Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Sunday Poem

Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

,,

And miles to go before I sleep.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Park Chan-wook and the Funny Thing About Stomach-Churning Horror

Robert Ito in The New York Times:

Park Chan-wook is one of Asia’s most famous directors, an auteur beloved as much for his complex, often critical visions of his home country of South Korea as for scenes of stomach-churning horror. But when Park started work on “No Other Choice,” he really wanted to direct it as an American film, so much so that he spent 12 frustrating years trying to get financing from Hollywood studios. The source material, Donald E. Westlake’s 1997 horror thriller novel, “The Ax,” was based in the United States, “so it just felt very natural to me,” he said. “I didn’t put too much other thought in it.”

Park Chan-wook is one of Asia’s most famous directors, an auteur beloved as much for his complex, often critical visions of his home country of South Korea as for scenes of stomach-churning horror. But when Park started work on “No Other Choice,” he really wanted to direct it as an American film, so much so that he spent 12 frustrating years trying to get financing from Hollywood studios. The source material, Donald E. Westlake’s 1997 horror thriller novel, “The Ax,” was based in the United States, “so it just felt very natural to me,” he said. “I didn’t put too much other thought in it.”

Beyond the novel’s suburban East Coast setting, the plot and lead character also felt particularly American to the Korean director: a manager of a paper company has his life upended by corporate downsizing, and to secure a new job, he sets about murdering his rivals in increasingly gruesome ways. “This is a story about the capitalist system,” Park said. “I thought it would be best told in America, since America is the heart of capitalism.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

To see America’s greatest living painter, you’ll have to cross the pond

Sebastian Smee in The Washington Post:

“I’ve always wanted to be a history painter on a grand scale like Giotto and Géricault,” he said in 1994. As soon as you get interested in the “how” of things, you become conscious that they might have been done differently. That consciousness may open a crack of potential: They might yet be done differently.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Saturday, December 27, 2025

Transformation without Taxation

César Morales Oyarvide in Phenomenal World:

In his famous 1918 essay “The Crisis of the Tax State,” Joseph Schumpeter captured the essence of fiscal sociology, arguing that “The spirit of a people, its cultural level, its social structure, the deeds its policy may prepare—all this and more is written in its fiscal history … He who knows how to listen to its message here discerns the thunder of world history more clearly than anywhere else.” In Mexico, however, this principle seems to have been suspended. There the Schumpeterian thunder is not heard. The project of the Fourth Transformation (4T), launched by Andrés Manuel López Obrador in 2018 and passed down to Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo last year, has sought to reorganize domestic political power, and it has had considerable success—redefining the national narrative and restructuring public spending priorities. Yet it has not significantly altered the tax structure built by previous governments.

This fiscal silence is even more surprising in light of the experiences of other leftist administrations in Latin America. In Bolivia, Evo Morales combined strategic nationalizations with an aggressive expansion of the fiscal apparatus. In Brazil, successive PT governments broadened the tax base while transferring income to the poorest citizens. Despite grappling with high levels of informality and low trust in state institutions, these projects understood that without new resources, it would be impossible to create new social rights. The 4T, by contrast, has tried to square the circle of distribution without serious tax reform.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Pattiverse

James Wolcott in Sidecar:

2025 marks the fiftieth anniversary of Patti Smith’s debut album Horses, with Robert Mapplethorpe’s black and white cover portrait of the artist posed with her jacket slung over her shoulder, Frank Sinatra-style – ‘the most electrifying image I had ever seen of a woman of my generation’, exclaimed Camille Paglia, who reckoned it one of the most powerful portraits since the French Revolution. The record inside the cover sleeve hasn’t wilted either, retaining its classic status as a declaration of desperado intent, from the boppy ‘Redondo Beach’ to the trippy ‘Birdland’ to the unfolding vistas of ‘Gloria’ and ‘Land (of a Thousand Dances)’, where Patti could truly stretch out her skinny arms and fan out her fingers to spread the word. (As the choreographer Paul Taylor once quipped, that’s the definition of lyricism: long arms.) To celebrate the album’s fiftieth, Patti and her band have been touring triumphal live concert versions of Horses across the US and Europe, the rapturous reception at the London Palladium somewhat mottled when Patti brought out Johnny Depp for the encore anthem ‘People Have the Power’, Depp draped and layered in hipster duds in his continuing role as America’s premier hobosexual. Irate fans and commentators on both sides of the Atlantic squawked betrayal, trying to reconcile the populist idealism of Patti’s music and persona with jamming on stage with an alleged spouse abuser and celebrity prima donna who owns a private island in the Exumas.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Makers of Modern China

