Noah Smith at Noahpinion:

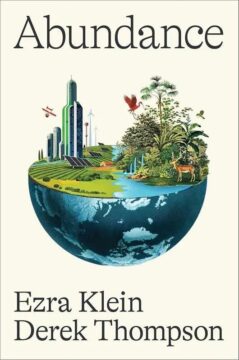

I’ve been waiting a long time for this book. Late in 2021, Ezra Klein wrote a New York Times op-ed titled “The Economic Mistake the Left Is Finally Confronting”, in which he called for a new “supply-side progressivism”. Four months later, Derek Thompson wrote an article in The Atlantic titled “A Simple Plan to Solve All of America’s Problems”, in which he called for an “abundance agenda”. Many people quickly recognized that these were essentially the same idea. Klein and Thompson recognized it too, and teamed up to co-author a book that would serve as a manifesto for this new big idea. Three years later, Abundance has hit the stores. It’s a good book, and you should read it.

I’ve been waiting a long time for this book. Late in 2021, Ezra Klein wrote a New York Times op-ed titled “The Economic Mistake the Left Is Finally Confronting”, in which he called for a new “supply-side progressivism”. Four months later, Derek Thompson wrote an article in The Atlantic titled “A Simple Plan to Solve All of America’s Problems”, in which he called for an “abundance agenda”. Many people quickly recognized that these were essentially the same idea. Klein and Thompson recognized it too, and teamed up to co-author a book that would serve as a manifesto for this new big idea. Three years later, Abundance has hit the stores. It’s a good book, and you should read it.

The basic thesis of this book is that liberalism — or progressivism, or the left, etc. — has forgotten how to build the things that people want. Every progressive talks about “affordable housing”, and yet blue cities and blue states build so little housing that it becomes unaffordable. Every progressive talks about the need to fight climate change, and yet environmental regulations have made it incredibly difficult to replace fossil fuels with green energy. Many progressives dream about the days when government could accomplish great things, and post maps of imaginary high-speed rail networks crisscrossing the country, yet various progressive policies have hobbled the government’s ability to build infrastructure.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

I saw Eraserhead in Providence in late 1979, I think, and I suspect it was at the Avon on Thayer Street. I liked cheeseball, poorly-constructed horror films in those days and I think Lynch’s film was being sold as midnight cult film fare, a more horrifying Rocky Horror Picture Show. So I went. At a similar moment, in undergraduate school at Brown University, I was also taking, or had just taken, Keith Waldrop’s survey course on this history of the silent film, which had offered me my first interaction with Bunuel and Dali’s Un Chien Andalou. In my recollection these experiences are utterly conjoined. Like the Bunuel film, Eraserhead scared me very thoroughly—it was merciless and unforgiving and also very funny—and likewise it established in my mind a set of filmic values (for which Un Chien Andalou was also partly responsible), antithetical to the barbarous Hollywood values, and from these I never really strayed: 1) cheap is fine, 2) black and white tells you some things, 3) good sound design is crucial, 4) non-actors are very often better than actors, 5) subjectivity is in a circular container, and thus the reiterations, 6) linearity in storytelling is a con, and 7) when in doubt stick a lady in a radiator and have her sing.

I saw Eraserhead in Providence in late 1979, I think, and I suspect it was at the Avon on Thayer Street. I liked cheeseball, poorly-constructed horror films in those days and I think Lynch’s film was being sold as midnight cult film fare, a more horrifying Rocky Horror Picture Show. So I went. At a similar moment, in undergraduate school at Brown University, I was also taking, or had just taken, Keith Waldrop’s survey course on this history of the silent film, which had offered me my first interaction with Bunuel and Dali’s Un Chien Andalou. In my recollection these experiences are utterly conjoined. Like the Bunuel film, Eraserhead scared me very thoroughly—it was merciless and unforgiving and also very funny—and likewise it established in my mind a set of filmic values (for which Un Chien Andalou was also partly responsible), antithetical to the barbarous Hollywood values, and from these I never really strayed: 1) cheap is fine, 2) black and white tells you some things, 3) good sound design is crucial, 4) non-actors are very often better than actors, 5) subjectivity is in a circular container, and thus the reiterations, 6) linearity in storytelling is a con, and 7) when in doubt stick a lady in a radiator and have her sing. What do the angelic forces of the Heavenly Host have to do with orgasms? The answer, according to the 12th-century philosopher and theologian Maimonides, was simple. Some invisible forces that caused movement could be explained by God working through angels. Quoting a famous rabbi who talked about ‘the angel put in charge of lust’, Maimonides commented that ‘he means to say: the force of orgasm … Thus this force too is called … an angel.’

What do the angelic forces of the Heavenly Host have to do with orgasms? The answer, according to the 12th-century philosopher and theologian Maimonides, was simple. Some invisible forces that caused movement could be explained by God working through angels. Quoting a famous rabbi who talked about ‘the angel put in charge of lust’, Maimonides commented that ‘he means to say: the force of orgasm … Thus this force too is called … an angel.’ There is a phrase

There is a phrase I recently copy-pasted

I recently copy-pasted As anyone who has had the job can attest, the enterprise of being chair of an English department—or, in my case, “head,” a term meant to designate a role still more managerial—comes with more than its share of these scenes of demoralized compliance and low-grade surrender. “A two-fisted engine of aggravation and despair” is how I recently described the gig to a friend, and it’s hard to find anyone who would disagree. So imagine my surprise, my wonder even, in having found for myself a nourishing antidote to all the in-built tedium, joylessness, and metastatic irritation. Yoga? Hypnosis? Ketamine? No. It has appeared in nothing so much as the revelation that my colleagues are, in ways and degrees I hadn’t quite grasped, extraordinarily good at what they do.

