From Wikipedia:

Racial segregation in the United States has meant the physical separation and provision of separate facilities (especially during the Jim Crow era), but it can also refer to other manifestations of racial discrimination such as separation of roles within an institution, such as the United States Armed Forces up to 1948 when black units were typically separated from white units but were led by white officers. Racial segregation in the United States can be divided into de jure and de facto segregation. De jure segregation, sanctioned or enforced by force of law, was stopped by federal enforcement of a series of Supreme Court decisions beginning with Brown vs. Board of Education in 1954. The process of throwing off legal segregation in the United States lasted through much of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s when civil rights demonstrations resulted in public opinion turning against enforced segregation. De facto segregation — segregation “in fact” — persists to varying degrees without sanction of law to the present day. The contemporary racial segregation seen in America in residential neighborhoods has been shaped by public policies, mortgage discrimination and redlining.

Racial segregation in the United States has meant the physical separation and provision of separate facilities (especially during the Jim Crow era), but it can also refer to other manifestations of racial discrimination such as separation of roles within an institution, such as the United States Armed Forces up to 1948 when black units were typically separated from white units but were led by white officers. Racial segregation in the United States can be divided into de jure and de facto segregation. De jure segregation, sanctioned or enforced by force of law, was stopped by federal enforcement of a series of Supreme Court decisions beginning with Brown vs. Board of Education in 1954. The process of throwing off legal segregation in the United States lasted through much of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s when civil rights demonstrations resulted in public opinion turning against enforced segregation. De facto segregation — segregation “in fact” — persists to varying degrees without sanction of law to the present day. The contemporary racial segregation seen in America in residential neighborhoods has been shaped by public policies, mortgage discrimination and redlining.

After Congress passed the Reconstruction Act of 1867, the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1870 providing the right to vote, and the Civil Rights Act of 1875 forbidding racial segregation in accommodations, Federal occupation troops in the South assured blacks the right to vote and to elect their own political leaders. The Reconstruction amendments asserted the supremacy of the national state and the formal equality under the law of everyone within it.[1] However this radical Reconstruction era would collapse because of multidimensional racialism related to the spread of democratic idealism. What began as region wide passage of ‘Jim Crow’ segregation laws that focused on issues of equal access to public activities and facilities would by 1910 have spread throughout the south, mandating the segregation of whites and blacks in the public sphere.

More here.

From The Guardian:

The complexity of Naomi Klein's portrayal of the rise of disaster capitalism, The Shock Doctrine, has won its author the inaugural £50,000 Warwick prize for writing. The biennial prize, run by Warwick University, is promising to be one of the most unusual prizes on the books calendar, not least because it will tackle a different theme every two years, with “complexity” chosen as its initial focus. Chair of judges and author of “weird fiction” China Miéville praised The Shock Doctrine as a “brilliant, provocative, outstandingly written investigation into some of the great outrages of our time” which has “started many debates, and will start many more”. The book charts Klein's four-year investigation into moments of collective crisis, such as 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina, dubbing the ways in which they are exploited by global corporations “disaster capitalism”.

The complexity of Naomi Klein's portrayal of the rise of disaster capitalism, The Shock Doctrine, has won its author the inaugural £50,000 Warwick prize for writing. The biennial prize, run by Warwick University, is promising to be one of the most unusual prizes on the books calendar, not least because it will tackle a different theme every two years, with “complexity” chosen as its initial focus. Chair of judges and author of “weird fiction” China Miéville praised The Shock Doctrine as a “brilliant, provocative, outstandingly written investigation into some of the great outrages of our time” which has “started many debates, and will start many more”. The book charts Klein's four-year investigation into moments of collective crisis, such as 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina, dubbing the ways in which they are exploited by global corporations “disaster capitalism”.

“At a time when the news out of the publishing industry is usually so bleak it's thrilling to be part of a bold new prize supporting writing, especially alongside such an exciting array of other books,” Klein said on learning of her win. She beat an extremely diverse shortlist which ranged from scientific theory to Spanish fiction to take the award, seeing off strong competition from Mad, Bad and Sad, Lisa Appignanesi's intricate study of the relationship between women and mental illness, and Alex Ross's Guardian first book award-winning history of 20th-century music, The Rest is Noise. Francisco Goldman's investigation into the murder of Guatemalan bishop Juan Gerardi, The Art of Political Murder, Stuart A Kauffman's Reinventing the Sacred and the solitary novel on the shortlist, Enrique Vila-Matas's study of an obsessive writer, Montano's Malady, completed the line-up.

