James Campbell at The New Criterion:

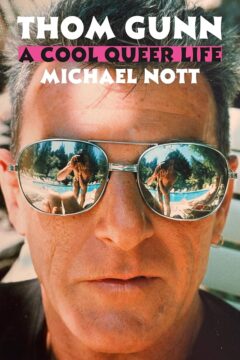

I first met Thom Gunn in 1997 and last saw him in London in 2003, a year before his death. I’m not fool enough to contradict Nott and his well-informed witnesses, and maybe I was simply blinded time and again by Gunn’s charisma, but to me he was not the desolate figure who moves through the dismal second half of A Cool Queer Life. We sat for an entire afternoon on our first encounter in his house on Cole Street, me with his cat on my lap (immortalized in the poem “In Trust” from his last book, Boss Cupid) and a bottle of cheap white wine between us. (It had to be cheap: refined in so many ways, Gunn loved vulgarity in drink and music. “I like loud music, bars, and boisterous men,” he wrote in The Passages of Joy.) It counts as one of the most memorable conversations of my life. At intervals, he would rise to take down a book from the shelf, to read a poem in order to illustrate or affirm an enthusiasm. I remember him saying that he had a direct entry into poetry. Where he encountered barriers, he usually knew how to overcome them. He believed that Boss Cupid would be his final book, but his illuminating introduction to a short selection from Ezra Pound made in 2000 proves that his “writing life” continued in other forms.

I first met Thom Gunn in 1997 and last saw him in London in 2003, a year before his death. I’m not fool enough to contradict Nott and his well-informed witnesses, and maybe I was simply blinded time and again by Gunn’s charisma, but to me he was not the desolate figure who moves through the dismal second half of A Cool Queer Life. We sat for an entire afternoon on our first encounter in his house on Cole Street, me with his cat on my lap (immortalized in the poem “In Trust” from his last book, Boss Cupid) and a bottle of cheap white wine between us. (It had to be cheap: refined in so many ways, Gunn loved vulgarity in drink and music. “I like loud music, bars, and boisterous men,” he wrote in The Passages of Joy.) It counts as one of the most memorable conversations of my life. At intervals, he would rise to take down a book from the shelf, to read a poem in order to illustrate or affirm an enthusiasm. I remember him saying that he had a direct entry into poetry. Where he encountered barriers, he usually knew how to overcome them. He believed that Boss Cupid would be his final book, but his illuminating introduction to a short selection from Ezra Pound made in 2000 proves that his “writing life” continued in other forms.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

But if there was little obvious distinction between “religious” pilgrims and “regular” travelers, it was partly because the discourse of contemporary travel is so often geared toward the same ends as pilgrimage proper: a journey that results in the transformation, and ideally purification, of the searching self. This is the goal underlying, for example, travel-as-transformation narratives like Cheryl Strayed’s Wild, an account of the author’s solo hike along the Pacific Crest Trail, and Elizabeth Gilbert’s divorce-and-self-actualization memoir Eat, Pray, Love. Travel, at least the kind of travel so often coded as “real” or “authentic” (as opposed to, say, the family resort vacation, the Instagram trip, or the perfunctory list-ticking of the much-derided “tourist”), is already treated as a kind of secular pilgrimage in which we find out who we really are only by untethering ourselves from those elements of our identities too closely linked to habit and home. Only when we are away from our daily routines, this ideology implies, from our bosses and spouses and children, when we are challenged by language barrier or public transit mishap or unexpected romantic chemistry, can we come to know who we really are.

But if there was little obvious distinction between “religious” pilgrims and “regular” travelers, it was partly because the discourse of contemporary travel is so often geared toward the same ends as pilgrimage proper: a journey that results in the transformation, and ideally purification, of the searching self. This is the goal underlying, for example, travel-as-transformation narratives like Cheryl Strayed’s Wild, an account of the author’s solo hike along the Pacific Crest Trail, and Elizabeth Gilbert’s divorce-and-self-actualization memoir Eat, Pray, Love. Travel, at least the kind of travel so often coded as “real” or “authentic” (as opposed to, say, the family resort vacation, the Instagram trip, or the perfunctory list-ticking of the much-derided “tourist”), is already treated as a kind of secular pilgrimage in which we find out who we really are only by untethering ourselves from those elements of our identities too closely linked to habit and home. Only when we are away from our daily routines, this ideology implies, from our bosses and spouses and children, when we are challenged by language barrier or public transit mishap or unexpected romantic chemistry, can we come to know who we really are. T

T Human life expectancy dramatically increased last century. Compared to babies born in 1900, those born at the turn of the 21st century could live, on average, three decades longer—

Human life expectancy dramatically increased last century. Compared to babies born in 1900, those born at the turn of the 21st century could live, on average, three decades longer— It is midday on a Friday, and I am in a room with about a dozen teenagers at an international school in Oslo, Norway. We are talking about how and why they use TikTok, the digital video-sharing application. The prevailing mood is laid-back: though I am technically a media researcher, and they are technically my research participants, this group of 16- and 17-year-olds are joking around with each other and with me as we chat about the role of TikTok in their everyday lives. It’s a beautiful day – warm and summery – and everyone, including me, is in a fun weekend mood.

