Herbert Spencer’s phrase “survival of the fittest.”

Unfortunately, that is what happened, and it led to two myths about evolution that persist today: that there is a prescient directionality to evolution and that survival depends entirely on cutthroat competitive fitness.

More here.

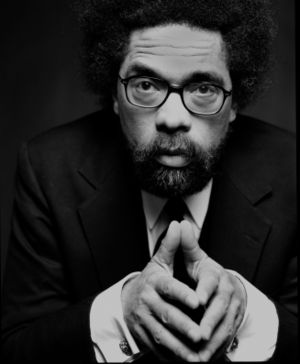

Note: This month, we will be posting daily items in honor of Black History Month:

From Wikipedia:

Cornel Ronald West (born June 2, 1953) is an American scholar, public intellectual, philosopher, critic, pastor, and civil rights activist. West currently serves as the Class of 1943 University Professor at Princeton University, where he teaches in the Center for African American Studies and in the department of Religion. West is known for his combination of political and moral insight and criticism, and his contribution to the post-1960s civil rights movement. The bulk of his work focuses upon the role of race, gender, and class in American society and the means by which people act and react to their “radical conditionedness”. West draws intellectual contributions from such diverse traditions as the African American Baptist Church, pragmatism and transcendentalism.

Cornel Ronald West (born June 2, 1953) is an American scholar, public intellectual, philosopher, critic, pastor, and civil rights activist. West currently serves as the Class of 1943 University Professor at Princeton University, where he teaches in the Center for African American Studies and in the department of Religion. West is known for his combination of political and moral insight and criticism, and his contribution to the post-1960s civil rights movement. The bulk of his work focuses upon the role of race, gender, and class in American society and the means by which people act and react to their “radical conditionedness”. West draws intellectual contributions from such diverse traditions as the African American Baptist Church, pragmatism and transcendentalism.

West was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma.[2] The grandson of a preacher, West marched as a young man in civil rights demonstrations and organized protests demanding black studies courses at his high school. West later wrote that, in his youth, he admired “the sincere black militancy of Malcolm X, the defiant rage of the Black Panther Party […] and the livid black theology of James Cone.” After graduating from John F. Kennedy High School in Sacramento, California, where he served as president of his high school class, he enrolled at Harvard University at age 17. He took classes from philosophers Robert Nozick and Stanley Cavell and graduated in three years, magna cum laude in Near Eastern Languages and Civilization in 1973. He was determined to press the university and its intellectual traditions into the service of his political agendas and not the other way around: to have its educational agendas imposed on him. “Owing to my family, church, and the black social movements of the 1960s”, he says, “I arrived at Harvard unashamed of my African, Christian, and militant de-colonized outlooks. More pointedly, I acknowledged and accented the empowerment of my black styles, mannerisms, and viewpoints, my Christian values of service, love, humility, and struggle, and my anti-colonial sense of self-determination for oppressed people and nations around the world.”

More here.

William Sieghart in The Times:

Who or what is Hamas, the movement that Ehud Barak, the Israeli Defence Minister, would like to wipe out as though it were a virus? Why did it win the Palestinian elections and why does it allow rockets to be fired into Israel? The story of Hamas over the past three years reveals how the Israeli, US and UK governments' misunderstanding of this Islamist movement has led us to the brutal and desperate situation that we are in now.

Who or what is Hamas, the movement that Ehud Barak, the Israeli Defence Minister, would like to wipe out as though it were a virus? Why did it win the Palestinian elections and why does it allow rockets to be fired into Israel? The story of Hamas over the past three years reveals how the Israeli, US and UK governments' misunderstanding of this Islamist movement has led us to the brutal and desperate situation that we are in now.

The story begins nearly three years ago when Change and Reform – Hamas's political party – unexpectedly won the first free and fair elections in the Arab world, on a platform of ending endemic corruption and improving the almost non-existent public services in Gaza and the West Bank. Against a divided opposition this ostensibly religious party impressed the predominantly secular community to win with 42 per cent of the vote.

Palestinians did not vote for Hamas because it was dedicated to the destruction of the state of Israel or because it had been responsible for waves of suicide bombings that had killed Israeli citizens. They voted for Hamas because they thought that Fatah, the party of the rejected Government, had failed them. Despite renouncing violence and recognising the state of Israel Fatah had not achieved a Palestinian state. It is crucial to know this to understand the supposed rejectionist position of Hamas.

More here. [Photo shows Hamas leader Khaled Meshal.]