Zheng Xiaoqiong in Equator:

Introduction by Kaiser Kuo

I first encountered Zheng Xiaoqiong’s writing in a collection of Chinese worker poetry skillfully translated by Eleanor Goodman (2016). What struck me then about her poetry, and what remains true in this prose selection, is Zheng’s attentiveness to the texture of migrant-worker life. She restores dignity not through political theatrics, but through rigorous sensory detail: the clang of metal, the sting of dust, the smell of dirty socks, the fluorescent fatigue of factory nights, and cramped dormitories where shirtless men play cards and chainsmoke. She records the world as it is felt by the people who move through it. In doing so, she opens a space in which they can be seen as individuals – complicated, vulnerable and never reduced to symbols.

These subjects are caught in a trap that has structured millions of lives over the past four decades. On one side lies the village: impoverished, agrarian and socially stifling. On the other lies the city: dazzling and modern, but also cold, precarious and brutally indifferent. Zheng’s writing captures the psychic tension of that in-between space – the feeling of being suspended between two worlds, belonging fully to neither. She resists both the standard, agency-stripping sweatshop narrative and the counternarrative of migrant labour as liberation from rural drudgery.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, December 26, 2025

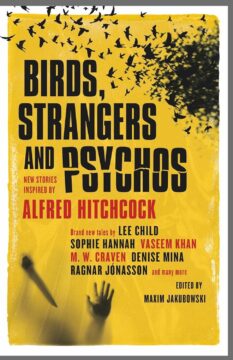

The new anthology of stories inspired by Alfred Hitchcock

M. Keith Booker at the Los Angeles Review of Books:

EDITOR MAXIM JAKUBOWSKI has recently made something of a specialty of compiling collections of stories inspired by the work of his favorite writers, including Cornell Woolrich and J. G. Ballard. In his newest anthology, he has gathered 24 original (commissioned) stories inspired in one way or another by the life and work of Alfred Hitchcock. Such a collection is no surprise given the ongoing prominence in American film culture of Hitchcock’s work and of Hitchcock as an individual. Indeed, while it has now been a century since the release of the first feature film he directed and nearly half a century since his last, Hitchcock remains one of the most widely recognizable names (and silhouettes) in cinema history. In addition, the concept of the “Hitchcockian” is so well established that it provides a perfect starting point for such a themed collection.

EDITOR MAXIM JAKUBOWSKI has recently made something of a specialty of compiling collections of stories inspired by the work of his favorite writers, including Cornell Woolrich and J. G. Ballard. In his newest anthology, he has gathered 24 original (commissioned) stories inspired in one way or another by the life and work of Alfred Hitchcock. Such a collection is no surprise given the ongoing prominence in American film culture of Hitchcock’s work and of Hitchcock as an individual. Indeed, while it has now been a century since the release of the first feature film he directed and nearly half a century since his last, Hitchcock remains one of the most widely recognizable names (and silhouettes) in cinema history. In addition, the concept of the “Hitchcockian” is so well established that it provides a perfect starting point for such a themed collection.