More here.

Michael Agger in Slate:

Why is the Internet the place where civil discussion goes to die? It must be something in the tubes. Before there even was a mainstream Internet, in 1990, Electronic Frontier Foundation attorney Mike Godwin coined Godwin's Law: “As a Usenet discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches one.” If you put a group of slightly asocial, opinionated people behind usernames, the conversation descends into flame wars and miscellaneous insanity.

Why is the Internet the place where civil discussion goes to die? It must be something in the tubes. Before there even was a mainstream Internet, in 1990, Electronic Frontier Foundation attorney Mike Godwin coined Godwin's Law: “As a Usenet discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches one.” If you put a group of slightly asocial, opinionated people behind usernames, the conversation descends into flame wars and miscellaneous insanity.

Which is why I am so impressed with Ask MetaFilter, a question-and-answer site that grew out of the MetaFilter community in 2003. It's one of the few places on the Internet where you can find sensible, accommodating, actually helpful discussion. For example, last October, the user “Hands of Manos” posed the following query: “How can I be less cynical?” He went on to explain, “I hate most movies, I lost faith in the God I was raised to believe in as a child and I find very little joy in most things now a days” and noted, “My wife is pissed because I'm so negative and doubtful of everything.”

Thoughtful replies were posted immediately, with suggestions ranging from volunteering to banjo playing to avoiding “emotionally toxic” people to reading David McCullough's book on John Adams to looking at a blog that collects examples of how the world is getting better all the time.

More here.

Tuesday, February 24, 2009

Jason Wilson in The Smart Set:

Friends often accuse me of being too nostalgic. By afternoon, they say, I’ve become misty-eyed over what I’ve eaten for breakfast. That’s not completely true, I tell them. I’m sure there’s been a few bowls of cereal that have been unremembered or unremarked upon. But my protests are half-hearted, because I know my friends are right. Case in point: On a recent trip to Iceland, I became weepy at the sight of three sheep grazing in a grassy field underneath the summer midnight sun.

Friends often accuse me of being too nostalgic. By afternoon, they say, I’ve become misty-eyed over what I’ve eaten for breakfast. That’s not completely true, I tell them. I’m sure there’s been a few bowls of cereal that have been unremembered or unremarked upon. But my protests are half-hearted, because I know my friends are right. Case in point: On a recent trip to Iceland, I became weepy at the sight of three sheep grazing in a grassy field underneath the summer midnight sun.

Let me explain that this was my first trip to Iceland in several years. In my 20s, over the course of nine visits, I spent what some might consider to be an eccentric amount of time in Iceland. I would like to tell you that I had a grand purpose — that I was translating the ancient Sagas or convincing the Icelanders not to hunt whales. But no, when I was wasn’t driving aimlessly on gravel roads shooting photos of the most beautiful landscapes in the world, most of my time was spent hanging out in the bars and cafes of Reykjavík.

During one late summer visit, I fell in with a Finnish woman named Eeva-Liisa and a Danish woman named Trine, who were also artfully perfecting their aimlessness.

More

Fawcett, however, was convinced that the Amazon wilderness – an area virtually the size of the continental United States – concealed the remnants of at least one, and probably more, highly advanced civilizations. He was the last of a breed of explorers to venture into blank spots on the map with little more than a machete, a compass, and an almost divine sense of purpose, and he spent nearly two decades gathering evidence to prove his case and pinpointing a location. With his 21-year-old son, Jack, and Jack’s best friend, Raleigh Rimell, Fawcett finally set off into the Brazilian jungle to find the City of Z. Then he and his party vanished, giving rise to what has been described as “the greatest exploration mystery of the 20th century.” Fawcett had warned that no one should follow in his wake due to the danger, but scores of scientists, explorers, and adventurers plunged into the wilderness, determined to recover the Fawcett party, alive or dead, and to return with proof of Z. In February 1955, the New York Times claimed that Fawcett’s disappearance had set off more searches “than those launched through the centuries to find the fabulous El Dorado.” Some were wiped out by starvation and disease, or retreated in despair; others were murdered by tribesmen firing arrows dipped in poison. Then there were those adventurers who had gone to find Fawcett and, like him, simply disappeared in the forests that travelers had long ago christened the “green hell.”

more from Boston Globe Ideas here.