Tuesday, February 3, 2009

Note: This month, we will be posting daily items in honor of Black History Month:

From Worldbook.com:

Before the American Civil War (1861-1865), many black writers were fugitive slaves. They described their experiences on plantations in an attempt to convince readers that slavery was immoral and to show the courage, humanity, and intelligence of the slaves. The most important slave autobiography of the period is the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845). Douglass became the leading spokesman for American blacks in the 1800's. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861), by Harriet Ann Jacobs, is the only autobiography about the unique hardships suffered by women slaves.

Before the American Civil War (1861-1865), many black writers were fugitive slaves. They described their experiences on plantations in an attempt to convince readers that slavery was immoral and to show the courage, humanity, and intelligence of the slaves. The most important slave autobiography of the period is the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845). Douglass became the leading spokesman for American blacks in the 1800's. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861), by Harriet Ann Jacobs, is the only autobiography about the unique hardships suffered by women slaves.

The first published African American fiction appeared in the mid-1800's. This fiction included such novels as Clotel, or The President's Daughter (1853), by William Wells Brown; and Our Nig (1859), by Harriet E. Wilson. They were similar in content to slave autobiographies. The Garies and Their Friends (1857), by Frank J. Webb, is a novel that describes the problems of a free family living in the North. Blake (1861-1862), by Martin Robinson Delany, is a novel about a free black man who organizes a slave rebellion.

After slavery was abolished in 1865, African American authors wrote in many literary forms to protest race discrimination. In the 1890's and early 1900's, Paul Laurence Dunbar was acclaimed for his romantic poems in black dialect. However, some of his verses imply bitter social criticism. Charles Waddell Chesnutt sought to revise the negative images of former slaves by portraying them as intelligent and resourceful in his realistic short stories and novels. Chesnutt is considered to be the first major African American writer of fiction. Such black women writers as Frances Harper and Pauline Hopkins challenged both racism and sexism in their novels.

More here.

From CNN.com:

February marks the beginning of Black History Month, a federally recognized, nationwide celebration that provides the opportunity for all Americans to reflect on the significant roles that African-Americans have played in the shaping of U.S. history. But how did this celebration come to be, and why does it take place in February?

We should emphasize not Negro History, but the Negro in history. What we need is not a history of selected races or nations, but the history of the world void of national bias, race hate, and religious prejudice.

– Dr. Carter G. Woodson (1875-1950) on founding Negro History Week, 1926

– Dr. Carter G. Woodson (1875-1950) on founding Negro History Week, 1926

Dr. Carter G. Woodson, considered a pioneer in the study of African-American history, is given much of the credit for Black History Month, and has been called the “Father of Black History.” The son of former slaves, Woodson spent his childhood working in coalmines and quarries. He received his education during the four-month term that was customary for black schools at the time. At 19, having taught himself English fundamentals and arithmetic, Woodson entered high school, where he completed a four-year curriculum in two years. He went on to receive his Master's degree in history from the University of Chicago, and he eventually earned a Ph.D from Harvard.

Disturbed that history textbooks largely ignored America's black population, Woodson took on the challenge of writing black Americans into the nation's history. To do this, Woodson established the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. He also founded the group's widely respected publication, the Journal of Negro History. In 1926, he developed Negro History Week. Woodson believed that “the achievements of the Negro properly set forth will crown him as a factor in early human progress and a maker of modern civilization.”

Woodson chose the second week of February for the celebration because it marks the birthdays of two men who greatly influenced the black American population: Frederick Douglass (February 14), an escaped slave who became one of the foremost black abolitionists and civil rights leaders in the nation, and President Abraham Lincoln (February 12), who signed the Emancipation Proclamation, which abolished slavery in America's confederate states. In 1976, Negro History Week expanded into Black History Month. The month is also sometimes referred to as African-American Heritage Month.

More here.

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard in The Daily Telegraph:

Professor Stiglitz, the former chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, told The Daily Telegraph that Britain should let the banks default on their vast foreign operations and start afresh with new set of healthy banks.

Professor Stiglitz, the former chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, told The Daily Telegraph that Britain should let the banks default on their vast foreign operations and start afresh with new set of healthy banks.

“The UK has been hit hard because the banks took on enormously large liabilities in foreign currencies. Should the British taxpayers have to lower their standard of living for 20 years to pay off mistakes that benefited a small elite?” he said.

“There is an argument for letting the banks go bust. It may cause turmoil but it will be a cheaper way to deal with this in the end. The British Parliament never offered a blanket guarantee for all liabilities and derivative positions of these banks,” he said.

More here.

By now, it's clear to everyone that we have inherited an economic crisis as deep and dire as any since the days of the Great Depression. Millions of jobs that Americans relied on just a year ago are gone; millions more of the nest eggs families worked so hard to build have vanished. People everywhere are worried about what tomorrow will bring.