Robert Crossley at the Hudson Review:

People are constantly telling Ophelia what to do. No sooner has Laertes left the room, with an injunction to remember his words to her, than Polonius, never one to mind his own business, asks Ophelia what her exchange with her brother was all about. The conversation between father and daughter that follows is squirm-worthy. The more Ophelia tries to explain how things stand between her and Hamlet—how he has behaved in courting her and how she has responded to the “many tenders / Of his affection to me”—the more her father belittles her. “You speak like a green girl”; “think yourself a baby”; “Tender yourself more dearly”; “Go to, go to.” Each time Ophelia tries to speak up for herself—and, for that matter, speak up for Hamlet—Polonius overrides her. Finally, in his last twenty lines, he stifles her effort at reasoning with him, adding a father’s authority to the brother’s condescension: “I would not, in plain terms, from this time forth / Have you so slander any moment leisure / As to give words or talk with the Lord Hamlet. / Look to’t, I charge you. Come your ways.” By the scene’s end any resistance left in Ophelia has wilted. Not for the last time she is silenced. “I shall obey, my lord.”

People are constantly telling Ophelia what to do. No sooner has Laertes left the room, with an injunction to remember his words to her, than Polonius, never one to mind his own business, asks Ophelia what her exchange with her brother was all about. The conversation between father and daughter that follows is squirm-worthy. The more Ophelia tries to explain how things stand between her and Hamlet—how he has behaved in courting her and how she has responded to the “many tenders / Of his affection to me”—the more her father belittles her. “You speak like a green girl”; “think yourself a baby”; “Tender yourself more dearly”; “Go to, go to.” Each time Ophelia tries to speak up for herself—and, for that matter, speak up for Hamlet—Polonius overrides her. Finally, in his last twenty lines, he stifles her effort at reasoning with him, adding a father’s authority to the brother’s condescension: “I would not, in plain terms, from this time forth / Have you so slander any moment leisure / As to give words or talk with the Lord Hamlet. / Look to’t, I charge you. Come your ways.” By the scene’s end any resistance left in Ophelia has wilted. Not for the last time she is silenced. “I shall obey, my lord.”

more here.

M

M AFTER THE NAKBA OF 1948

AFTER THE NAKBA OF 1948 Forced into exile in 1917 by the October Revolution, Nabokov had good reasons to champion freedom as passionately and consistently as he did. From his point of view and that of most Russian émigrés, the Bolsheviks substituted the tsarist tyranny with a tyranny of their own. For Nabokov in particular, this was especially painful because his father had been one of the “liberationists” who dedicated his life to transforming Russia into a modern liberal-democratic state. His father’s political activism and his murder in a bungled political assassination by far-right extremists is one of the most poignant chapters of Nabokov’s biography. Nabokov’s philosophically complex account of freedom is a consistent seam throughout his major works – and it has also led to confusion in their popular and critical reception.

Forced into exile in 1917 by the October Revolution, Nabokov had good reasons to champion freedom as passionately and consistently as he did. From his point of view and that of most Russian émigrés, the Bolsheviks substituted the tsarist tyranny with a tyranny of their own. For Nabokov in particular, this was especially painful because his father had been one of the “liberationists” who dedicated his life to transforming Russia into a modern liberal-democratic state. His father’s political activism and his murder in a bungled political assassination by far-right extremists is one of the most poignant chapters of Nabokov’s biography. Nabokov’s philosophically complex account of freedom is a consistent seam throughout his major works – and it has also led to confusion in their popular and critical reception. “The problem isn’t your memory, it’s that we have the wrong expectations for what memory is for in the first place,” Ranganath writes in his introduction, a theme that he returns to throughout the book. “

“The problem isn’t your memory, it’s that we have the wrong expectations for what memory is for in the first place,” Ranganath writes in his introduction, a theme that he returns to throughout the book. “ To understand Narendra Modi’s India, it is instructive to grasp the ideas of the Hindu Right’s greatest ideologue, the world of British colonial India in which they emerged, and the historical feebleness of the present regime.

