Benjamin Balint at the NYT:

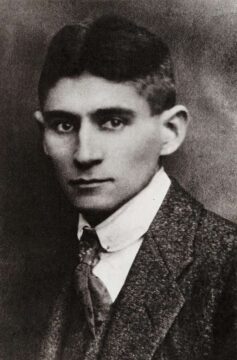

In his novella “The Prague Orgy,” Philip Roth has a Czech writer say: “When I studied Kafka, the fate of his books in the hands of the Kafkologists seemed to me to be more grotesque than the fate of Josef K.” Just as Franz Kafka’s prose both demands and evades interpretation, something about his legacy has both solicited and resisted claims of ownership.

In his novella “The Prague Orgy,” Philip Roth has a Czech writer say: “When I studied Kafka, the fate of his books in the hands of the Kafkologists seemed to me to be more grotesque than the fate of Josef K.” Just as Franz Kafka’s prose both demands and evades interpretation, something about his legacy has both solicited and resisted claims of ownership.

Despite his astonishing clairvoyance about the impersonal cruelty of the bureaucratic state and the profound alienation of contemporary life, Kafka could not have foreseen how many admirers would read and misread his enigmatic fictions after his death, nor how many would-be heirs would seek to appropriate him as their own in the century since. Competing claims began to swirl almost as soon as Kafka died of tuberculosis, 100 years ago this June, a month short of his 41st birthday. Max Brod — close friend, betrayer of Kafka’s last instruction to burn his manuscripts, heavy-handed editor of his diaries and unfinished novels, and author of the first Kafka biography — depicted him as a modern-day “saint” whose stories and parables “are among the most typically Jewish documents of our time.”

more here.

There’s been renewed debate around Bryan Caplan’s The Case Against Education recently, so I want to discuss one way I think about this question.

There’s been renewed debate around Bryan Caplan’s The Case Against Education recently, so I want to discuss one way I think about this question. I

I Jules Howard is no stranger to sex. A science writer and zoological correspondent, his gleefully amusing 2014 book

Jules Howard is no stranger to sex. A science writer and zoological correspondent, his gleefully amusing 2014 book  A

A The quantum revolution in physics played out over a period of

The quantum revolution in physics played out over a period of  In the early fifth century BC, the Olympic boxer Kleomedes was disqualified from a match after killing his opponent with a foul move. Outraged at being deprived of the victory and its attendant prize, he became “mad with grief” and tore down a school in his hometown, killing many of the children who were studying there. Kleomedes managed to escape the angry mob that soon pursued him, and disappeared without trace. When the community sought answers from the oracle at Delphi, they were told that Kleomedes was now a hero, and should be honored accordingly with sacrifices. This the people did, and continued to do for centuries to come.

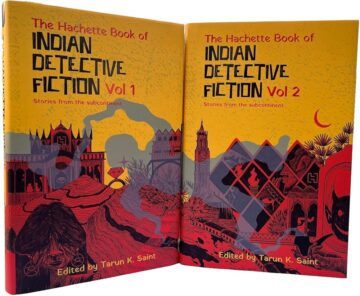

In the early fifth century BC, the Olympic boxer Kleomedes was disqualified from a match after killing his opponent with a foul move. Outraged at being deprived of the victory and its attendant prize, he became “mad with grief” and tore down a school in his hometown, killing many of the children who were studying there. Kleomedes managed to escape the angry mob that soon pursued him, and disappeared without trace. When the community sought answers from the oracle at Delphi, they were told that Kleomedes was now a hero, and should be honored accordingly with sacrifices. This the people did, and continued to do for centuries to come. Detective fiction in the West is often grouped with crime fiction and thrillers; but in detective fiction, the focus is on a puzzle and the process of solving it. It’s a game with the reader in which a mystery needs to be unraveled before the detective figures it out. In some places, the detective becomes a figure of interest in himself—detective figures have been, traditionally if less so at present, more often than not, men—a complex personality whose story is interesting and deserves an independent treatment of its own. It is a genre that solves problems, finds answers, holds the culprit accountable: all very attractive attributes for those who just like a good story.

