Wait a Minute

I open my eyes in the Morning.

For a minute

I am neither here nor there.

Then in the next minute

I am here but starting

to be there.

The day has begun.

I will get up

and start to seek,

and continue starting,

so that every minute of this day

will begin with an anticipation

of the promise of the next one.

All day long and into the evening,

every minute of my waking hours,

I will not be here

because I am seeking

to be there.

I tell myself —

a pill will do it,

a walk in the fine fresh air will do it,

a Villa-Lobos prelude will do it,

a message on my answering machine will do it,

a good library book will do it,

a glass of wine at five o’clock will do it,

a good dinner will do it.

I close my eyes in the evening,

and say to myself,

with relief at the day’s ending:

a good night’s sleep will do it.

Every day is the same.

I never stop to ask:

“Do what?”

I never think to look for

what it is

that lies between the

beginning of the minute

and the end of it.

by Peggy Freydberg

from Poems from the Pond

Hybrid Nation, 2015

The contemporary world of botany that Schlanger explores in “The Light Eaters” is still divided over the matter of how plants sense the world and whether they can be said to communicate. But, in the past twenty years, the idea that plants communicate has gained broader acceptance. Research in recent decades has shown garden-variety lima beans protecting themselves by synthesizing and releasing chemicals to summon the predators of the insects that eat them; lab-grown pea shoots navigating mazes and responding to the sound of running water; and a chameleonic vine in the jungles of Chile mimicking the shape and color of nearby plants by a mechanism that’s not yet understood.

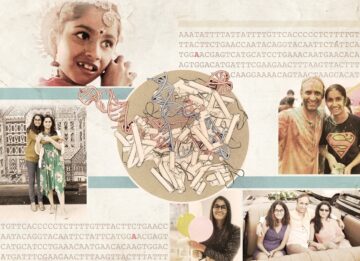

The contemporary world of botany that Schlanger explores in “The Light Eaters” is still divided over the matter of how plants sense the world and whether they can be said to communicate. But, in the past twenty years, the idea that plants communicate has gained broader acceptance. Research in recent decades has shown garden-variety lima beans protecting themselves by synthesizing and releasing chemicals to summon the predators of the insects that eat them; lab-grown pea shoots navigating mazes and responding to the sound of running water; and a chameleonic vine in the jungles of Chile mimicking the shape and color of nearby plants by a mechanism that’s not yet understood. When researcher Arkasubhra Ghosh finally met Uditi Saraf, he hoped that there was still a chance to save her. Ghosh and his collaborators were racing to design a one-off treatment that would edit the DNA in the 20-year-old woman’s brain cells and get them to stop producing toxic proteins. It was an approach that had never been tried before, with a long list of reasons for why it might not work. But the team was making swift progress. The researchers were maybe six months away from being ready to give Uditi the therapy, Ghosh told her parents over breakfast at their home outside New Delhi last June. Even so, Uditi’s mother was not satisfied. Work faster, she urged him.

When researcher Arkasubhra Ghosh finally met Uditi Saraf, he hoped that there was still a chance to save her. Ghosh and his collaborators were racing to design a one-off treatment that would edit the DNA in the 20-year-old woman’s brain cells and get them to stop producing toxic proteins. It was an approach that had never been tried before, with a long list of reasons for why it might not work. But the team was making swift progress. The researchers were maybe six months away from being ready to give Uditi the therapy, Ghosh told her parents over breakfast at their home outside New Delhi last June. Even so, Uditi’s mother was not satisfied. Work faster, she urged him. Pale Fire is one of the greatest books I’ve ever read. It is so great it is terrifying to write about. This is not something I would normally confess, but in this case it seems better to just come out and say it, lest the reader feel the awful stammering of suppressed terror quavering through my words without knowing what they are feeling. It is terrifying! But I want to do it anyway, because although mighty brains from all over the planet have weighed in on the subject with breath-taking and exhaustive scholarly ardour, I feel that something essential about the book remains not exactly unseen but distinctly understated.