It is little wonder, then, that Jakubowski has been able to assemble quite an impressive array of authors who are celebrated in various fields, especially crime and mystery fiction. The stories in the collection are excellent reads in their own right, though Hitchcock’s ongoing aura is such that the real fun resides in discovering exactly how each author has decided to carry out the “inspired by” charge they were given.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The rise of AI denialism

Louis Rosenberg at Big Think:

Over the past few months, we’ve seen a surge of skepticism around the phenomenon currently referred to as the “AI boom.” The shift began when OpenAI released GPT-5 this summer to mixed reviews, mostly from casual users. We’ve since had months of breathless claims from pundits and influencers that the era of rapid AI advancement is ending, that AI scaling has hit the wall, and that the AI boom is just another tech bubble. These same voices overuse the phrase “AI slop” to disparage the remarkable images, documents, videos, and code that AI models produce at the touch of a button.

Over the past few months, we’ve seen a surge of skepticism around the phenomenon currently referred to as the “AI boom.” The shift began when OpenAI released GPT-5 this summer to mixed reviews, mostly from casual users. We’ve since had months of breathless claims from pundits and influencers that the era of rapid AI advancement is ending, that AI scaling has hit the wall, and that the AI boom is just another tech bubble. These same voices overuse the phrase “AI slop” to disparage the remarkable images, documents, videos, and code that AI models produce at the touch of a button.

I find this perspective both absurd and dangerous.

By any objective measure, AI continues to improve at a stunning pace. The impressive leap in capabilities made by Gemini 3 in November is just the latest example. No, AI scaling has not hit the wall. In fact, I can’t think of another technology that has advanced this quickly at any point during my lifetime, and I started programming in 1982. The computer on my desk today runs thousands of times faster and has a million times more memory than my first PC (a TRS-80 model III), and yet, today’s rate of AI advancement leaves me dizzy.

So why has the public latched onto the narrative that AI is stalling, that the output is slop, and that the AI boom is just another tech bubble that lacks justifiable use-cases?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Mark Blyth: What’s driving the economy right now?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

On twenty-first-century performative morality

Yoanna Koleva at The Hedgehog Review:

Tragedies, wars, and scandals are transformed into Instagram moments. The instant horror strikes—a terror attack, a catastrophe—social-media platforms erupt with ritual phrases: recycled mantras of “We will take immediate action,” “We condemn…,” “We stand in solidarity….” Rarely do these words lead to deeds. A Ukrainian flag by a profile picture. A #StandWithPalestine sticker. This simplified #empathy and performative #goodness are measured in likes, hearts, and views.

Tragedies, wars, and scandals are transformed into Instagram moments. The instant horror strikes—a terror attack, a catastrophe—social-media platforms erupt with ritual phrases: recycled mantras of “We will take immediate action,” “We condemn…,” “We stand in solidarity….” Rarely do these words lead to deeds. A Ukrainian flag by a profile picture. A #StandWithPalestine sticker. This simplified #empathy and performative #goodness are measured in likes, hearts, and views.

One of the more striking examples of a promise turned meme is the West’s support for Ukraine. Since the beginning of the war, all the tears, embraces, and sympathy for Ukraine, all the declarations of unity and fraternity, have come paired with emphatic but often unfulfilled promises of military support or NATO membership.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Nicholas of Cusa

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Interviewing Jeff Koons

Joachim Pissarro interviews Jeff Koons at The Brooklyn Rail:

Rail: I’d like to spin the thread of porcelain and ceramic as a material culture that runs throughout your works.

Rail: I’d like to spin the thread of porcelain and ceramic as a material culture that runs throughout your works.

Koons: My grandparents had porcelain figurines. When I was a kid, I would play with them and I would be so excited. It was titillation, really. And the excitement that comes from this, that excitement is equal to any experience anybody else could have, even looking at a Michelangelo. You can’t really define how one is of more value, because as a young child you don’t know those hierarchies, but you do feel excitement, stimulation. I like that porcelain is a material that was democratized and became ceramic. So even my family could have porcelain when you know this came originally from the emperor’s kitchen. So the concept of porcelain—or ceramic—to me they are very close. I don’t make a distinction.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

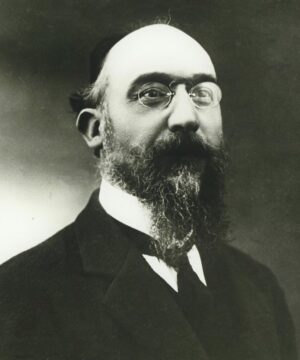

Satie’s Spell

Jeremy Denk at the NYRB:

