Tasneem Zehra Husain in New Humanist:

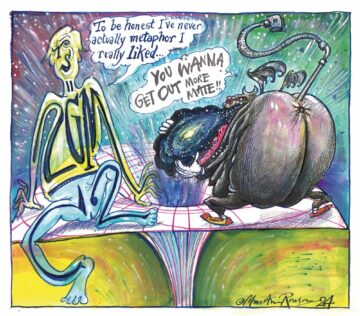

If science has a native tongue, it is mathematics. Equations capture, precisely, the relationships among the elements of a system; they allow us to pose questions and calculate answers. Numerically, these answers are precise and unambiguous – but what happens when we want to know what our calculations mean? Well, that is when we revert to our own native tongue: metaphor.

If science has a native tongue, it is mathematics. Equations capture, precisely, the relationships among the elements of a system; they allow us to pose questions and calculate answers. Numerically, these answers are precise and unambiguous – but what happens when we want to know what our calculations mean? Well, that is when we revert to our own native tongue: metaphor.

Why metaphor? Because that is how we think, how learn, how we parse the world. Metaphor comes from the Greek metaphora, a “transfer”; literally a “carrying over”. The very act of understanding (from the Old English: to stand in the midst of) implies the existence of a “between”, a bridge between new and known. In effect, a metaphor. How could it be otherwise? How else can we assimilate a new piece of knowledge, other than by linking it to something we already know? In doing so, we weave a web. When we wonder what something means, what we’re really asking is: what will it impact? If I pull on this thread here, where will my web tighten, where might it unravel?

When we can’t find a suitable metaphor to describe our scientific reality, we run into problems. Take, for instance, quantum mechanics. Most of the devices we use every day are built upon eerily accurate calculations made using quantum theory. Operationally, the theory is wildly successful, yet no one can make complete sense of it. Even scientists who wield the equations with ease don’t claim to truly understand quantum theory; we still don’t have a metaphor that works.

More here.

An orangutan in Sumatra surprised scientists when he was seen treating an open wound on his cheek with a poultice made from a medicinal plant. It’s the first scientific record of a wild animal healing a wound using a plant with known medicinal properties. The findings were published this week in Scientific Reports

An orangutan in Sumatra surprised scientists when he was seen treating an open wound on his cheek with a poultice made from a medicinal plant. It’s the first scientific record of a wild animal healing a wound using a plant with known medicinal properties. The findings were published this week in Scientific Reports O

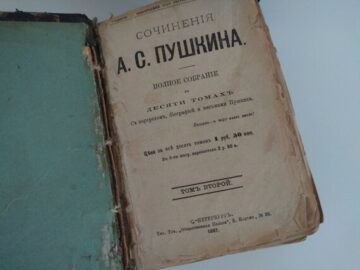

O In April 2022, soon after Russia invaded Ukraine, two men arrived at the library of the University of Tartu, Estonia’s second-largest city. They told the librarians they were Ukrainians fleeing war and asked to consult 19th-century first editions of works by Alexander Pushkin, Russia’s national poet, and Nikolai Gogol. Speaking Russian, they said they were an uncle and nephew researching censorship in czarist Russia so the nephew could apply for a scholarship to the United States. Eager to help, the librarians obliged. The men spent 10 days studying the books.

In April 2022, soon after Russia invaded Ukraine, two men arrived at the library of the University of Tartu, Estonia’s second-largest city. They told the librarians they were Ukrainians fleeing war and asked to consult 19th-century first editions of works by Alexander Pushkin, Russia’s national poet, and Nikolai Gogol. Speaking Russian, they said they were an uncle and nephew researching censorship in czarist Russia so the nephew could apply for a scholarship to the United States. Eager to help, the librarians obliged. The men spent 10 days studying the books. Former President Donald Trump testified in the New York civil fraud trial, earning rebukes from the judge for his off-topic comments. In the editorial cartoon gallery’s lead image, Nick Anderson pokes fun at Trump’s courtroom theatrics by showing him descending a golden escalator to the witness stand, a visual reference to the announcement at Trump Tower of his first presidential bid.

