Steven E. Alford in Polaris:

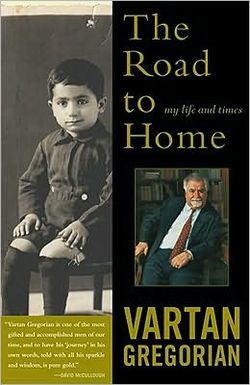

In an era in which dark-skinned foreigners fly airplanes into buildings, it’s helpful to remind ourselves that other dark-skinned foreigners have helped immeasurably in shaping this country for the better. Exhibit A is Vartan Gregorian, born an Armenian, raised a Christian, and who, to our eternal good fortune, chose America as his home. The Road to Home is the autobiography of a man who, as an impoverished child, was embarrassed to be seen walking to school in his disintegrating shoes; a man who, as an adult, became president of the New York Library, president of Brown University, and current president of the Carnegie Corporation. Born in 1934 in Tabriz, Iran, Gregorian was raised by his superstitious grandmother in Dickensian poverty. Happily, his intellectual gifts were recognized in his early teens, resulting in a scholarship to the Collège Arménian in Beruit. Regrettably, his relatives and benefactors had neglected to provide him with any money. Rescued by sympathetic locals, he was provided with meals at a local restaurant. However, his bequest did not cover the weekends, two nightmarish days in which he played psychological games with himself to take his mind off his hunger. Working diligently to learn French and Arabic (to add to his Armenian, Turkish, and Persian), Gregorian became one of the school’s top pupils and the protégé of its president, Simon Vratzian, “the last prime minister of the short-lived independent Republic of Armenia.” Following graduation, Gregorian was accepted at Stanford University (one of three Armenian students on campus) where, as a graduate student, he completed a groundbreaking historical study of modern Afghanistan. Much to the surprise of both the Armenian community and his future in-laws, the diminutive Gregorian proposed to tall, blonde Clare Russell on May 28,1959, which, he ironically notes, was Armenian Independence Day. Married in New Jersey the following year, their union produced three sons and a marriage that has lasted over forty years. Teaching in California, Gregorian was awarded the Danforth Foundations E. H. Harbison Award for Distinguished Teaching. John Silber enticed him to move to Austin to teach in the University of Texas’ honors program, Plan II, as well as become its principal administrator. Gregorian found Silber, a life-long friend, “ambitious, determined, and impatient, with a dose of misplaced temper.” One admires Gregorian’s capacity for understatement. Energetic, erudite, and funny, Gregorian’s aggressive teaching style embodied his approach toward his students’ education: “my ambition was to teach them to know the facts; to understand the nature and the impact of historical data and the role of individuals and ideas in shaping historical trends and social forces; to understand all the orthodoxies and be able to challenge them; to navigate through many cultures; to go beyond identity politics; and to learn how to reconcile the unique and the universal. In short, I wanted them to be able to think.” He notes that these ideas were impressed upon him by his teachers at Stanford, who “were an unusual group of people, from a different era, when students and teaching were the central preoccupation of the professors and the university, when the central mission of the university was education, when undergraduate education was the core of the university and the quality of graduate education the ultimate goal.”

In an era in which dark-skinned foreigners fly airplanes into buildings, it’s helpful to remind ourselves that other dark-skinned foreigners have helped immeasurably in shaping this country for the better. Exhibit A is Vartan Gregorian, born an Armenian, raised a Christian, and who, to our eternal good fortune, chose America as his home. The Road to Home is the autobiography of a man who, as an impoverished child, was embarrassed to be seen walking to school in his disintegrating shoes; a man who, as an adult, became president of the New York Library, president of Brown University, and current president of the Carnegie Corporation. Born in 1934 in Tabriz, Iran, Gregorian was raised by his superstitious grandmother in Dickensian poverty. Happily, his intellectual gifts were recognized in his early teens, resulting in a scholarship to the Collège Arménian in Beruit. Regrettably, his relatives and benefactors had neglected to provide him with any money. Rescued by sympathetic locals, he was provided with meals at a local restaurant. However, his bequest did not cover the weekends, two nightmarish days in which he played psychological games with himself to take his mind off his hunger. Working diligently to learn French and Arabic (to add to his Armenian, Turkish, and Persian), Gregorian became one of the school’s top pupils and the protégé of its president, Simon Vratzian, “the last prime minister of the short-lived independent Republic of Armenia.” Following graduation, Gregorian was accepted at Stanford University (one of three Armenian students on campus) where, as a graduate student, he completed a groundbreaking historical study of modern Afghanistan. Much to the surprise of both the Armenian community and his future in-laws, the diminutive Gregorian proposed to tall, blonde Clare Russell on May 28,1959, which, he ironically notes, was Armenian Independence Day. Married in New Jersey the following year, their union produced three sons and a marriage that has lasted over forty years. Teaching in California, Gregorian was awarded the Danforth Foundations E. H. Harbison Award for Distinguished Teaching. John Silber enticed him to move to Austin to teach in the University of Texas’ honors program, Plan II, as well as become its principal administrator. Gregorian found Silber, a life-long friend, “ambitious, determined, and impatient, with a dose of misplaced temper.” One admires Gregorian’s capacity for understatement. Energetic, erudite, and funny, Gregorian’s aggressive teaching style embodied his approach toward his students’ education: “my ambition was to teach them to know the facts; to understand the nature and the impact of historical data and the role of individuals and ideas in shaping historical trends and social forces; to understand all the orthodoxies and be able to challenge them; to navigate through many cultures; to go beyond identity politics; and to learn how to reconcile the unique and the universal. In short, I wanted them to be able to think.” He notes that these ideas were impressed upon him by his teachers at Stanford, who “were an unusual group of people, from a different era, when students and teaching were the central preoccupation of the professors and the university, when the central mission of the university was education, when undergraduate education was the core of the university and the quality of graduate education the ultimate goal.”

Gregorian’s dynamism, charisma, and intellectual gifts were such that by 1974 he became provost of the University of Pennsylvania. Passed over for the presidency owing to politics among the trustees, he accepted the presidency of the New York Public Library, placing him in New York’s social stratosphere, with Brook Astor as his patron. At a dinner welcoming him to New York, he found himself surrounded by people he had admittedly seen only on television. “I sat at Mrs. Astor’s right, I looked at all the dignitaries and glamorous people, the elegant apartment, and reflected on the distance between 1699 Church Street Tabriz, Iran, and 778 Park Avenue, New York.”

More here. (Note: Dear friend Vartan just gave me this amzing autobiography. Recommend highly!)

Peter Pomerantsev at Eurozine: