Philip Ball in Aeon:

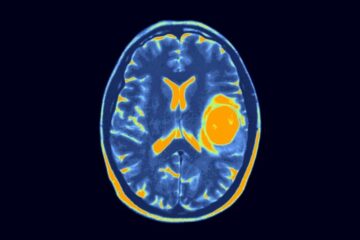

The genome sequence reveals the order in which the chemical building blocks (of which there are four distinct types) that make up our DNA are arranged along the molecule’s double-helical strands. Our genomes each have around 3 billion of these ‘letters’; reading them all is a tremendous challenge, but the Human Genome Project (HGP) transformed genome sequencing within the space of a couple of decades from a very slow and expensive procedure into something you can get done by mail order for the price of a meal for two. Since that first sequence was unveiled in 2000, hundreds of thousands of human genomes have now been decoded, giving an indication of the person-to-person variation in sequence. This information has provided a vital resource for biomedicine, enabling us, for example, to identify which parts of the genome correlate with which diseases and traits. And all that investment in gene-sequencing technology was more than justified merely by its use for studying and tracking the SARS-CoV-2 virus during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The genome sequence reveals the order in which the chemical building blocks (of which there are four distinct types) that make up our DNA are arranged along the molecule’s double-helical strands. Our genomes each have around 3 billion of these ‘letters’; reading them all is a tremendous challenge, but the Human Genome Project (HGP) transformed genome sequencing within the space of a couple of decades from a very slow and expensive procedure into something you can get done by mail order for the price of a meal for two. Since that first sequence was unveiled in 2000, hundreds of thousands of human genomes have now been decoded, giving an indication of the person-to-person variation in sequence. This information has provided a vital resource for biomedicine, enabling us, for example, to identify which parts of the genome correlate with which diseases and traits. And all that investment in gene-sequencing technology was more than justified merely by its use for studying and tracking the SARS-CoV-2 virus during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Nonetheless, as with the Apollo Moon landings – with which the HGP has been routinely compared – the decades that followed the initial triumph have seemed something of an anticlimax. For all its practical value, sequencing in itself offers little advance in understanding how the genome – or life itself – works.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

“This virus in its current state does not look like it has the characteristics of causing a pandemic. But with influenza viruses, that equation could entirely change with a single mutation,” says Scott Hensley, an immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

“This virus in its current state does not look like it has the characteristics of causing a pandemic. But with influenza viruses, that equation could entirely change with a single mutation,” says Scott Hensley, an immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Most economic debates are about income, not wealth. When we talk about income taxes, or welfare benefits, or labor’s share of national income, we’re talking about the amount of goods and services that get created every year, and how those goods and services get allocated among the various people in a society. But in the 2010s, we saw a lot of debate about wealth instead — wealth taxes, wealth inequality, and so on.

Most economic debates are about income, not wealth. When we talk about income taxes, or welfare benefits, or labor’s share of national income, we’re talking about the amount of goods and services that get created every year, and how those goods and services get allocated among the various people in a society. But in the 2010s, we saw a lot of debate about wealth instead — wealth taxes, wealth inequality, and so on. KARL KRAUS WROTE THAT EVERYTHING FITS WITH EVERYTHING ELSE. Maybe. Maybe everything in an artist’s corpus, no matter how incongruous, reflects, repeats, rhymes. Yet this is not the case for Percival Everett. No thematic or formal schema is suitable. He climbs the stairs sideways. His patently ridiculous conceits seem like challenges to his own mischievousness, bids to marry his uniquely sweeping curiosities to a bardic impulse. Charmingly, he’d never admit as much. “I know nothing,” he said in a recent New Yorker profile. “I’m just a dumb old cowboy.” Sure. It remains a considerable feat for Everett to have remained eccentric in the increasingly rational and prefabricated business of literature. He has his prevailing modes—racial satires, Westerns, crime procedurals, retellings of ancient myths, despondent autobiographical metafiction—but all of them are in flux, appearing in different admixtures. It’s hard to imagine another author pulling off, or even attempting, Glyph (1999),a novel about a toddler with a farcically high IQ; in Everett’s hands, the gambit is hilarious, bone-dry, and tragic. Erasure (2001), a canny parody of writers and racial fetishization, is even more affecting as a portrait of senescence. I Am Not Sidney Poitier (2009), a hysterical abuse of Ted Turner, the media, and various social structures, is also a repudiation of Everett’s previous work. (About Erasure, the author-character, Percival Everett, remarks, “I didn’t like writing it, and I didn’t like it when I was done with it.”) To apply superficial categories is to miss the point; Everett understands that each person is witness to a series of absurd debacles, and his fiction poses the question: What, if anything, is there to be made of our continued looking?