Detective fiction in the West is often grouped with crime fiction and thrillers; but in detective fiction, the focus is on a puzzle and the process of solving it. It’s a game with the reader in which a mystery needs to be unraveled before the detective figures it out. In some places, the detective becomes a figure of interest in himself—detective figures have been, traditionally if less so at present, more often than not, men—a complex personality whose story is interesting and deserves an independent treatment of its own. It is a genre that solves problems, finds answers, holds the culprit accountable: all very attractive attributes for those who just like a good story. The latest wave of AI relies heavily on machine learning, in which software identifies patterns in data on its own, without being given any predetermined rules as to how to organize or classify the information. These patterns can be inscrutable to humans. The most advanced machine-learning systems use neural networks: software inspired by the architecture of the brain. They simulate layers of neurons, which transform information as it passes from layer to layer. As in human brains, these networks strengthen and weaken neural connections as they learn, but it’s hard to see why certain connections are affected. As a result, researchers often talk about AI as ‘

The latest wave of AI relies heavily on machine learning, in which software identifies patterns in data on its own, without being given any predetermined rules as to how to organize or classify the information. These patterns can be inscrutable to humans. The most advanced machine-learning systems use neural networks: software inspired by the architecture of the brain. They simulate layers of neurons, which transform information as it passes from layer to layer. As in human brains, these networks strengthen and weaken neural connections as they learn, but it’s hard to see why certain connections are affected. As a result, researchers often talk about AI as ‘ On September 17, 1978, U.S. President Jimmy Carter faced a momentous crisis. For nearly two weeks, he had been holed up at Camp David with Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, trying to hammer out a historic peace deal. Although the hard-liner Begin had proven intransigent on many issues, Carter had made enormous progress by going around him and negotiating directly with Israeli Foreign Minister Moshe Dayan, Defense Minister Ezer Weizman, and Legal Adviser Aharon Barak. On the 13th day, however, Begin drew the line. He announced he could compromise no further and was leaving. The talks on which Carter had staked his presidency would all be for naught.

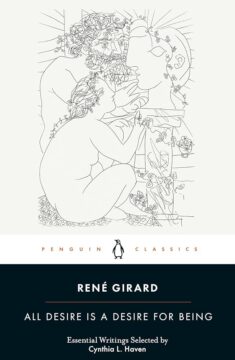

On September 17, 1978, U.S. President Jimmy Carter faced a momentous crisis. For nearly two weeks, he had been holed up at Camp David with Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, trying to hammer out a historic peace deal. Although the hard-liner Begin had proven intransigent on many issues, Carter had made enormous progress by going around him and negotiating directly with Israeli Foreign Minister Moshe Dayan, Defense Minister Ezer Weizman, and Legal Adviser Aharon Barak. On the 13th day, however, Begin drew the line. He announced he could compromise no further and was leaving. The talks on which Carter had staked his presidency would all be for naught. Girard’s corpus is not just an erudite self-help manual, however; his intellectual landscape is not intended to be therapeutic, and yet it is. What he came to see was not a comfort, however, but something fierce and intractable. What he learned about the individual also limns the destiny of our species. Our impossible plight: the mechanism of scapegoat violence—whether on the level of the individual, or society, or epoch—is rooted in the very imitation that teaches us to love and learn, in fact, the very tissue that connects us with the rest of humanity.

Girard’s corpus is not just an erudite self-help manual, however; his intellectual landscape is not intended to be therapeutic, and yet it is. What he came to see was not a comfort, however, but something fierce and intractable. What he learned about the individual also limns the destiny of our species. Our impossible plight: the mechanism of scapegoat violence—whether on the level of the individual, or society, or epoch—is rooted in the very imitation that teaches us to love and learn, in fact, the very tissue that connects us with the rest of humanity. Have you ever said “I hate you” to someone? What about using the “h-word” in casual conversation, like “I hate broccoli”? What are you really feeling when you say that you hate something or someone?

Have you ever said “I hate you” to someone? What about using the “h-word” in casual conversation, like “I hate broccoli”? What are you really feeling when you say that you hate something or someone? If you’ve ever vented to ChatGPT about troubles in life, the responses can sound empathetic. The chatbot delivers affirming support, and—when prompted—even gives advice like a best friend. Unlike older chatbots, the seemingly “empathic” nature of the latest AI models has already galvanized the psychotherapy community, with

If you’ve ever vented to ChatGPT about troubles in life, the responses can sound empathetic. The chatbot delivers affirming support, and—when prompted—even gives advice like a best friend. Unlike older chatbots, the seemingly “empathic” nature of the latest AI models has already galvanized the psychotherapy community, with