Cosma Shalizi over at Three-Toed Sloth:

Cosma Shalizi over at Three-Toed Sloth:

[T]here are many situations where Bayesian learning does seem to work reasonably effectively, which in light of the Freedman-Diaconis results needs explaining, ideally in a way which gives some guidance as to when we can expect it to work. This is the origin of the micro-field of Bayesian consistency or Bayesian nonparametrics, and it's here that I find I've written a paper, rather to my surprise.

I never intended to work on this. In the spring of 2003, I was going to the statistics seminar in Ann Arbor, and one week the speaker happened to be Yoav Freund, talking about this paper (I think) on model averaging for classifiers. I got hung up on why the weights of different models went down exponentially with the number of errors they'd made. It occurred to me that this was what would happen in a very large genetic algorithm, if a solution's fitness was inversely proportional to the number of errors it made, and there was no mutation or cross-over. The model-averaged prediction would just be voting over the population. This made me feel better about why model averaging was working, because using a genetic algorithm to evolve classifier rules was something I was already pretty familiar with.

The next day it struck me that this story would work just as well for Bayesian model averaging, with weights depending on the likelihood rather than the number of errors. In fact, I realized, Bayes's rule just is the discrete-time replicator equation, with different hypotheses being so many different replicators, and the fitness function being the conditional likelihood.

As you know, Bob, the replicator dynamic is a mathematical representation of the basic idea of natural selection. There are different kinds of things, the kinds being called “replicators”, because things of one kind cause more things of that same kind to come into being. The average number of descendants per individual is the replicator's fitness; this can depend not only on the properties of the replicator and on time and chance, but also on the distribution of replicators in the population; in that case the fitness is “frequency dependent”. In its basic form, fitness-proportional selection is the only evolutionary mechanism: no sampling, no mutation, no cross-over, and of course no sex. The result is that replicators with above-average fitness increase their share of the population, while replicators with below-average fitness dwindle.

This is a pretty natural way of modeling half of the mechanism Darwin and Wallace realized was behind evolution, the “selective retention” part — what it leaves out is “blind variation”.

Perry Anderson in the LRB:

Berlusconi, catapulted onto the political stage as Craxi fled into exile, thus embodies perhaps the deepest irony in the postwar history of any Western society. The First Republic collapsed amid public outrage at the exposure of stratospheric levels of political corruption, only to give birth to a Second Republic dominated by a yet more flamboyant monument of illegality and corruption, Craxi’s own misdeeds dwarfed by comparison. Nor was the new venality confined to the ruler and his entourage. Beneath them, corruption has continued to flourish undiminished. A few months after the centre-left governor of Campania, Antonio Bassolino – formerly of the PCI – was indicted for fraud and malversation, the governor of Abruzzo, Ottavio Del Turco, another stalwart of the centre-left – formerly of the PSI – was also arrested, after a private-health tycoon confessed to having paid him six million euros in cash as protection money. Berlusconi is the capstone of a system that extends well beyond him. But, as a political actor, credit for the inversion of what was imagined would be the curing of the ills of the First Republic by the Second belongs in the first place to him. Italy has no more native tradition than trasformismo – the transformation of a political force by osmosis into its opposite, as classically practised by Depretis in the late 19th century, absorbing the right into the official left, and Giolitti in the early 20th, co-opting labour reformism to the benefit of liberalism. The case of the Second Republic has been trasformismo on a grander scale: not a party, or a class, but an entire order converted into what it was intended to end.

Where the state has led, society has followed. The years since 1993 have, in one area of life after another, been the most calamitous since the fall of Fascism. Of late, they have produced probably the two most scalding inventories of avarice, injustice, dereliction and failure to appear in any European country since the war. The works of a pair of crusading journalists for Corriere della Sera, Gian Antonio Stella and Sergio Rizzo, La Casta and La Deriva, have both been bestsellers – the first ran through 23 editions in six months – and they deserve to be. What do they reveal? To begin with, the greed of the political class running the country.