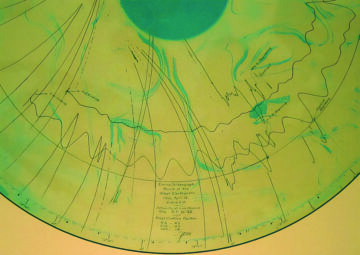

Pale Fire is one of the greatest books I’ve ever read. It is so great it is terrifying to write about. This is not something I would normally confess, but in this case it seems better to just come out and say it, lest the reader feel the awful stammering of suppressed terror quavering through my words without knowing what they are feeling. It is terrifying! But I want to do it anyway, because although mighty brains from all over the planet have weighed in on the subject with breath-taking and exhaustive scholarly ardour, I feel that something essential about the book remains not exactly unseen but distinctly understated. Earthquake professionals have made major strides in forecasting the long-term average rate of earthquakes in any given region. Unlike predictions, which involve meaningfully useful bounds in time, space, and magnitude, forecasts are made in terms of probabilities that an earthquake of a certain size will strike on decadal or longer timescales. For example, in 2008, seismologists predicted that there is an estimated 99.7% chance that at least one magnitude 6.7 or greater earthquake will occur in California over the next 30 years. Based on long-term odds, seismologists are known to tell the public that “it’s not a question of if, it’s a question of when” a damaging earthquake will strike.

Earthquake professionals have made major strides in forecasting the long-term average rate of earthquakes in any given region. Unlike predictions, which involve meaningfully useful bounds in time, space, and magnitude, forecasts are made in terms of probabilities that an earthquake of a certain size will strike on decadal or longer timescales. For example, in 2008, seismologists predicted that there is an estimated 99.7% chance that at least one magnitude 6.7 or greater earthquake will occur in California over the next 30 years. Based on long-term odds, seismologists are known to tell the public that “it’s not a question of if, it’s a question of when” a damaging earthquake will strike. Over the past decade, Ruth Ben-Ghiat has emerged as one of the English-speaking world’s leading experts on, and chroniclers of, authoritarian leaders in the twenty-first century. A professor of history and Italian studies at New York University and the author of

Over the past decade, Ruth Ben-Ghiat has emerged as one of the English-speaking world’s leading experts on, and chroniclers of, authoritarian leaders in the twenty-first century. A professor of history and Italian studies at New York University and the author of  Y

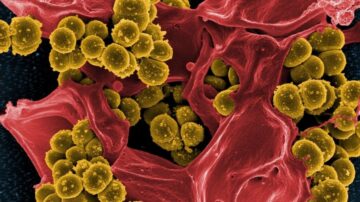

Y Humans and bacteria are in a perpetual war.

Humans and bacteria are in a perpetual war. M

M Dear Reader,

Dear Reader, George Salis: Your latest book is

George Salis: Your latest book is  A small, unassuming fern-like plant has something massive lurking within: the largest genome ever discovered, outstripping the

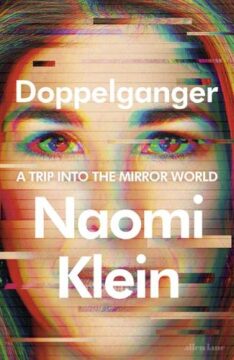

A small, unassuming fern-like plant has something massive lurking within: the largest genome ever discovered, outstripping the  It is a matter of being able to identify the true conspiracies, recognise genuine injustices and abuses of power, distinguish between credible and dubious information, plausible and implausible explanations. Klein makes a point of acknowledging that the irrational theories she examines in Doppelganger often arise from a justified sense that something is wrong – large pharmaceutical companies, for example, have real histories of unethical conduct and they really did make out like bandits during the pandemic. The question she confronts is how, and why, the valid instinct to distrust the powerful ends up being rerouted into bizarre fantasies.

It is a matter of being able to identify the true conspiracies, recognise genuine injustices and abuses of power, distinguish between credible and dubious information, plausible and implausible explanations. Klein makes a point of acknowledging that the irrational theories she examines in Doppelganger often arise from a justified sense that something is wrong – large pharmaceutical companies, for example, have real histories of unethical conduct and they really did make out like bandits during the pandemic. The question she confronts is how, and why, the valid instinct to distrust the powerful ends up being rerouted into bizarre fantasies. For the most part, Bowlero doesn’t build its own centers. Instead, it purchases existing ones and makes them over in the Bowlero style: dim lights, loud music, expensive cocktails. At Bowleros, bowling isn’t bowling. It’s “

For the most part, Bowlero doesn’t build its own centers. Instead, it purchases existing ones and makes them over in the Bowlero style: dim lights, loud music, expensive cocktails. At Bowleros, bowling isn’t bowling. It’s “