by David Petrasek

The news is alarming: whole families killed in the mountain villages near Lebanon and massacres in Damascus; sectarian clashes between Christian, Alawite and Sunni communities risk a descent into full-scale civil war. The French are demanding intervention, and together with the British

threatening to dispatch warships to the Syrian coast; they seek an international mandate to do so. The Russians, wary of western plans in a region where their own influence is waning, are loath to agree.  The Turks are anxious about the escalating violence, but ill-equipped to respond on their own.

The Turks are anxious about the escalating violence, but ill-equipped to respond on their own.

Syria, in the summer of 2012? No, the Ottoman Syrian provinces – in 1860!

Thousands were killed in the clashes in 1860, and European newspapers printed lurid articles describing the violence against Christians. British and French objectives in the region were above all to extend their influence, lest the Russians fill the vacuum created by weakening Ottoman rule. The eventual French intervention, however, of several thousand troops, backed by the European powers, was justified in humanitarian terms – to protect innocent Christian lives. The French action is often referred to as the first modern example of a ‘humanitarian’ intervention.

There are, of course, important differences between the events of 1860 and a possible intervention to address the violence in Syria today. Recalling these events, however, reminds us that urge to intervene forcefully to protect innocents abroad is hardly new. Much is made of 24/7 news cycles, and the wonders of the Internet. But already in 1860, the public in Europe could be moved to outrage by newspaper accounts of atrocities in foreign lands.

If the impulse to intervene to protect innocents is not new, neither is the penchant to do so by invoking international law or moral arguments that appeal to the preservation of life or freedom. Just war theory is well-grounded in the law of nations. And armed interventions to seize colonies, or, more recently, to counter (or support) communist, nationalist or anti-colonial insurgency, have often invoked as rationales in their favour the overthrow of tyranny and despotism and putting and end to the suffering of innocents.

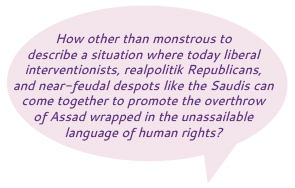

So what’s different about the debate today over a possible intervention in Syria, or indeed about NATO’s actual intervention in Libya in 2011? To some critics, not much; it’s just old wine in new bottles. They believe powerful states have invested the old interventionism with a new respectability, under the guise of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P). This doctrine, grounded in universal human rights, holds that when states are unable or unwilling to prevent mass atrocity within their borders, the UN has a duty to step in — including as a last resort by authorising the intervention of foreign troops.[1]To its most strident critics, R2P undermines the independence of states and is a cover for NATO (or western) interventionism.

Read more »

LONDON — To stroll out of Carlton Gardens into the elegant confines of the Royal Society is to find a trove of centuries-old wonders, from Sir Isaac Newton’s reflecting telescope to the first electric machine to fantastical illustrated catalogs of fish and birds. Then you enter the sunlight-suffused office of the society’s president, Sir Paul Nurse. With his spiky mass of white hair, broad nose, ready smile and thick work boots, he looks the part of old-fashioned knight of science ready to tramp through the fens. But this Nobel Prize winner in medicine offers a very 21st-century lament. “Policy debate these days involves trying to rubbish the science, and that is dangerous,” Dr. Nurse says. “Global warming denialists, those who oppose genetically modified crops and vaccinations, or the teaching of evolution: their trick is treat scientific argument as if it’s a political argument, and cherry-pick data.”