Ben Brubaker in Quanta:

How do you prove something is true? For mathematicians, the answer is simple: Start with some basic assumptions and proceed, step by step, to the conclusion. QED, proof complete. If there’s a mistake anywhere, an expert who reads the proof carefully should be able to spot it. Otherwise, the proof must be valid. Mathematicians have been following this basic approach for well over 2,000 years.

How do you prove something is true? For mathematicians, the answer is simple: Start with some basic assumptions and proceed, step by step, to the conclusion. QED, proof complete. If there’s a mistake anywhere, an expert who reads the proof carefully should be able to spot it. Otherwise, the proof must be valid. Mathematicians have been following this basic approach for well over 2,000 years.

Then, in the 1980s and 1990s, computer scientists reimagined what a proof could be. They developed a dizzying variety of new approaches, and when the dust settled, two inventions loomed especially large: zero-knowledge proofs, which can convince a skeptic that a statement is true without revealing why it is true, and probabilistically checkable proofs, which can persuade a reader of the truth of a proof even if they only see a few tiny snippets of it.

“These are, to me, two of the most beautiful notions in all of theoretical computer science,” said Tom Gur(opens a new tab), a computer scientist at the University of Cambridge.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The press and especially the news channels are constantly warning us that antisemitism is everywhere on the rise. They don’t point to specific episodes, content instead to denounce an ancient prejudice that in the context of a Middle East crisis is staging a resurgence. No, they describe a gigantic wave of antisemitism that has been sweeping across the globe since October 7. Its epicenter is on American college campuses, just as the epicenter of the anti–Vietnam War movement was on college campuses sixty years ago.

The press and especially the news channels are constantly warning us that antisemitism is everywhere on the rise. They don’t point to specific episodes, content instead to denounce an ancient prejudice that in the context of a Middle East crisis is staging a resurgence. No, they describe a gigantic wave of antisemitism that has been sweeping across the globe since October 7. Its epicenter is on American college campuses, just as the epicenter of the anti–Vietnam War movement was on college campuses sixty years ago. At a time of widespread economic distress, ethnonationalists in the United States and United Kingdom as well as Germany, France, Hungary, Poland and Italy are united by their antipathy to immigrants, and targeting of institutions deemed insufficiently patriotic or indulgent of sexual, ethnic and racial minorities. This bleak scenario can be further elaborated. The main economic ideologies of endless growth and global prosperity have come up against environmental constraints and technological innovation, as well as built-in limits, and look unsustainable.

At a time of widespread economic distress, ethnonationalists in the United States and United Kingdom as well as Germany, France, Hungary, Poland and Italy are united by their antipathy to immigrants, and targeting of institutions deemed insufficiently patriotic or indulgent of sexual, ethnic and racial minorities. This bleak scenario can be further elaborated. The main economic ideologies of endless growth and global prosperity have come up against environmental constraints and technological innovation, as well as built-in limits, and look unsustainable. Like her other works—including Sister Deborah, the English translation of which is forthcoming from Archipelago later this month—Cockroaches is a reckoning with history, a steadfast commemoration of a community and culture that others tried to eradicate. But even in her debut, which many early critics read as a straightforward work of testimony about the Tutsi genocide, there is a deeply self-questioning quality to that work of commemoration. The narrator always wakes from her nightmare just as she is about to perish at the hands of her pursuers, who have already killed the other Tutsi girls fleeing alongside her. She thinks, “I know I’m going to fall, I’m going to be trampled”; and yet each night she reopens her eyes and her surroundings contradict this conviction. Why was she chosen to survive, and who did the choosing?

Like her other works—including Sister Deborah, the English translation of which is forthcoming from Archipelago later this month—Cockroaches is a reckoning with history, a steadfast commemoration of a community and culture that others tried to eradicate. But even in her debut, which many early critics read as a straightforward work of testimony about the Tutsi genocide, there is a deeply self-questioning quality to that work of commemoration. The narrator always wakes from her nightmare just as she is about to perish at the hands of her pursuers, who have already killed the other Tutsi girls fleeing alongside her. She thinks, “I know I’m going to fall, I’m going to be trampled”; and yet each night she reopens her eyes and her surroundings contradict this conviction. Why was she chosen to survive, and who did the choosing? Suppose you want to be a better person. (Lots of us do.) How might you go about it? You might try to become more generous and commit to donating more of your income to charity. Or you might try to become more patient, and practise listening to your partner, instead of snapping at them. These commonsense prescriptions invoke an ancient ethical tradition. Generosity and patience are virtues – excellences of character, whose exercise makes us flourish. To live well, says the virtue ethicist, is to cultivate and exercise just such excellences of character.

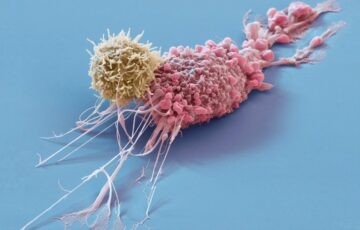

Suppose you want to be a better person. (Lots of us do.) How might you go about it? You might try to become more generous and commit to donating more of your income to charity. Or you might try to become more patient, and practise listening to your partner, instead of snapping at them. These commonsense prescriptions invoke an ancient ethical tradition. Generosity and patience are virtues – excellences of character, whose exercise makes us flourish. To live well, says the virtue ethicist, is to cultivate and exercise just such excellences of character. One woman and two men with severe autoimmune conditions have gone into remission after being treated with bioengineered and CRISPR-modified immune cells

One woman and two men with severe autoimmune conditions have gone into remission after being treated with bioengineered and CRISPR-modified immune cells Scientists discovered that bacteria commonly found in wastewater can break down plastic to turn it into a food source, a finding that researchers hope could be a promising answer to combat one of Earth’s major pollution problems. In a

Scientists discovered that bacteria commonly found in wastewater can break down plastic to turn it into a food source, a finding that researchers hope could be a promising answer to combat one of Earth’s major pollution problems. In a

The Nobel prize has been awarded in three scientific fields —

The Nobel prize has been awarded in three scientific fields —