As anyone who has had the job can attest, the enterprise of being chair of an English department—or, in my case, “head,” a term meant to designate a role still more managerial—comes with more than its share of these scenes of demoralized compliance and low-grade surrender. “A two-fisted engine of aggravation and despair” is how I recently described the gig to a friend, and it’s hard to find anyone who would disagree. So imagine my surprise, my wonder even, in having found for myself a nourishing antidote to all the in-built tedium, joylessness, and metastatic irritation. Yoga? Hypnosis? Ketamine? No. It has appeared in nothing so much as the revelation that my colleagues are, in ways and degrees I hadn’t quite grasped, extraordinarily good at what they do. We often study cognition in other species, in part to learn about modes of thinking that are different from our own. Today’s guest, psychologist/philosopher Alison Gopnik, argues that we needn’t look that far: human children aren’t simply undeveloped adults, they have a way of thinking that is importantly distinct from that of grownups. Children are explorers with ever-expanding neural connections; adults are exploiters who (they think) know how the world works. These studies have important implications for the training and use of artificial intelligence.

We often study cognition in other species, in part to learn about modes of thinking that are different from our own. Today’s guest, psychologist/philosopher Alison Gopnik, argues that we needn’t look that far: human children aren’t simply undeveloped adults, they have a way of thinking that is importantly distinct from that of grownups. Children are explorers with ever-expanding neural connections; adults are exploiters who (they think) know how the world works. These studies have important implications for the training and use of artificial intelligence. As we observe our current world order becoming less cohesive, more volatile, socially fractured, politically polarized, and hence arguably less predictable, it becomes increasingly difficult to understand why.

As we observe our current world order becoming less cohesive, more volatile, socially fractured, politically polarized, and hence arguably less predictable, it becomes increasingly difficult to understand why. On the wall of his living room in Lier, Belgium, Werner van Beethoven keeps a family tree. Thirteen generations unfurl along its branches, including one that shows his best known relative, born in 1770: Ludwig van Beethoven, who forever redefined Western music with compositions such as the Fifth Symphony, Für Elise, and others. Yet that sprig held a hereditary, and potentially scandalous, secret.

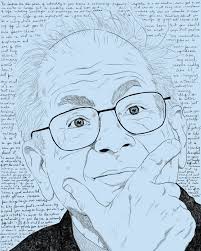

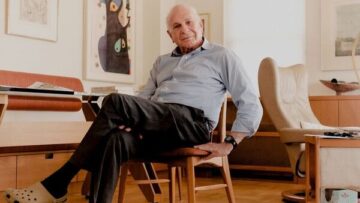

On the wall of his living room in Lier, Belgium, Werner van Beethoven keeps a family tree. Thirteen generations unfurl along its branches, including one that shows his best known relative, born in 1770: Ludwig van Beethoven, who forever redefined Western music with compositions such as the Fifth Symphony, Für Elise, and others. Yet that sprig held a hereditary, and potentially scandalous, secret. In mid-March 2024, Daniel Kahneman flew from New York to Paris with his partner, Barbara Tversky, to unite with his daughter and her family. They spent days walking around the city, going to museums and the ballet, and savoring soufflés and chocolate mousse. Around March 22, Kahneman, who had turned 90 that month, also started emailing a personal message to several dozen of the people he was closest to. On March 26, Kahneman left his family and flew to Switzerland. His email explained why:

In mid-March 2024, Daniel Kahneman flew from New York to Paris with his partner, Barbara Tversky, to unite with his daughter and her family. They spent days walking around the city, going to museums and the ballet, and savoring soufflés and chocolate mousse. Around March 22, Kahneman, who had turned 90 that month, also started emailing a personal message to several dozen of the people he was closest to. On March 26, Kahneman left his family and flew to Switzerland. His email explained why: My wife Alma Gottlieb is an anthropologist, and for years we had lived in small villages in West Africa, among the Beng people of Côte d’Ivoire. In 1993, during our third extended stay, news of my father’s death back in the U.S. arrived in the village, too late for us to return for his funeral. Stunned, I couldn’t decide what to do, how to mourn, until village elders offered to give my American father the ceremonies of a traditional Beng funeral. After days of elaborate ritual, the village’s religious leader, Kokora Kouassi, confided to us that my father now visited him in his dreams—from Wurugbé, the Beng afterlife—with messages of farewell and comfort. The Beng believe the dead exist in an invisible social world beside the living, and Kouassi’s dreams were meant to assure me that my father wasn’t far away at all. Instead, he hovered invisibly beside me.

My wife Alma Gottlieb is an anthropologist, and for years we had lived in small villages in West Africa, among the Beng people of Côte d’Ivoire. In 1993, during our third extended stay, news of my father’s death back in the U.S. arrived in the village, too late for us to return for his funeral. Stunned, I couldn’t decide what to do, how to mourn, until village elders offered to give my American father the ceremonies of a traditional Beng funeral. After days of elaborate ritual, the village’s religious leader, Kokora Kouassi, confided to us that my father now visited him in his dreams—from Wurugbé, the Beng afterlife—with messages of farewell and comfort. The Beng believe the dead exist in an invisible social world beside the living, and Kouassi’s dreams were meant to assure me that my father wasn’t far away at all. Instead, he hovered invisibly beside me. Can you pass me the whatchamacallit? It’s right over there next to the thingamajig.

Can you pass me the whatchamacallit? It’s right over there next to the thingamajig. T

T In January,

In January, Nobel Laureate and a psychologist, best known for his work on psychology of judgment and decision-making as well as behavioural economics,

Nobel Laureate and a psychologist, best known for his work on psychology of judgment and decision-making as well as behavioural economics,