Via DeLong, Felix Salmon in Wired:

Via DeLong, Felix Salmon in Wired:

When the price of a credit default swap goes up, that indicates that default risk has risen. Li's breakthrough was that instead of waiting to assemble enough historical data about actual defaults, which are rare in the real world, he used historical prices from the CDS market. It's hard to build a historical model to predict Alice's or Britney's behavior, but anybody could see whether the price of credit default swaps on Britney tended to move in the same direction as that on Alice. If it did, then there was a strong correlation between Alice's and Britney's default risks, as priced by the market. Li wrote a model that used price rather than real-world default data as a shortcut (making an implicit assumption that financial markets in general, and CDS markets in particular, can price default risk correctly).

It was a brilliant simplification of an intractable problem. And Li didn't just radically dumb down the difficulty of working out correlations; he decided not to even bother trying to map and calculate all the nearly infinite relationships between the various loans that made up a pool. What happens when the number of pool members increases or when you mix negative correlations with positive ones? Never mind all that, he said. The only thing that matters is the final correlation number—one clean, simple, all-sufficient figure that sums up everything.

The effect on the securitization market was electric. Armed with Li's formula, Wall Street's quants saw a new world of possibilities. And the first thing they did was start creating a huge number of brand-new triple-A securities. Using Li's copula approach meant that ratings agencies like Moody's—or anybody wanting to model the risk of a tranche—no longer needed to puzzle over the underlying securities. All they needed was that correlation number, and out would come a rating telling them how safe or risky the tranche was.

As a result, just about anything could be bundled and turned into a triple-A bond—corporate bonds, bank loans, mortgage-backed securities, whatever you liked. The consequent pools were often known as collateralized debt obligations, or CDOs. You could tranche that pool and create a triple-A security even if none of the components were themselves triple-A. You could even take lower-rated tranches of other CDOs, put them in a pool, and tranche them—an instrument known as a CDO-squared, which at that point was so far removed from any actual underlying bond or loan or mortgage that no one really had a clue what it included. But it didn't matter. All you needed was Li's copula function.

Claudia Roth Pierpont in the New Yorker:

Claudia Roth Pierpont in the New Yorker:

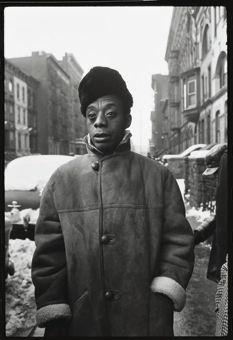

Baldwin had been fleeing from place to place for much of his adult life. He was barely out of his teens when he left his Harlem home for Greenwich Village, in the early forties, and he had escaped altogether at twenty-four, in 1948, buying a one-way ticket to Paris, with no intention of coming back. His father was dead by then, and his mother had eight younger children whom it tortured him to be deserting; he didn’t have the courage to tell her he was going until the afternoon he left. There was, of course, no shortage of reasons for a young black man to leave the country in 1948. Devastation was all around: his contemporaries, out on Lenox Avenue, were steadily going to jail or else were on “the needle.” His father, a factory worker and a preacher—“he was righteous in the pulpit,” Baldwin said, “and a monster in the house”—had died insane, poisoned with racial bitterness. Baldwin had also sought refuge in the church, becoming a boy preacher when he was fourteen, but had soon realized that he was hiding from everything he wanted and feared he could never achieve. He began his first novel, about himself and his father, around the time he left the church, at seventeen. Within a few years, he was publishing regularly in magazines; book reviews, mostly, but finally an essay and even a short story. Still, who really believed that he could make it as a writer? In America?

The answer to both questions came from Richard Wright. Although Baldwin seemed a natural heir to the Harlem Renaissance—he was born right there, in 1924, and Countee Cullen was one of his schoolteachers—the bittersweet poetry of writers like Cullen and Langston Hughes held no appeal for him. It was Wright’s unabating fury that hit him hard. Reading “Native Son,” Wright’s novel about a Negro rapist and murderer, Baldwin was stunned to recognize the world that he saw around him.