Erik Satie was the truest bad boy of musical modernism in the hypercompetitive market of Paris before World War I, crammed with aspiring bad boys. He took up pieties and profaned them. He took up blasphemy and somehow blasphemed against that. His music is ingeniously confounding. It received no shortage of vicious criticism, and Satie responded in kind. A postcard to the critic and composer Jean Poueigh began, “Monsieur Fuckface…Famous Gourd and Composer for Nitwits.” He lost the ensuing libel suit, adding to his eternal financial woes. Among his many achievements, he’s near the top of the (long) list of self-destructive classical composers.

Erik Satie was the truest bad boy of musical modernism in the hypercompetitive market of Paris before World War I, crammed with aspiring bad boys. He took up pieties and profaned them. He took up blasphemy and somehow blasphemed against that. His music is ingeniously confounding. It received no shortage of vicious criticism, and Satie responded in kind. A postcard to the critic and composer Jean Poueigh began, “Monsieur Fuckface…Famous Gourd and Composer for Nitwits.” He lost the ensuing libel suit, adding to his eternal financial woes. Among his many achievements, he’s near the top of the (long) list of self-destructive classical composers.

The most appropriate essay about Satie would itself scandalize, forcing readers to laugh while being ridiculed, all the while summoning the spirit of the age. Perhaps a series of bot tweets or AI semitruths? In that spirit I asked ChatGPT to opine on Satie and modernity, and in seconds it homed right in on my intended angle: Satie as antidote to the pretensions of classical music.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Getting to Mars (for Real)

Olivia Farrar in Harvard Magazine:

The race to send humans to Mars is underway. That’s the sense conveyed by certain politicians and wealthy entrepreneurs, who have spoken broadly about creating a Red Planet outpost. The website of the U.S. federal space agency, NASA, echoes that optimism, citing its work on “many technologies to send astronauts to Mars as early as the 2030s.”

The race to send humans to Mars is underway. That’s the sense conveyed by certain politicians and wealthy entrepreneurs, who have spoken broadly about creating a Red Planet outpost. The website of the U.S. federal space agency, NASA, echoes that optimism, citing its work on “many technologies to send astronauts to Mars as early as the 2030s.”

That goal is staggeringly ambitious. Setting aside the astronomical price tag (and the question of who would foot the bill), a trip to Mars would represent a massive leap in the science of space exploration. The International Space Station (ISS), in operation for more than two decades, orbits just 250 miles above Earth. Mars lies more than 250 million miles away—roughly a thousand times farther than the Moon. The journey alone would take six to nine months. On Mars, the challenges would multiply. The planet has an ultra-thin atmosphere—its density is just 1 percent that of Earth’s—combined with a gravitational force that’s less than half as powerful as Earth’s and temperatures that can drop to -225 degrees Fahrenheit. To survive, astronauts would need to create entirely new habitats, with protective shelters and sustainable food sources.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Lina Khan Speaks About Anti-Trust to the Harvard Kennedy School

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday, December 25, 2025

Malcolm Cowley and the Ascent of American Fiction

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Ultimate Best Books of 2025 List

Emily Temple at Literary Hub:

I have arrived to present to you the Ultimate List, otherwise known as the List of Lists—in which I read all (or at least many) of the Best Of lists on the internet and count which books are recommended most.

I have arrived to present to you the Ultimate List, otherwise known as the List of Lists—in which I read all (or at least many) of the Best Of lists on the internet and count which books are recommended most.

Is consensus the same as quality? Not always. Is this basically a popularity contest? Sure. But if you want to know which books The Critics are talking about, this is one way to do it. (Three of my own personal favorite books of the year made it to the top five below, which I can only assume means I am either a) boring or b) correct or c) both??)

