by Anders Wallace

On Monday, April 23rd, a 25-year old man named Alek Minassian drove a rented van down a sidewalk in Toronto, killing eight women and two men. The attack was reminiscent of recent Islamist terror attacks in New York, London, Stockholm, Nice, and Berlin. Just before his massacre, he posted a note on Facebook announcing: “Private (Recruit) Minassian Infantry 00010, wishing to speak to Sgt 4chan please. C23249161, the Incel Rebellion has already begun! We will overthrow all the Chads and Stacys! All hail the Supreme Gentleman Elliot Rodger!” The phrase paid homage to a young man named Elliot Rodger. In 2014, Rodger shot and killed six people in Isla Vista, California, before taking his own life.

On Monday, April 23rd, a 25-year old man named Alek Minassian drove a rented van down a sidewalk in Toronto, killing eight women and two men. The attack was reminiscent of recent Islamist terror attacks in New York, London, Stockholm, Nice, and Berlin. Just before his massacre, he posted a note on Facebook announcing: “Private (Recruit) Minassian Infantry 00010, wishing to speak to Sgt 4chan please. C23249161, the Incel Rebellion has already begun! We will overthrow all the Chads and Stacys! All hail the Supreme Gentleman Elliot Rodger!” The phrase paid homage to a young man named Elliot Rodger. In 2014, Rodger shot and killed six people in Isla Vista, California, before taking his own life.

Minassian and Rodger were members of an online subculture called “incels.” Like a 21st Century American psycho Norman Bates, they killed women because they felt sexually rejected by them. Incels are a particularly vicious subculture of the manosphere. The manosphere is a digital ecosystem of blogs, podcasts, online forums, and hidden groups on sites like Facebook and Tumblr. Here you’ll find a motley crew of men’s rights activists, white supremacists, conspiracy theorists, angry divorcees, disgruntled dads, male victims of abuse, self-improvement junkies, bodybuilders, bored gamers, alt-righters, pickup artists, and alienated teenagers. What they share is a vicious response to feminists (often dubbed “feminazis”) and so-called “social justice warriors.” They blame their anger on identity politics, affirmative action, and the neoliberal state, which they perceive are compromising equality and oppressing their own free speech. Their heated resentment warps postmodern (post-1960s) countercultural beliefs currently in vogue among alt-right provocateurs like Milo Yiannopoulos and Alex Jones: specifically, that Americans need to liberate their consciousness from lies and falsehoods borne out by corporate manipulation, government conspiracies, and politically-correct social norms.

Very few people would become so inflamed by the perception of sexual rejection that they would wantonly kill strangers. But sexual abuse, rape, and other types of gendered coercion are rampant in U.S. society. The recent #MeToo movement has shown a spotlight on these men, though mostly only the very rich and successful ones. Behind computers and in bedrooms across the nation, hundreds of thousands of men nurse a seething sense of anger, shame, and resentment coupled with entitlement and stifled desire. Some of these men choose not to kill or rape (though they may, from the privacy of their skulls, want to do both those things). These men are trying to fix their dating lives through masculine kinds of self-help. These are men’s pickup, dating, and seduction communities. Read more »

Nothing, however, prepares one for the tender ferocity of Bacon’s isolated, entrapped figures. In the earliest of these, the large canvas of Figure in a Landscape(1945), a curled-up, almost human form appears to be submerged in a desert—we see his arm and part of his body, but the legs of his suit hang, empty, over a bench. This is masculinity destroyed. The sense of desperation is even stronger in Bacon’s paintings of animals, such as Dog (1952), in which the dog whirls like a dervish, absorbed in chasing its tail, while cars speed by on a palm-bordered freeway, or Study of a Baboon (1953), where the monkey flies and howls against the mesh of a fence. In their struggles, these animals are the fellows of Bacon’s “screaming popes”: in Study after Velazquez (1950), a businessman in a dark suit, jaws wrenched open in a silent yell, is trapped behind red bars that fall like a curtain of blood. The curators connect Bacon’s postwar angst with Giacometti’s elongated statues, isolated in space, and to the philosophy of existentialism. Yet Bacon’s vehement brushstrokes speak of energy and involvement, physical, not cerebral responses. In Study for Portrait II (after the Life Mask of William Blake) (1955), you feel the urgent vision behind the lidded eyes. He cares, passionately.

Nothing, however, prepares one for the tender ferocity of Bacon’s isolated, entrapped figures. In the earliest of these, the large canvas of Figure in a Landscape(1945), a curled-up, almost human form appears to be submerged in a desert—we see his arm and part of his body, but the legs of his suit hang, empty, over a bench. This is masculinity destroyed. The sense of desperation is even stronger in Bacon’s paintings of animals, such as Dog (1952), in which the dog whirls like a dervish, absorbed in chasing its tail, while cars speed by on a palm-bordered freeway, or Study of a Baboon (1953), where the monkey flies and howls against the mesh of a fence. In their struggles, these animals are the fellows of Bacon’s “screaming popes”: in Study after Velazquez (1950), a businessman in a dark suit, jaws wrenched open in a silent yell, is trapped behind red bars that fall like a curtain of blood. The curators connect Bacon’s postwar angst with Giacometti’s elongated statues, isolated in space, and to the philosophy of existentialism. Yet Bacon’s vehement brushstrokes speak of energy and involvement, physical, not cerebral responses. In Study for Portrait II (after the Life Mask of William Blake) (1955), you feel the urgent vision behind the lidded eyes. He cares, passionately.