Reveille for Two Poets

George De Gregorio

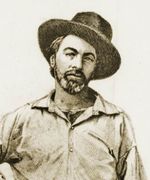

Wake up, Walt Whitman!

you’ve got a message:

America is still singing your songs,

you’re on the top 20 list

with the rappers and the throngs.

Lilacs still bloom in the dooryard in the spring

and the Song of Myself still holds.

Wake up William Carlos Williams!

a telegram for you sir.

Paterson is still alive and teeming

as Latinos and Blacks and others

yearn to breathe free.

Your Catholic bells are still ringing

and the Red Wheel Barrow

is still catching water.

Your little old sleepy hometown

is breaking out the glad-rags to celebrate you 125th

with a symposium of your songs — ad infinitum.

Don’t laugh Walt! Don’t laugh Carlos!

Your poetic clout still keeps America singing.

Together, you bridged three centuries

to this historic moment:

Obama, a black man,

and Hillary, a woman, together

are the first of their kind

to trade gibes in pursuit of a nomination

for President of the United States.

In the bank the other day

your songs were on full display.

The young teller was a beautiful Thai girl.

Her nameplate told it all:

she had become Mrs. Harrington, USA.

Get the pitch, Walt? What do you say Carlos?

America is still singing your triumphant songs.

Your songs of prophecy have lasted longer

than you had hoped.

Your songs have spawned an epidemic

which has infected 300 million;

there’s no telling what changes they will bring:

a calm or a whirlwind.

From Wikipedia:

The first recorded Africans in British North America (including most of the future United States) arrived in 1619 as indentured servants who settled in Jamestown, Virginia. As English settlers died from harsh conditions more and more Africans were brought to work as laborers. They for many years were similar in legal position to poor English indenturees, who traded several years labor in exchange for passage to America.[7] Africans could legally raise crops and cattle to purchase their freedom.[8] They raised families, marrying other Africans and sometimes intermarrying with Native Americans or English settlers.[9] By the 1640s and 1650s, several African families owned farms around Jamestown and some became wealthy by colonial standards. The popular conception of a race-based slave system did not fully develop until the 1700s. The first black congregations and churches were organized before 1800 in both northern and southern cities following the Great Awakening. During the 1770s Africans, both enslaved and free, helped rebellious English colonists secure American Independence by defeating the British in the American Revolution.[10] Africans and Englishmen fought side by side and were fully integrated.[11] James Armistead, an African American, played a large part in making possible the 1781 Yorktown victory that established the United States as an independent nation.[12] Other prominent African Americans were Prince Whipple and Oliver Cromwell, who are both depicted in the front of the boat in George Washington's famous 1776 Crossing the Delaware portrait.

The first recorded Africans in British North America (including most of the future United States) arrived in 1619 as indentured servants who settled in Jamestown, Virginia. As English settlers died from harsh conditions more and more Africans were brought to work as laborers. They for many years were similar in legal position to poor English indenturees, who traded several years labor in exchange for passage to America.[7] Africans could legally raise crops and cattle to purchase their freedom.[8] They raised families, marrying other Africans and sometimes intermarrying with Native Americans or English settlers.[9] By the 1640s and 1650s, several African families owned farms around Jamestown and some became wealthy by colonial standards. The popular conception of a race-based slave system did not fully develop until the 1700s. The first black congregations and churches were organized before 1800 in both northern and southern cities following the Great Awakening. During the 1770s Africans, both enslaved and free, helped rebellious English colonists secure American Independence by defeating the British in the American Revolution.[10] Africans and Englishmen fought side by side and were fully integrated.[11] James Armistead, an African American, played a large part in making possible the 1781 Yorktown victory that established the United States as an independent nation.[12] Other prominent African Americans were Prince Whipple and Oliver Cromwell, who are both depicted in the front of the boat in George Washington's famous 1776 Crossing the Delaware portrait.

Picture: An artist's conception of Crispus Attucks, the first “martyr” of the American Revolution.

More here.

John Tierny in The New York Times:

Why, since President Obama promised to “restore science to its rightful place” in Washington, do some things feel not quite right? First there was Steven Chu, the physicist and new energy secretary, warning The Los Angeles Times that climate change could make water so scarce by century’s end that “there’s no more agriculture in California” and no way to keep the state’s cities going, either. Then there was the hearing in the Senate to confirm another physicist, John Holdren, to be the president’s science adviser. Dr. Holdren was asked about some of his gloomy neo-Malthusian warnings in the past, like his calculation in the 1980s that famines due to climate change could leave a billion people dead by 2020. Did he still believe that?