It is midday on a Friday, and I am in a room with about a dozen teenagers at an international school in Oslo, Norway. We are talking about how and why they use TikTok, the digital video-sharing application. The prevailing mood is laid-back: though I am technically a media researcher, and they are technically my research participants, this group of 16- and 17-year-olds are joking around with each other and with me as we chat about the role of TikTok in their everyday lives. It’s a beautiful day – warm and summery – and everyone, including me, is in a fun weekend mood. Terence Tao snorts and waves his hands dismissively when he hears that he is the most intelligent human being on the planet, according to a number of online rankings, including a recent one conducted by the

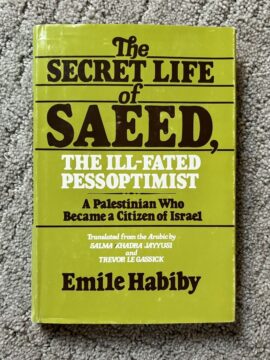

Terence Tao snorts and waves his hands dismissively when he hears that he is the most intelligent human being on the planet, according to a number of online rankings, including a recent one conducted by the  The Palestinian Nakba produced, alongside death and displacement, a generation of writers who came of age in its aftermath. The moment seemed to demand a funereal tone from artists who had witnessed the tragedy. For them, a version of Theodor Adorno’s maxim, that to “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric,” rung true. Few broke the taboo.

The Palestinian Nakba produced, alongside death and displacement, a generation of writers who came of age in its aftermath. The moment seemed to demand a funereal tone from artists who had witnessed the tragedy. For them, a version of Theodor Adorno’s maxim, that to “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric,” rung true. Few broke the taboo.

It’s not immoral to kick a rock; it is immoral to kick a baby. At what point do we start saying that it is wrong to cause pain to something? This question has less to do with “consciousness” and more to do with “sentience” — the ability to perceive feelings and sensations. Philosopher Jonathan Birch has embarked on a careful study of the meaning of sentience and how it can be identified in different kinds of organisms, as he discusses in his new open-access book

It’s not immoral to kick a rock; it is immoral to kick a baby. At what point do we start saying that it is wrong to cause pain to something? This question has less to do with “consciousness” and more to do with “sentience” — the ability to perceive feelings and sensations. Philosopher Jonathan Birch has embarked on a careful study of the meaning of sentience and how it can be identified in different kinds of organisms, as he discusses in his new open-access book  For Christmas lunch, 1937, Virginia and Leonard Woolf hosted John Maynard Keynes and his wife, Lydia. Imagine the talk, which no doubt ranged widely, including gossip about younger writers like W. H. Auden, the recipient that autumn of the King’s Gold Medal for Poetry from George VI himself. A lot of people were saying it: Auden was the man to watch. At only thirty, he was already regarded as England’s leading poet, head of a squadron of younger writers, including Louis MacNeice, C. Day-Lewis and Stephen Spender. According to Nicholas Jenkins’ important new book, The Island: War and Belonging in Auden’s England,

For Christmas lunch, 1937, Virginia and Leonard Woolf hosted John Maynard Keynes and his wife, Lydia. Imagine the talk, which no doubt ranged widely, including gossip about younger writers like W. H. Auden, the recipient that autumn of the King’s Gold Medal for Poetry from George VI himself. A lot of people were saying it: Auden was the man to watch. At only thirty, he was already regarded as England’s leading poet, head of a squadron of younger writers, including Louis MacNeice, C. Day-Lewis and Stephen Spender. According to Nicholas Jenkins’ important new book, The Island: War and Belonging in Auden’s England, THERE’S A REASON why so many people regard Ronald Reagan as America’s last great leader. The further the monolithic Hollywood of the storied past recedes into the fragmented fun house of the media present, the more mythic the stellar avatars appear. One such divinity: straight-talking, honorable, unassuming, heroic Henry Fonda (1905–1982).

THERE’S A REASON why so many people regard Ronald Reagan as America’s last great leader. The further the monolithic Hollywood of the storied past recedes into the fragmented fun house of the media present, the more mythic the stellar avatars appear. One such divinity: straight-talking, honorable, unassuming, heroic Henry Fonda (1905–1982). How does the brain

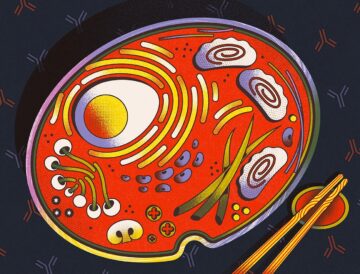

How does the brain Reboot your immune system with intermittent fasting. Help your ‘good’ bacteria to thrive with a plant-based diet. Move over morning coffee: mushroom tea could bolster your anticancer defences. Claims such as these, linking health, diet and immunity, bombard supermarket shoppers and pervade the news. Beyond the headlines and product labels, the scientific foundations of many such claims are often based on limited evidence. That’s partly because conducting rigorous studies to track what people eat and the impact of diet

Reboot your immune system with intermittent fasting. Help your ‘good’ bacteria to thrive with a plant-based diet. Move over morning coffee: mushroom tea could bolster your anticancer defences. Claims such as these, linking health, diet and immunity, bombard supermarket shoppers and pervade the news. Beyond the headlines and product labels, the scientific foundations of many such claims are often based on limited evidence. That’s partly because conducting rigorous studies to track what people eat and the impact of diet  The car I bought in Hamburg had distinctive oval German export license plates, and an international registration sticker marked with a D, for Deutschland. As I drove through Holland on my way to Paris, more than once when asking for directions I received dirty looks, especially from older persons for whom the wartime German occupation was a living memory.

The car I bought in Hamburg had distinctive oval German export license plates, and an international registration sticker marked with a D, for Deutschland. As I drove through Holland on my way to Paris, more than once when asking for directions I received dirty looks, especially from older persons for whom the wartime German occupation was a living memory. In The Oxford Book of Modern Science Writing (2008), Richard Dawkins writes:

In The Oxford Book of Modern Science Writing (2008), Richard Dawkins writes: Why are some countries richer than others? The 2024 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel has been awarded to three researchers who have helped shed light on this fundamental question.

Why are some countries richer than others? The 2024 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel has been awarded to three researchers who have helped shed light on this fundamental question. J

J