Former President Donald Trump testified in the New York civil fraud trial, earning rebukes from the judge for his off-topic comments. In the editorial cartoon gallery’s lead image, Nick Anderson pokes fun at Trump’s courtroom theatrics by showing him descending a golden escalator to the witness stand, a visual reference to the announcement at Trump Tower of his first presidential bid. Quick pop quiz: Prior to this week, what was Taylor Swift’s last new No. 1 hit on Billboard’s Hot 100?

Quick pop quiz: Prior to this week, what was Taylor Swift’s last new No. 1 hit on Billboard’s Hot 100? In China we have a saying that reading a banned book on a snowy night is one of the true joys of life. From this, one can well imagine the kind of satisfaction that reading a banned book may bring—like candy locked up in a cabinet, it releases a sweet fragrance into solitary spaces. Whenever I travel abroad, I am invariably introduced as China’s most controversial and most censored author. I neither agree nor disagree with this characterization—I’m not bothered by it, but neither do I feel particularly honored by it.

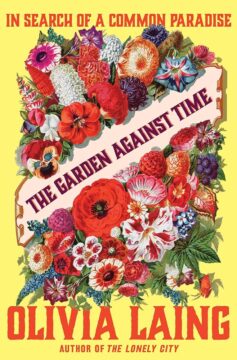

In China we have a saying that reading a banned book on a snowy night is one of the true joys of life. From this, one can well imagine the kind of satisfaction that reading a banned book may bring—like candy locked up in a cabinet, it releases a sweet fragrance into solitary spaces. Whenever I travel abroad, I am invariably introduced as China’s most controversial and most censored author. I neither agree nor disagree with this characterization—I’m not bothered by it, but neither do I feel particularly honored by it. The German forester Peter Wohlleben’s surprise bestseller, The Hidden Life of Trees (published in English in 2016), has inaugurated a new tree discourse, which sees them not as inert objects but

The German forester Peter Wohlleben’s surprise bestseller, The Hidden Life of Trees (published in English in 2016), has inaugurated a new tree discourse, which sees them not as inert objects but  Artificial intelligence is enabling India’s politicians to be everywhere at once in the world’s largest election by cloning their voices and digital likenesses. Even dead public figures, such as politician and actress Jayaram Jayalalithaa, are getting digitally resurrected to canvass support in what is shaping up to be the biggest test yet of democratic elections in the age of

Artificial intelligence is enabling India’s politicians to be everywhere at once in the world’s largest election by cloning their voices and digital likenesses. Even dead public figures, such as politician and actress Jayaram Jayalalithaa, are getting digitally resurrected to canvass support in what is shaping up to be the biggest test yet of democratic elections in the age of  O

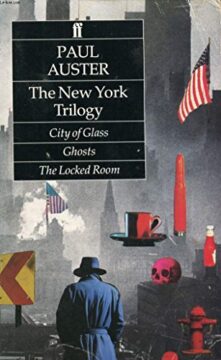

O “It was a wrong number that started it, the telephone ringing three times in the dead of night, and the voice on the other end asking for someone he was not.” So begins City of Glass, the first book in what became Paul Auster’s acclaimed New York Trilogy. Published in 1985, it marked the arrival of a truly unique voice in fiction, one quite distinct from many of the currents in American writing at the time. This was not the minimalism of Raymond Carver, or the expansiveness of Tom Wolfe; this was work much more connected to the traditions of European literature in which Auster was steeped. Paul Auster, who has died at the age of 77 in Brooklyn – where he lived his wife, the writer Siri Hustvedt – leaves a lasting and distinctive legacy in English-language literature.

“It was a wrong number that started it, the telephone ringing three times in the dead of night, and the voice on the other end asking for someone he was not.” So begins City of Glass, the first book in what became Paul Auster’s acclaimed New York Trilogy. Published in 1985, it marked the arrival of a truly unique voice in fiction, one quite distinct from many of the currents in American writing at the time. This was not the minimalism of Raymond Carver, or the expansiveness of Tom Wolfe; this was work much more connected to the traditions of European literature in which Auster was steeped. Paul Auster, who has died at the age of 77 in Brooklyn – where he lived his wife, the writer Siri Hustvedt – leaves a lasting and distinctive legacy in English-language literature.