Why, since President Obama promised to “restore science to its rightful place” in Washington, do some things feel not quite right? First there was Steven Chu, the physicist and new energy secretary, warning The Los Angeles Times that climate change could make water so scarce by century’s end that “there’s no more agriculture in California” and no way to keep the state’s cities going, either. Then there was the hearing in the Senate to confirm another physicist, John Holdren, to be the president’s science adviser. Dr. Holdren was asked about some of his gloomy neo-Malthusian warnings in the past, like his calculation in the 1980s that famines due to climate change could leave a billion people dead by 2020. Did he still believe that?

“I think it is unlikely to happen,” Dr. Holdren told the senators, but he insisted that it was still “a possibility” that “we should work energetically to avoid.” Well, I suppose it never hurts to go on the record in opposition to a billion imaginary deaths. But I have a more immediate concern: Will Mr. Obama’s scientific counselors give him realistic plans for dealing with global warming and other threats? To borrow a term from Roger Pielke Jr.: Can these scientists be honest brokers? Dr. Pielke, a professor in the environmental studies program at the University of Colorado, is the author of “The Honest Broker,” a book arguing that most scientists are fundamentally mistaken about their role in political debates. As a result, he says, they’re jeopardizing their credibility while impeding solutions to problems like global warming.

More here.

Monday, February 23, 2009

Images from the Civil Rights Movement.

Selma, Alabama.1964.

More here and here.

Sunday, February 22, 2009

In this powerful speech, the great author explains his controversial decision to accept a literary prize in Israel and why we need to fight the System.

Haruki Murakami in Salon:

I chose to come here rather than stay away. I chose to see for myself rather than not to see. I chose to speak to you rather than to say nothing.

I chose to come here rather than stay away. I chose to see for myself rather than not to see. I chose to speak to you rather than to say nothing.

Please do allow me to deliver one very personal message. It is something that I always keep in mind while I am writing fiction. I have never gone so far as to write it on a piece of paper and paste it to the wall: rather, it is carved into the wall of my mind, and it goes something like this:

“Between a high, solid wall and an egg that breaks against it, I will always stand on the side of the egg.”

Yes, no matter how right the wall may be and how wrong the egg, I will stand with the egg. Someone else will have to decide what is right and what is wrong; perhaps time or history will decide. If there were a novelist who, for whatever reason, wrote works standing with the wall, of what value would such works be?

More here.

#443: I tie my Hat— I crease my Shawl

Emily Dickinson

I tie my Hat—I crease my Shawl—

Life's little duties do—precisely—

As the very least

Were infinite—to me—

I put new Blossoms in the Glass—

And throw the old—away—

I push a petal from my Gown

That anchored there—I weigh

The time 'twill be till six o'clock

I have so much to do—

And yet—Existence—some way back—

Stopped—struck—my ticking—through—

We cannot put Ourself away

As a completed Man

Or Woman—When the Errand's done

We came to Flesh—upon—

There may be—Miles on Miles of Nought—

Of Action—sicker far—

To simulate—is stinging work—

To cover what we are

From Science—and from Surgery—

Too Telescopic Eyes

To bear on us unshaded—

For their—sake—not for Ours—

'Twould start them—

We—could tremble—

But since we got a Bomb—

And held it in our Bosom—

Nay—Hold it—it is calm—

Therefore—we do life's labor—

Though life's Reward—be done—

With scrupulous exactness—

To hold our Senses—on—

Jon Mooallem in the New York Times Magazine:

It was the first Friday in December, 23 degrees at dawn and nearly windless. Everyone was looking up.

It was the first Friday in December, 23 degrees at dawn and nearly windless. Everyone was looking up.

