Jessie Kindig in The Point:

One June afternoon, I found myself idling about a meadow at the top of a forest in the northwest of the Pacific Northwest. I ate a rough lunch and slept, hands in pockets and cap on face. When I awoke, the sun was still high and the bees buzzed and the meadow kept its drowsiness on me—and so I opened a book of essays I’d been carrying around for the better part of a week and turned to Henry David Thoreau’s 1862 essay “Wild Apples,” one of his last, a praise song to extended metaphor.

One June afternoon, I found myself idling about a meadow at the top of a forest in the northwest of the Pacific Northwest. I ate a rough lunch and slept, hands in pockets and cap on face. When I awoke, the sun was still high and the bees buzzed and the meadow kept its drowsiness on me—and so I opened a book of essays I’d been carrying around for the better part of a week and turned to Henry David Thoreau’s 1862 essay “Wild Apples,” one of his last, a praise song to extended metaphor.

The essay opens plainly with exactly what it is, a conjecture that “the history of the apple–tree is connected with that of man.” Thoreau launches into a history of the apple, beginning with its classical lineage in Greece and Rome—fruit the gods competed to procure—and on through a discussion of the natural history of this most “humanized” of fruits. The cultivated apple, he says, emigrated with humans to the Americas—but the true wild apple is the indigenous crab, which Thoreau holds above all others. Wild apples, he says, are best taken with the “sauce” of the “November air”; indoors, they are too sour for words. The tang and smack of the wild apple is an acquired taste, not for farmers or townsfolk but meant for the special outsiders: errant boys, walkers like Thoreau, the Indian or “the wild-eyed woman of the fields.” Thoreau prefers an apple forest of cultivars gone to seed (as he so understands himself) growing alongside the indigenous crab apple: in this he finds a good American cider. But it certainly did not appear that things were headed that way in 1850, and so the essay is a lament. His notes on the truly wild apple are from memory rather than recent observation. Trees, by the mid-nineteenth century, are no longer free but are private property requiring purchasing, and so farmers are apt to claim the forest of the crab apple for farmland and grow cultivars in a “plat” by the house, where no saunterers, scalawags, witches or “Savages” may gain the gleanings. Says Thoreau: so goes the wild apple, so goes society.

More here.

In 19th century New York City, Theodore Gaillard Thomas enjoyed an unusual level of fame for a gynecologist. The reason, oddly enough, was milk. Between 1873 and 1880, the daring idea of transfusing milk into the body as a substitute for blood was being tested across the United States. Thomas was the most outspoken advocate of the practice.

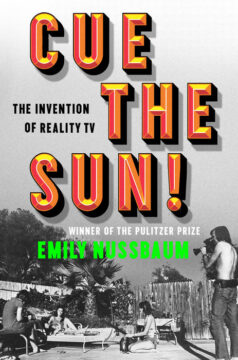

In 19th century New York City, Theodore Gaillard Thomas enjoyed an unusual level of fame for a gynecologist. The reason, oddly enough, was milk. Between 1873 and 1880, the daring idea of transfusing milk into the body as a substitute for blood was being tested across the United States. Thomas was the most outspoken advocate of the practice. EMILY NUSSBAUM, THE PULITZER-WINNING television critic and New Yorker staff writer, ends her well-researched, somewhat grueling book on the history of reality television, Cue the Sun!, with a reminder that critics have historically dismissed reality TV as a fad. Yet reality TV has not gone away. It’s more than just a fad, she writes, because “in the end, all our faces got stuck that way.”

EMILY NUSSBAUM, THE PULITZER-WINNING television critic and New Yorker staff writer, ends her well-researched, somewhat grueling book on the history of reality television, Cue the Sun!, with a reminder that critics have historically dismissed reality TV as a fad. Yet reality TV has not gone away. It’s more than just a fad, she writes, because “in the end, all our faces got stuck that way.” In early May, Google announced it would be adding artificial intelligence to its search engine. When the new feature rolled out,

In early May, Google announced it would be adding artificial intelligence to its search engine. When the new feature rolled out,  In early 1824, 30 members of Vienna’s music community sent a letter to Ludwig van Beethoven

In early 1824, 30 members of Vienna’s music community sent a letter to Ludwig van Beethoven  F

F WHEN HAMAS TERRORISTS

WHEN HAMAS TERRORISTS

S

S