KARL KRAUS WROTE THAT EVERYTHING FITS WITH EVERYTHING ELSE. Maybe. Maybe everything in an artist’s corpus, no matter how incongruous, reflects, repeats, rhymes. Yet this is not the case for Percival Everett. No thematic or formal schema is suitable. He climbs the stairs sideways. His patently ridiculous conceits seem like challenges to his own mischievousness, bids to marry his uniquely sweeping curiosities to a bardic impulse. Charmingly, he’d never admit as much. “I know nothing,” he said in a recent New Yorker profile. “I’m just a dumb old cowboy.” Sure. It remains a considerable feat for Everett to have remained eccentric in the increasingly rational and prefabricated business of literature. He has his prevailing modes—racial satires, Westerns, crime procedurals, retellings of ancient myths, despondent autobiographical metafiction—but all of them are in flux, appearing in different admixtures. It’s hard to imagine another author pulling off, or even attempting, Glyph (1999),a novel about a toddler with a farcically high IQ; in Everett’s hands, the gambit is hilarious, bone-dry, and tragic. Erasure (2001), a canny parody of writers and racial fetishization, is even more affecting as a portrait of senescence. I Am Not Sidney Poitier (2009), a hysterical abuse of Ted Turner, the media, and various social structures, is also a repudiation of Everett’s previous work. (About Erasure, the author-character, Percival Everett, remarks, “I didn’t like writing it, and I didn’t like it when I was done with it.”) To apply superficial categories is to miss the point; Everett understands that each person is witness to a series of absurd debacles, and his fiction poses the question: What, if anything, is there to be made of our continued looking? O

O Getting too little sleep later in life is associated with an increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease. But paradoxically, so is getting too much sleep. While scientists are confident that a connection between sleep and dementia exists, the nature of that connection is complicated. It could be that poor sleep triggers changes in the brain that cause dementia. Or people’s sleep might be disrupted because of an underlying health issue that also affects brain health. And changes in sleep patterns can be an early sign of dementia itself. Here’s how experts think about these various connections and how to gauge your risk based on your own sleep habits.

Getting too little sleep later in life is associated with an increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease. But paradoxically, so is getting too much sleep. While scientists are confident that a connection between sleep and dementia exists, the nature of that connection is complicated. It could be that poor sleep triggers changes in the brain that cause dementia. Or people’s sleep might be disrupted because of an underlying health issue that also affects brain health. And changes in sleep patterns can be an early sign of dementia itself. Here’s how experts think about these various connections and how to gauge your risk based on your own sleep habits. O

O This is the third of a trio of reviews in which I take a brief detour into ants and collective behaviour more generally. I previously reviewed

This is the third of a trio of reviews in which I take a brief detour into ants and collective behaviour more generally. I previously reviewed  I

I Ashura is marked on the 10th day of Muharram, the first month of the Islamic calendar, by all Muslims. It marks the day Nuh (Noah) left the Ark and the day Musa (Moses) was saved from the Pharaoh of Egypt by God. The Prophet Muhammad used to fast on Ashura in Mecca, where it became a common tradition for the early Muslims. Ashura this year will be marked in most places on August 29. But for the Shia, it is also a major religious event to commemorate the martyrdom of Husayn Ibn Ali al-Hussein, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad, who died at the Battle of Karbala in 680 AD.

Ashura is marked on the 10th day of Muharram, the first month of the Islamic calendar, by all Muslims. It marks the day Nuh (Noah) left the Ark and the day Musa (Moses) was saved from the Pharaoh of Egypt by God. The Prophet Muhammad used to fast on Ashura in Mecca, where it became a common tradition for the early Muslims. Ashura this year will be marked in most places on August 29. But for the Shia, it is also a major religious event to commemorate the martyrdom of Husayn Ibn Ali al-Hussein, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad, who died at the Battle of Karbala in 680 AD. Every two weeks at Seattle Children’s Hospital in Washington, a five-year-old child stops by for a fresh dose of genetically engineered immune cells administered directly into the fluid around their brain.

Every two weeks at Seattle Children’s Hospital in Washington, a five-year-old child stops by for a fresh dose of genetically engineered immune cells administered directly into the fluid around their brain. Robinson opens

Robinson opens