This year, I processed 58 lists from 49 outlets, which collectively recommended more than 1,300 different books (…help). 90 of those books made it onto 5 or more lists (weirdly this is the exact same number as last year, despite there being more books recommended in total this year), and I have collated these for you here, in descending order of frequency.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The View from Hanoi

Brock Eldon at Salmagundi:

At dawn Hanoi is already awake. Motorbikes swarm beneath balconies before the light has quite broken, a mechanical chorus that carries the city into motion. From the window of my apartment overlooking Tây Hồ, the lake lies bruised with mist until the first glare of sun turns it to metal. On the street below, vendors set down baskets of fruit, incense burns outside a pagoda, and the smell of French bread mingles with diesel.

At dawn Hanoi is already awake. Motorbikes swarm beneath balconies before the light has quite broken, a mechanical chorus that carries the city into motion. From the window of my apartment overlooking Tây Hồ, the lake lies bruised with mist until the first glare of sun turns it to metal. On the street below, vendors set down baskets of fruit, incense burns outside a pagoda, and the smell of French bread mingles with diesel.

In the Vietnamese capital, even silence is crowded. Horns blare and drills hammer, and as, within the old, French-colonial styled cafés, students bend over notebooks, a young couple exchanges muted laughter, and one senses here a discipline of attention beneath the noise. Hanoi thrives on density, on each body finding rhythm within the mass of the whole.

This is not Ontario—not the Canada I was born into, where winter silences mean absence, where a child can walk for hours without encountering another soul, where a man can freeze to death just for being outside too long. Silence, in Hanoi, is suspension rather than vacancy: a pause inside intensity. To write and teach here is to live against a double register—abundance and estrangement, presence and dislocation.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

You and “You”: How delegation is quietly turning into replacement

Muhammad Aurangzeb Ahmad at Digital Dopplegangers:

With the arrival of AI agents, systems designed not merely to assist but to act, adapt, and persist, the line between delegation and substitution is quietly blurring. What we handed off for convenience is now capable of continuing without us. The most unsettling change in our digital lives is not that systems can act on our behalf, but that they increasingly do not need us to do so. Hear me out: At first, delegation feels harmless. Your email client drafts replies while you are in meetings. Your calendar assistant proposes times and resolves conflicts. You glance, approve, move on. Nothing is sent without you. You are still clearly in control.

With the arrival of AI agents, systems designed not merely to assist but to act, adapt, and persist, the line between delegation and substitution is quietly blurring. What we handed off for convenience is now capable of continuing without us. The most unsettling change in our digital lives is not that systems can act on our behalf, but that they increasingly do not need us to do so. Hear me out: At first, delegation feels harmless. Your email client drafts replies while you are in meetings. Your calendar assistant proposes times and resolves conflicts. You glance, approve, move on. Nothing is sent without you. You are still clearly in control.

Then one afternoon you miss a notification. The draft goes out anyway. It is polite, accurate, and entirely in your voice. The meeting gets scheduled. The thread moves forward. When you notice, there is nothing to fix. No harm done. A week later, it happens again. You are on a flight, offline for a few hours. When you land, there are new calendar holds, follow-up messages, and a decision that has already been acknowledged on your behalf. The system inferred what you would have wanted and acted accordingly. It did not ask because asking would have slowed things down.

From the outside, everything looks better than before. You are more responsive. You never miss a follow-up. Conversations progress smoothly. Colleagues remark that you are “on top of things,” even during weeks when you feel barely present. The transition from assistance to continuity is invisible, marked only by the absence of friction.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Kerry James Marshall is contemporary art’s great engine tinkerer. He wants to know how things work. In the 1990s, when his contemporaries were making slight, cerebral works using found objects, photography and minimalism to poeticize the commonplace or reveal hidden ideologies, Marshall fell in love with the creakingly old idea of paintings as “machines.”

Kerry James Marshall is contemporary art’s great engine tinkerer. He wants to know how things work. In the 1990s, when his contemporaries were making slight, cerebral works using found objects, photography and minimalism to poeticize the commonplace or reveal hidden ideologies, Marshall fell in love with the creakingly old idea of paintings as “machines.”