Michael Prodger at The New Statesman:

In 1907, Ithell Colquhoun (pronounced “Eye-thell Co-hoon”), at the age of one, arrived in England with her family from India, where her father had been part of the colonial service. She would never go back to the country of her birth. A sense of this early dislocation from a mystical land nagged at her for the rest of her life, and was one of the motivations that drove her art and her writing for more than 60 years. She wrote of India that: “My origin was there, and there I would return, other than in dreams.” She declared herself with such certainty because she believed that a mesh of spiritual connections that transcended time and place lay beneath the physical world. There were, therefore, concealed knowledge and hidden realms ripe for discovery by adherents of the arcane arts.

Colquhoun’s early decades coincided with the “Occult Revival” of the late-19th and early-20th centuries, and she would prove to be a lifelong and exceptionally dedicated student, both as a painter and writer, and as a member of any number of spiritualist groups, from Druidry and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, to the Golden Section Order and the Fellowship of Isis.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

U.S. Steel mines iron ore in Minnesota and sends it across Lake Superior on freighters a thousand feet long. At Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, the ships enter the Soo Locks, which provide passage to the lower Great Lakes. Five hundred billion dollars’ worth of ore (and ninety-five per cent of the United States’ supply) annually moves through the locks, which have been managed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers since 1881. The Minnesota ships travel the long, dangling length of Lake Michigan and dock at its southern tip: Gary, Indiana.

U.S. Steel mines iron ore in Minnesota and sends it across Lake Superior on freighters a thousand feet long. At Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, the ships enter the Soo Locks, which provide passage to the lower Great Lakes. Five hundred billion dollars’ worth of ore (and ninety-five per cent of the United States’ supply) annually moves through the locks, which have been managed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers since 1881. The Minnesota ships travel the long, dangling length of Lake Michigan and dock at its southern tip: Gary, Indiana. O

O Shocking if not surprising investigations from the

Shocking if not surprising investigations from the  Sexual partners transfer their distinctive genital microbiome to each other during intercourse, a finding that could have implications for forensic investigations of sexual assault.

Sexual partners transfer their distinctive genital microbiome to each other during intercourse, a finding that could have implications for forensic investigations of sexual assault. The year 2014 was a heady moment in the economic policy world. That spring, French economist Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century was published in English to astounding commercial and intellectual

The year 2014 was a heady moment in the economic policy world. That spring, French economist Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century was published in English to astounding commercial and intellectual

“The freedom to write”: PEN America’s

“The freedom to write”: PEN America’s  Questions concerning the differences between Schelling’s and Hegel’s philosophical systems have always been of intense interest. This has been the case since Hegel decisively ended their friendship and collaboration by critically describing the early Schelling’s concept of the Absolute (the identity of identity and non-identity, or A=A [Dews, 75–76]) as the night “in which all cows are black” in the Phenomenology of Spirit in 1807 (Hegel 1977, 9, cf. Dews 75). Schelling’s Absolute, on Hegel’s account, was an abyss of darkness within which the dynamic development of real difference did not emerge. In contrast, Hegel thought his own dialectical system could lift difference out of the night, capturing the “reality of the finite” and the dynamic process of becoming (77). While Schelling quickly moved on from the “Identity System” in question, Hegel nevertheless remained an inescapable shadow haunting Schelling’s philosophical career.

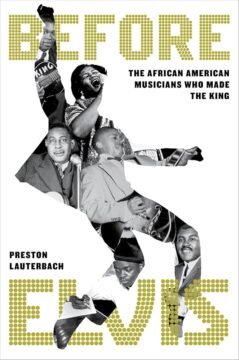

Questions concerning the differences between Schelling’s and Hegel’s philosophical systems have always been of intense interest. This has been the case since Hegel decisively ended their friendship and collaboration by critically describing the early Schelling’s concept of the Absolute (the identity of identity and non-identity, or A=A [Dews, 75–76]) as the night “in which all cows are black” in the Phenomenology of Spirit in 1807 (Hegel 1977, 9, cf. Dews 75). Schelling’s Absolute, on Hegel’s account, was an abyss of darkness within which the dynamic development of real difference did not emerge. In contrast, Hegel thought his own dialectical system could lift difference out of the night, capturing the “reality of the finite” and the dynamic process of becoming (77). While Schelling quickly moved on from the “Identity System” in question, Hegel nevertheless remained an inescapable shadow haunting Schelling’s philosophical career. The further we get from Elvis Presley’s death, the more a crude music industry frame takes hold: the blinding flash of his Sun Records youth, the snowballing Hollywood banality, and the celebrity pill junkie slumped on his toilet, dead at 42. Praise Allah for recent documentaries like Elvis Presley: The Searcher (Thom Zimny, 2018), and the Reinventing Elvis: The ’68 Comeback (John Scheinfeld, 2023), where the performer’s radical charisma speaks for itself. In the same way that historic recreations always comment on their contemporary context, the Elvis Presley of Sun Studios and early RCA singles between 1954 and 1958 will always sound tantalizingly out of reach to 21st-century ears—another 80 years of laissez-faire racism will do that.

The further we get from Elvis Presley’s death, the more a crude music industry frame takes hold: the blinding flash of his Sun Records youth, the snowballing Hollywood banality, and the celebrity pill junkie slumped on his toilet, dead at 42. Praise Allah for recent documentaries like Elvis Presley: The Searcher (Thom Zimny, 2018), and the Reinventing Elvis: The ’68 Comeback (John Scheinfeld, 2023), where the performer’s radical charisma speaks for itself. In the same way that historic recreations always comment on their contemporary context, the Elvis Presley of Sun Studios and early RCA singles between 1954 and 1958 will always sound tantalizingly out of reach to 21st-century ears—another 80 years of laissez-faire racism will do that. The advent of advanced AI systems capable of generating academic text — including “chain-of-thought” large language models with test-time web access — is poised to significantly influence scholarly writing and publishing. This review discusses how academia, particularly in quantitative social science, should adjust over the next decade to AI-assisted or AI-written articles. We summarize the current capabilities of AI in academic writing (from drafting and citation support to idea generation), highlight emerging trends, and weigh advantages against risks such as misinformation, plagiarism, and ethical dilemmas. We then offer speculative predictions for the coming ten years, grounded in literature and present data on AI’s impact to date. An empirical analysis compiles real-world data illustrating AI’s growing footprint in research output. Finally, we provide policy and workflow recommendations for journals, peer reviewers, editors, and scholars, presented in an exhaustive table. Our aim is to inform a balanced approach to harnessing AI’s benefits in academic writing while safeguarding integrity

The advent of advanced AI systems capable of generating academic text — including “chain-of-thought” large language models with test-time web access — is poised to significantly influence scholarly writing and publishing. This review discusses how academia, particularly in quantitative social science, should adjust over the next decade to AI-assisted or AI-written articles. We summarize the current capabilities of AI in academic writing (from drafting and citation support to idea generation), highlight emerging trends, and weigh advantages against risks such as misinformation, plagiarism, and ethical dilemmas. We then offer speculative predictions for the coming ten years, grounded in literature and present data on AI’s impact to date. An empirical analysis compiles real-world data illustrating AI’s growing footprint in research output. Finally, we provide policy and workflow recommendations for journals, peer reviewers, editors, and scholars, presented in an exhaustive table. Our aim is to inform a balanced approach to harnessing AI’s benefits in academic writing while safeguarding integrity