Lily Lynch in Sidecar:

Austria’s far-right Freedom Party (FPÖ) – the indirect successor to Austria’s National Socialist German Workers’ Party – used to generate apocalyptic headlines. Its successes were once treated as major news stories on both sides of the Atlantic, especially when the party was led by the telegenic Jörg Haider. A generational political talent, he led a campaign to force a referendum on restricting immigration in 1993 and pioneered a tanned, yuppy brand of right-wing politics that looks awfully familiar these days. Prior to Haider taking the helm in 1986, the FPÖ was a traditional bourgeois party dominated by decrepit Nazis and stodgy pan-German nationalists. But under his leadership, it was transformed into a modern populist outfit fuelled by xenophobia and entertainment. Haider, the New York Times magazine noted in 2000, ‘knows the glib, politics-as-pop-culture temper of his times’. ‘Europe, land of ghosts, is aghast.’

The Carinthian multi-millionaire was Austria’s wealthiest politician but styled himself a champion of the people, comfortable in the company of both the Viennese bourgeoisie and the clientele of rural beer halls. He poached support from the Socialist Party’s (SPÖ) traditional base with his economic populism, but was most successful with the middle class, who, in the years approaching the new millennium, feared losing jobs, status and state welfare as a result of immigration, European Union membership and globalization. The party’s dramatic metamorphosis under Haider was a spectacular electoral success, with results in the double digits and rising throughout the 90s. In 2000, having secured 27%, they entered government in coalition with the conservative Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP), upending the country’s post-war political consensus, which had been built on the joint dominance of the ÖVP and SPÖ.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

At

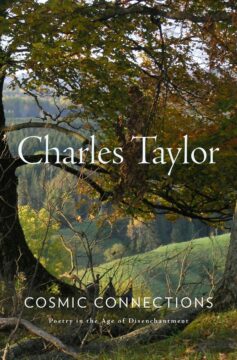

At  This summer, Ayad Akhtar was struggling with the final scene of “McNeal,” his knotty and disorienting play about a Nobel Prize-winning author who uses artificial intelligence to write a novel. He wanted the title character, played by Robert Downey Jr. in his Broadway debut, to deliver a monologue that sounded like a computer wrote it. So Akhtar uploaded what he had written into ChatGPT, gave the program a list of words, and told it to produce a speech in the style of Shakespeare. The results were so compelling that he read the speech to the cast at the next rehearsal.

This summer, Ayad Akhtar was struggling with the final scene of “McNeal,” his knotty and disorienting play about a Nobel Prize-winning author who uses artificial intelligence to write a novel. He wanted the title character, played by Robert Downey Jr. in his Broadway debut, to deliver a monologue that sounded like a computer wrote it. So Akhtar uploaded what he had written into ChatGPT, gave the program a list of words, and told it to produce a speech in the style of Shakespeare. The results were so compelling that he read the speech to the cast at the next rehearsal. The passage from Enlightenment to Romanticism at the end of the eighteenth century was perhaps the most deeply felt crisis in European intellectual history. The Age of Reason had seen such extraordinary strides in scientific discovery and political liberty that the future progress of both mind and society seemed to many already marked out. Two groups of people were unhappy about this. Traditionalists, both religious and political, regarded the party of Reason as a nuisance, to be swatted away rather than argued with in earnest. The Enlightenment’s scientific materialism and anti-authoritarianism seemed to them sheer perversity, old heresies in a new garb. But by the time the party of Reason morphed into the party of Revolution, it was too late for swatting; and by the mid-nineteenth century the traditionalists had retreated into a long defensive crouch that lasted until quite recently.

The passage from Enlightenment to Romanticism at the end of the eighteenth century was perhaps the most deeply felt crisis in European intellectual history. The Age of Reason had seen such extraordinary strides in scientific discovery and political liberty that the future progress of both mind and society seemed to many already marked out. Two groups of people were unhappy about this. Traditionalists, both religious and political, regarded the party of Reason as a nuisance, to be swatted away rather than argued with in earnest. The Enlightenment’s scientific materialism and anti-authoritarianism seemed to them sheer perversity, old heresies in a new garb. But by the time the party of Reason morphed into the party of Revolution, it was too late for swatting; and by the mid-nineteenth century the traditionalists had retreated into a long defensive crouch that lasted until quite recently. Beginning in late September,

Beginning in late September,  In May 2018, Childish Gambino (Donald Glover’s musical alter-ego) dropped the single

In May 2018, Childish Gambino (Donald Glover’s musical alter-ego) dropped the single  I

I Ever since the first blood-forming stem cells were successfully transplanted into people with blood cancers more than 50 years ago, researchers have wondered whether they developed

Ever since the first blood-forming stem cells were successfully transplanted into people with blood cancers more than 50 years ago, researchers have wondered whether they developed  THE YEAR IS 1906. Theodore Roosevelt is in the White House. In New York, the newspapers are reporting on the political aspirations of William Randolph Hearst, unrest in Russia, and the latest dividends from US Steel. Scientific American is running articles about exploring the Sargasso Sea. In Boston, The New England Journal of Medicine is discussing new treatments for typhus and tuberculosis. Upton Sinclair’s new novel The Jungle, recently out from Doubleday, portrays the oppressive working conditions in Chicago’s meatpacking industry—Jack London calls it “the Uncle Tom’s Cabin of wage slavery”—and it’s taking the country by storm. In October, the Chicago White Sox play the Cubs in the country’s first intracity World Series, which the Sox go on to win (in a massive upset) four games to two.

THE YEAR IS 1906. Theodore Roosevelt is in the White House. In New York, the newspapers are reporting on the political aspirations of William Randolph Hearst, unrest in Russia, and the latest dividends from US Steel. Scientific American is running articles about exploring the Sargasso Sea. In Boston, The New England Journal of Medicine is discussing new treatments for typhus and tuberculosis. Upton Sinclair’s new novel The Jungle, recently out from Doubleday, portrays the oppressive working conditions in Chicago’s meatpacking industry—Jack London calls it “the Uncle Tom’s Cabin of wage slavery”—and it’s taking the country by storm. In October, the Chicago White Sox play the Cubs in the country’s first intracity World Series, which the Sox go on to win (in a massive upset) four games to two. In various ways, Pedro Almodóvar’s terrific new film represents a culmination or point of arrival. The Room Next Door, winner of the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, marks the director’s first time working in English and telling a story set entirely outside Spain. It is also a clear admission – from a film-maker strongly associated with costume, production design and bodies – of an essential bookishness: his belief, expressed in his recently published collection of stories The Last Dream, that his vocation is “literary”, and it’s merely a quirk of fate that the bulk of his written output has been 22 screenplays, which he also directed. The film concerns two writers, Ingrid, a war reporter suffering from cancer (Tilda Swinton), and Martha (Julianne Moore), a novelist with whom Ingrid spends her final weeks. Though Almodóvar does away with many of the reference points in the source material, Sigrid Nunez’s novel What Are You Going Through, he introduces plenty of his own. The Room Next Door opens at a Manhattan bookshop, where Martha is doing a signing, and ends with a quotation from “The Dead” – and it isn’t the only bookshop, or mention of James Joyce.

In various ways, Pedro Almodóvar’s terrific new film represents a culmination or point of arrival. The Room Next Door, winner of the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, marks the director’s first time working in English and telling a story set entirely outside Spain. It is also a clear admission – from a film-maker strongly associated with costume, production design and bodies – of an essential bookishness: his belief, expressed in his recently published collection of stories The Last Dream, that his vocation is “literary”, and it’s merely a quirk of fate that the bulk of his written output has been 22 screenplays, which he also directed. The film concerns two writers, Ingrid, a war reporter suffering from cancer (Tilda Swinton), and Martha (Julianne Moore), a novelist with whom Ingrid spends her final weeks. Though Almodóvar does away with many of the reference points in the source material, Sigrid Nunez’s novel What Are You Going Through, he introduces plenty of his own. The Room Next Door opens at a Manhattan bookshop, where Martha is doing a signing, and ends with a quotation from “The Dead” – and it isn’t the only bookshop, or mention of James Joyce. Tyler Cowen is an economics professor and blogger at

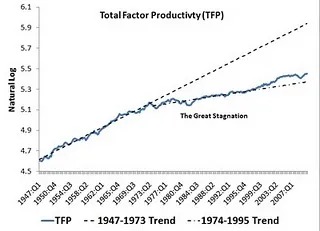

Tyler Cowen is an economics professor and blogger at