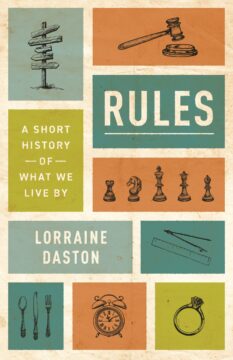

To understand Narendra Modi’s India, it is instructive to grasp the ideas of the Hindu Right’s greatest ideologue, the world of British colonial India in which they emerged, and the historical feebleness of the present regime. In the 1969 postscript to The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Thomas Kuhn distinguished two different senses in which ‘paradigm’, the technical term his book popularised, had been used. On the one hand, a paradigm denoted the ‘entire constellation of beliefs, values, techniques, and so on shared by the members of a given community’. In this first sense, paradigm was employed sociologically, an application Kuhn regretted in retrospect. ‘Disciplinary matrix’ became his preferred locution for the shared commitments defining a specific scientific community.

In the 1969 postscript to The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Thomas Kuhn distinguished two different senses in which ‘paradigm’, the technical term his book popularised, had been used. On the one hand, a paradigm denoted the ‘entire constellation of beliefs, values, techniques, and so on shared by the members of a given community’. In this first sense, paradigm was employed sociologically, an application Kuhn regretted in retrospect. ‘Disciplinary matrix’ became his preferred locution for the shared commitments defining a specific scientific community. O

O Who here comes from a savage race?” Professor James Shapiro shouted at his students.

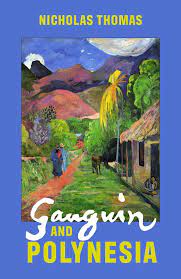

Who here comes from a savage race?” Professor James Shapiro shouted at his students. Today, says Thomas, ‘it feels difficult just to look at a Gauguin painting, without being told what to think’. The instructions tell us that he was ‘a sexual predator in life and a colonialist in his art’. Thomas’s aim is not to launder Gauguin’s reputation or undo recent decades of feminist art history and postcolonial studies but to eliminate some of the anachronism that inevitably arises when the past is examined, and judged, by contemporary mores.

Today, says Thomas, ‘it feels difficult just to look at a Gauguin painting, without being told what to think’. The instructions tell us that he was ‘a sexual predator in life and a colonialist in his art’. Thomas’s aim is not to launder Gauguin’s reputation or undo recent decades of feminist art history and postcolonial studies but to eliminate some of the anachronism that inevitably arises when the past is examined, and judged, by contemporary mores. “Western civilisation” would not exist without its Islamic, African, Indian and Chinese influences. To understand why, Quinn takes us back in time, beginning at the bustling port of Byblos in Lebanon in about 2000BC. It was the middle of the bronze age, which “inaugurated a new era of regular long-distance exchange”. Carbon dating techniques applied to recent archaeological findings provide compelling evidence about just how “globalized” the Mediterranean already was, 4,000 years ago. Welsh copper went to Scandinavia, and Cornish tin as far as Germany, for the forging of bronze weapons. Beads of Baltic amber, found in the graves of Mycenaean nobles, were made in Britain. A thousand years later, trade up and down the Atlantic seaboard meant that “Irish cauldrons became especially popular in northern Portugal”.

“Western civilisation” would not exist without its Islamic, African, Indian and Chinese influences. To understand why, Quinn takes us back in time, beginning at the bustling port of Byblos in Lebanon in about 2000BC. It was the middle of the bronze age, which “inaugurated a new era of regular long-distance exchange”. Carbon dating techniques applied to recent archaeological findings provide compelling evidence about just how “globalized” the Mediterranean already was, 4,000 years ago. Welsh copper went to Scandinavia, and Cornish tin as far as Germany, for the forging of bronze weapons. Beads of Baltic amber, found in the graves of Mycenaean nobles, were made in Britain. A thousand years later, trade up and down the Atlantic seaboard meant that “Irish cauldrons became especially popular in northern Portugal”.