Operation Migration’s four ultralight planes floated into view over some oak and maple trees, then passed over the small, white chapel. An ultralight is powered by a massive rear propeller. In the sky, it looks like a scaled-down Formula 1 car dangling under the wing of a hang glider. Because the little planes taxi on three wheels, pilots call them trikes. At 200 feet, the first pilot, Chris Gullikson, was perfectly visible in his trike’s open cockpit. He was wearing his whooping-crane costume, a white hooded helmet and white gown that looked like a cross between a beekeeping suit and a Ku Klux Klan get-up. Gullikson and the other trike pilots were going to pick up the 14 juvenile whooping cranes that they were, little by little, leading south for the winter. Traditionally, and for many millenniums, cranes learned to migrate by following other cranes. But traditions have changed. Outside the church, a plucky, silver-haired woman named Liz Condie was explaining to the spectators why, exactly, her team has had to dress up and step in.

More here.

Christopher Hart in The Times:

For all the achievements of science during the 20th century, its great heroic age, there remains a surprising number of absolutely fundamental questions still to be answered. Questions as basic as What Is Life? and Why Do We Die?

For all the achievements of science during the 20th century, its great heroic age, there remains a surprising number of absolutely fundamental questions still to be answered. Questions as basic as What Is Life? and Why Do We Die?

In this fascinating, bang-up-to-date report from the outer limits of scientific knowledge today, New Scientist writer Michael Brooks examines 13 of the most urgent scientific mysteries in turn.

One of the great discoveries of 20th-century science was that our universe is expanding. The discovery, however, led straight to another puzzle. The puzzle is, there's nowhere near enough matter to prevent the expanding universe from blowing apart completely into a vast, sterile infinity of lifeless interstellar dust. So how come we live in a lumpy universe, one of the lumps being the planet on which we live? There must be more matter than we can see: the famous dark matter and, to go with it, something even more mysterious – dark energy.

To date, however, there's not a shred of evidence for either, even though teams of scientists have been looking for years.

More here.

From mije.org:

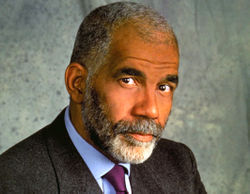

They could be called the integrationists, the young African American men and women who pushed open the doors of mainstream media and paved the way for journalists of color. Young journalists such as Nancy Maynard, Ed Bradley, Earl Caldwell, Charlayne Hunter Gault, Claude Lewis and Wallace Terry reported, organized, mentored and raised the bar for generations to come.

They could be called the integrationists, the young African American men and women who pushed open the doors of mainstream media and paved the way for journalists of color. Young journalists such as Nancy Maynard, Ed Bradley, Earl Caldwell, Charlayne Hunter Gault, Claude Lewis and Wallace Terry reported, organized, mentored and raised the bar for generations to come.

Ed Bradley

One could say that Ed Bradley in part owes his career to a popular Philadelphia radio DJ. Georgie Woods, after all, was the one who came to Bradley's college and gave a talk that inspired Bradley to become a DJ. Cheyney State was a teacher's college and Woods was there to talk to the senior class about using community resources to reach out to kids. Bradley, however, was more interested in Woods' work in the studio. Woods invited the young teacher to WDAS and as Bradley toured the station his life's mission became clearer.

“I just knew when I walked out there that night that I was put on this earth to be on radio,” he says.

Bradley spent everyday at the station, turning his attention to music, sports and some news. When he graduated from Cheyney and began teaching, he went to the station in the evenings. His friend and mentor Del Sheilds, the station's jazz DJ, always encouraged him to focus on news. That, Sheilds told him, was where the opportunities were.

More here.

Racial segregation in the United States has meant the physical separation and provision of separate facilities (especially during the Jim Crow era), but it can also refer to other manifestations of racial discrimination such as separation of roles within an institution, such as the United States Armed Forces up to 1948 when black units were typically separated from white units but were led by white officers. Racial segregation in the United States can be divided into de jure and de facto segregation. De jure segregation, sanctioned or enforced by force of law, was stopped by federal enforcement of a series of Supreme Court decisions beginning with Brown vs. Board of Education in 1954. The process of throwing off legal segregation in the United States lasted through much of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s when civil rights demonstrations resulted in public opinion turning against enforced segregation. De facto segregation — segregation “in fact” — persists to varying degrees without sanction of law to the present day. The contemporary racial segregation seen in America in residential neighborhoods has been shaped by public policies, mortgage discrimination and redlining.