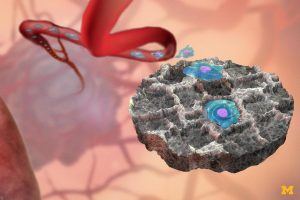

A small device implanted under the skin shows promise for improving breast cancer survival by catching cancer cells and slowing the development of metastatic tumors in other organs. These findings, based on experiments in mice and reported in the journal Cancer Research, suggest a path for identifying metastatic cancer early and intervening to improve outcomes. “This study shows that in the metastatic setting, early detection combined with a therapeutic intervention can improve outcomes. Early detection of a primary tumor is generally associated with improved outcomes. But that’s not necessarily been tested in metastatic cancer,” says study author Lonnie D. Shea, Ph.D., the William and Valerie Hall Department Chair of Biomedical Engineering at the University of Michigan.

A small device implanted under the skin shows promise for improving breast cancer survival by catching cancer cells and slowing the development of metastatic tumors in other organs. These findings, based on experiments in mice and reported in the journal Cancer Research, suggest a path for identifying metastatic cancer early and intervening to improve outcomes. “This study shows that in the metastatic setting, early detection combined with a therapeutic intervention can improve outcomes. Early detection of a primary tumor is generally associated with improved outcomes. But that’s not necessarily been tested in metastatic cancer,” says study author Lonnie D. Shea, Ph.D., the William and Valerie Hall Department Chair of Biomedical Engineering at the University of Michigan.

It’s with a certain pleasure that I can recall the exact moment I was seduced by the musical avant-garde. It was in the fourth grade, in a public elementary school somewhere in New Jersey. Our music teacher, Mrs. Jones, would visit the classroom several times a week, accompanied by an ancient record player and a stack of LPs. You could always tell when she was coming down the hall because the wheels of the cart had a particularly squeak-squeak-wheeze pattern. However, such a Cageian sensibility was not the occasion of my epiphany. I’m also not sure if fourth-graders are allowed to have epiphanies, or, which is likelier, if they are not having them on a daily basis.

It’s with a certain pleasure that I can recall the exact moment I was seduced by the musical avant-garde. It was in the fourth grade, in a public elementary school somewhere in New Jersey. Our music teacher, Mrs. Jones, would visit the classroom several times a week, accompanied by an ancient record player and a stack of LPs. You could always tell when she was coming down the hall because the wheels of the cart had a particularly squeak-squeak-wheeze pattern. However, such a Cageian sensibility was not the occasion of my epiphany. I’m also not sure if fourth-graders are allowed to have epiphanies, or, which is likelier, if they are not having them on a daily basis.

If by “objectivity” we mean “wholly lacking personal biases”, in wine tasting, this idea can be ruled out. There are too many individual differences among wine tasters, regardless of how much expertise they have acquired, to aspire to this kind of objectivity. But traditional aesthetics has employed a related concept which does seem attainable—an attitude of disinterestedness, which provides much of what we want from objectivity. We can’t eliminate differences among tasters that arise from biology or life history, but we can minimize the influence of personal motives and desires that might distort the tasting experience.

If by “objectivity” we mean “wholly lacking personal biases”, in wine tasting, this idea can be ruled out. There are too many individual differences among wine tasters, regardless of how much expertise they have acquired, to aspire to this kind of objectivity. But traditional aesthetics has employed a related concept which does seem attainable—an attitude of disinterestedness, which provides much of what we want from objectivity. We can’t eliminate differences among tasters that arise from biology or life history, but we can minimize the influence of personal motives and desires that might distort the tasting experience.

This last month or so I’ve been desperately trying to get the 2000s chapter fit for human consumption. I’ve

This last month or so I’ve been desperately trying to get the 2000s chapter fit for human consumption. I’ve

The fact that anything happens securely on the web should be mind-boggling. In some ways, the internet is like a group of people shouting at each other across an open field. How can you hold a secret conversation when anyone might be listening? How do you prevent imposters, when you can’t always see the face behind the shout?

The fact that anything happens securely on the web should be mind-boggling. In some ways, the internet is like a group of people shouting at each other across an open field. How can you hold a secret conversation when anyone might be listening? How do you prevent imposters, when you can’t always see the face behind the shout? On Monday, April 23rd, a 25-year old man named Alek Minassian drove a rented van down a sidewalk in Toronto, killing eight women and two men. The attack was reminiscent of recent Islamist terror attacks in New York, London, Stockholm, Nice, and Berlin. Just before his massacre, he posted a note on Facebook announcing: “Private (Recruit) Minassian Infantry 00010, wishing to speak to Sgt 4chan please. C23249161, the Incel Rebellion has already begun! We will overthrow all the Chads and Stacys! All hail the Supreme Gentleman Elliot Rodger!” The phrase paid homage to a young man named Elliot Rodger. In 2014, Rodger shot and killed six people in Isla Vista, California, before taking his own life.

On Monday, April 23rd, a 25-year old man named Alek Minassian drove a rented van down a sidewalk in Toronto, killing eight women and two men. The attack was reminiscent of recent Islamist terror attacks in New York, London, Stockholm, Nice, and Berlin. Just before his massacre, he posted a note on Facebook announcing: “Private (Recruit) Minassian Infantry 00010, wishing to speak to Sgt 4chan please. C23249161, the Incel Rebellion has already begun! We will overthrow all the Chads and Stacys! All hail the Supreme Gentleman Elliot Rodger!” The phrase paid homage to a young man named Elliot Rodger. In 2014, Rodger shot and killed six people in Isla Vista, California, before taking his own life. Between 2001 and 2015, sales of translated fiction grew by 96%. One reason, argues Daniel Hahn, who last year

Between 2001 and 2015, sales of translated fiction grew by 96%. One reason, argues Daniel Hahn, who last year  Three years ago

Three years ago Chimpanzees are among human beings’

Chimpanzees are among human beings’  The day after a

The day after a  Skye Cleary and Massimo Pigliucci in Aeon:

Skye Cleary and Massimo Pigliucci in Aeon: