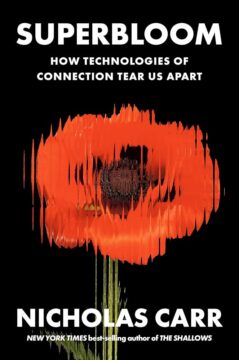

Nicholas Carr at After Babel:

Self-expression is good, we tell ourselves, and it’s good to hear what others have to say. The more we’re able to converse, to share our thoughts, opinions, and experiences, the better we’ll understand one another and the more harmonious society will become. If communication is good, more communication must be better.

Self-expression is good, we tell ourselves, and it’s good to hear what others have to say. The more we’re able to converse, to share our thoughts, opinions, and experiences, the better we’ll understand one another and the more harmonious society will become. If communication is good, more communication must be better.

But what if that’s wrong? What if communication, when its speed and volume are amped up too far, turns into a destructive force rather than a constructive one? What if too much communication breeds misunderstanding rather than understanding, mistrust rather than trust, strife rather than harmony?

Those uncomfortable questions lie at the heart of my new book, Superbloom: How Technologies of Connection Tear Us Apart. Drawing evidence from history, psychology, and sociology, I argue that our rush to use ever more powerful online media technologies to ratchet up the efficiency of communication has been reckless. Even as the unremitting flow of words and images seizes our attention, it overwhelms the sense-making and emotion-regulating capacities of the human nervous system.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

M

M Mary McLeod Bethune (1875-1955)

Mary McLeod Bethune (1875-1955) C

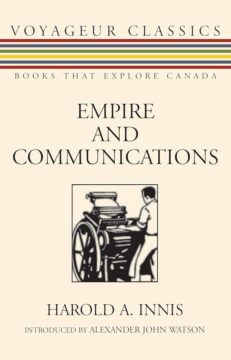

C With its emphasis on media’s formative role in a society’s development, “Minerva’s Owl” would come to be seen as a founding document — maybe the founding document — of the academic discipline of media studies that emerged in the second half of the twentieth century. In 1964, the celebrated media savant Marshall McLuhan, who like Innis was a professor at the University of Toronto, wrote that he saw his own recent book, The Gutenberg Galaxy, as “a footnote to the observations of Innis.” The distinguished American educator and media theorist James Carey called Innis’s work “the great achievement in communications on this continent.”

With its emphasis on media’s formative role in a society’s development, “Minerva’s Owl” would come to be seen as a founding document — maybe the founding document — of the academic discipline of media studies that emerged in the second half of the twentieth century. In 1964, the celebrated media savant Marshall McLuhan, who like Innis was a professor at the University of Toronto, wrote that he saw his own recent book, The Gutenberg Galaxy, as “a footnote to the observations of Innis.” The distinguished American educator and media theorist James Carey called Innis’s work “the great achievement in communications on this continent.” S

S

Eric Kaufmann: Obviously you in your book, The Identity Trap, give a pretty good account of one route, I think, towards this, which is sort of the whole idea of strategic essentialism that came out of left-wing intellectual thought. I know yourself and Francis Fukuyama and Chris Rufo and others have sketched out its development out of essentially the post-Marxist left. What I try to do in my book, The Third Awokening, is to look at the more liberal humanitarian, if you like, prong of this, which runs through psychotherapy and gets us towards a kind of humanitarian extremism. And so I put a lot of emphasis on this idea of cranking the dial of humanitarianism.

Eric Kaufmann: Obviously you in your book, The Identity Trap, give a pretty good account of one route, I think, towards this, which is sort of the whole idea of strategic essentialism that came out of left-wing intellectual thought. I know yourself and Francis Fukuyama and Chris Rufo and others have sketched out its development out of essentially the post-Marxist left. What I try to do in my book, The Third Awokening, is to look at the more liberal humanitarian, if you like, prong of this, which runs through psychotherapy and gets us towards a kind of humanitarian extremism. And so I put a lot of emphasis on this idea of cranking the dial of humanitarianism. Adrian Ward had been driving confidently around Austin, Texas, for nine years — until last November, when he started getting lost. Ward’s phone had been acting up, and Apple maps had stopped working. Suddenly, Ward couldn’t even find his way to the home of a good friend, making him realize how much he’d relied on the technology in the past. “I just instinctively put on the map and do what it says,” he says.

Adrian Ward had been driving confidently around Austin, Texas, for nine years — until last November, when he started getting lost. Ward’s phone had been acting up, and Apple maps had stopped working. Suddenly, Ward couldn’t even find his way to the home of a good friend, making him realize how much he’d relied on the technology in the past. “I just instinctively put on the map and do what it says,” he says. Cleaver was born into and lived in a segregated world and didn’t question it. Once segregation was made illegal*, he realizes the world he was in, writing “Prior to 1954, we lived in an atmosphere of novocain. Negroes found it necessary, in order to maintain whatever sanity they could, to remain somewhat aloft and detached from ‘the problem.’ We accepted indignities and the mechanics of the apparatus of oppression without reacting by sitting-in or holding mass demonstrations.” (Cleaver, 4-5) Most of the African American writers I have read either grew up before segregation ended or after.

Cleaver was born into and lived in a segregated world and didn’t question it. Once segregation was made illegal*, he realizes the world he was in, writing “Prior to 1954, we lived in an atmosphere of novocain. Negroes found it necessary, in order to maintain whatever sanity they could, to remain somewhat aloft and detached from ‘the problem.’ We accepted indignities and the mechanics of the apparatus of oppression without reacting by sitting-in or holding mass demonstrations.” (Cleaver, 4-5) Most of the African American writers I have read either grew up before segregation ended or after. When the French crime film

When the French crime film L

L F

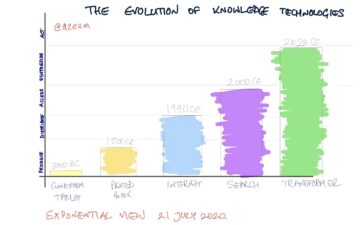

F A hint to the future arrived quietly over the weekend. For a long time, I’ve been discussing two parallel revolutions in AI: the rise of autonomous agents and the emergence of powerful Reasoners since OpenAI’s o1 was launched. These two threads have finally converged into something really impressive – AI systems that can conduct research with the depth and nuance of human experts, but at machine speed. OpenAI’s Deep Research demonstrates this convergence and gives us a sense of what the future might be. But to understand why this matters, we need to start with the building blocks: Reasoners and agents.

A hint to the future arrived quietly over the weekend. For a long time, I’ve been discussing two parallel revolutions in AI: the rise of autonomous agents and the emergence of powerful Reasoners since OpenAI’s o1 was launched. These two threads have finally converged into something really impressive – AI systems that can conduct research with the depth and nuance of human experts, but at machine speed. OpenAI’s Deep Research demonstrates this convergence and gives us a sense of what the future might be. But to understand why this matters, we need to start with the building blocks: Reasoners and agents.