by Christopher Bacas

by Christopher Bacas

We make unplanned pilgrimages; a friend, job or tragedy send us barefoot around sacred mountains. Eyes fixed on the path, we’re prevented from losing our way by loyalty, diligence or grief. Anyone we pass is possibly the most important person we will ever (not) meet.

A job: play half-hour concerts; moving from unit to unit in an eleven-story Upper West Side building. Our private audiences, home-bound seniors. We are a saxophone/bass duo. My partner, Joshua, sings in English and Spanish. Our employers provide a list with names, apartment numbers and an emergency contact.

On the ninth floor, our first stop, a caretaker slowly opens the door. A vector of heat escapes around her into the drafty hall.

“Musica?”

“Si, si”

We announce our sponsor’s name. She doesn’t recognize it. Voices inside call out, ricocheting off a bare floor. She opens the door all the way. In the center of the room, behind a walker, Nayeli slumps into a kitchen chair. Swollen with disuse, her feet rest on a fresh, spread out Depends. In the corner, her husband, Tolentino, in a jacket and spiffy sneakers, sits on the edge of a plush armchair, knees tight. He gets up to shake my hand. Then, I lean in to shake his wife’s.

I pull my horn out of the case, assemble it and get ready to play. With upturned eyes, the couple appraise our instruments as if they were caged snakes. A brief cloudburst follows; small sounds musicians make before playing: soft descending notes in whooshing funnels, rattles and clicks. Then, silence, awkward and centripetal, whirling us into the present. We look at them. Read more »

In 1964, when Joseph Brodsky was 24, he was brought to trial for “social parasitism.” In the view of the state, the young poet was a freeloader. His employment history was spotty at best: he was out of work for six months after losing his first factory job, and then for another four months after returning from a geological expedition. (Being a writer didn’t count as a job, and certainly not if you’d hardly published anything.) In response to the charge, Brodsky leveled a straightforward defense: he’d been thinking about stuff, and writing. But there was a new order to build, and if you weren’t actively contributing to society you were screwing it up.

In 1964, when Joseph Brodsky was 24, he was brought to trial for “social parasitism.” In the view of the state, the young poet was a freeloader. His employment history was spotty at best: he was out of work for six months after losing his first factory job, and then for another four months after returning from a geological expedition. (Being a writer didn’t count as a job, and certainly not if you’d hardly published anything.) In response to the charge, Brodsky leveled a straightforward defense: he’d been thinking about stuff, and writing. But there was a new order to build, and if you weren’t actively contributing to society you were screwing it up. The older you get the more difficult it is to learn to speak French like a Parisian. But no one knows exactly what the cutoff point is—at what age it becomes harder, for instance, to pick up noun-verb agreements in a new language. In one of the largest linguistics studies ever conducted—a viral internet survey that drew two thirds of a million respondents—researchers from three Boston-based universities showed children are proficient at learning a second language up until the age of 18, roughly 10 years later than earlier estimates. But the study also showed that it is best to start by age 10 if you want to achieve the grammatical fluency of a native speaker.

The older you get the more difficult it is to learn to speak French like a Parisian. But no one knows exactly what the cutoff point is—at what age it becomes harder, for instance, to pick up noun-verb agreements in a new language. In one of the largest linguistics studies ever conducted—a viral internet survey that drew two thirds of a million respondents—researchers from three Boston-based universities showed children are proficient at learning a second language up until the age of 18, roughly 10 years later than earlier estimates. But the study also showed that it is best to start by age 10 if you want to achieve the grammatical fluency of a native speaker. I think I know what it feels like to be “red-pilled,” the alt-right’s preferred metaphor for losing one’s faith in received assumptions and turning toward ideas that once seemed dangerous.

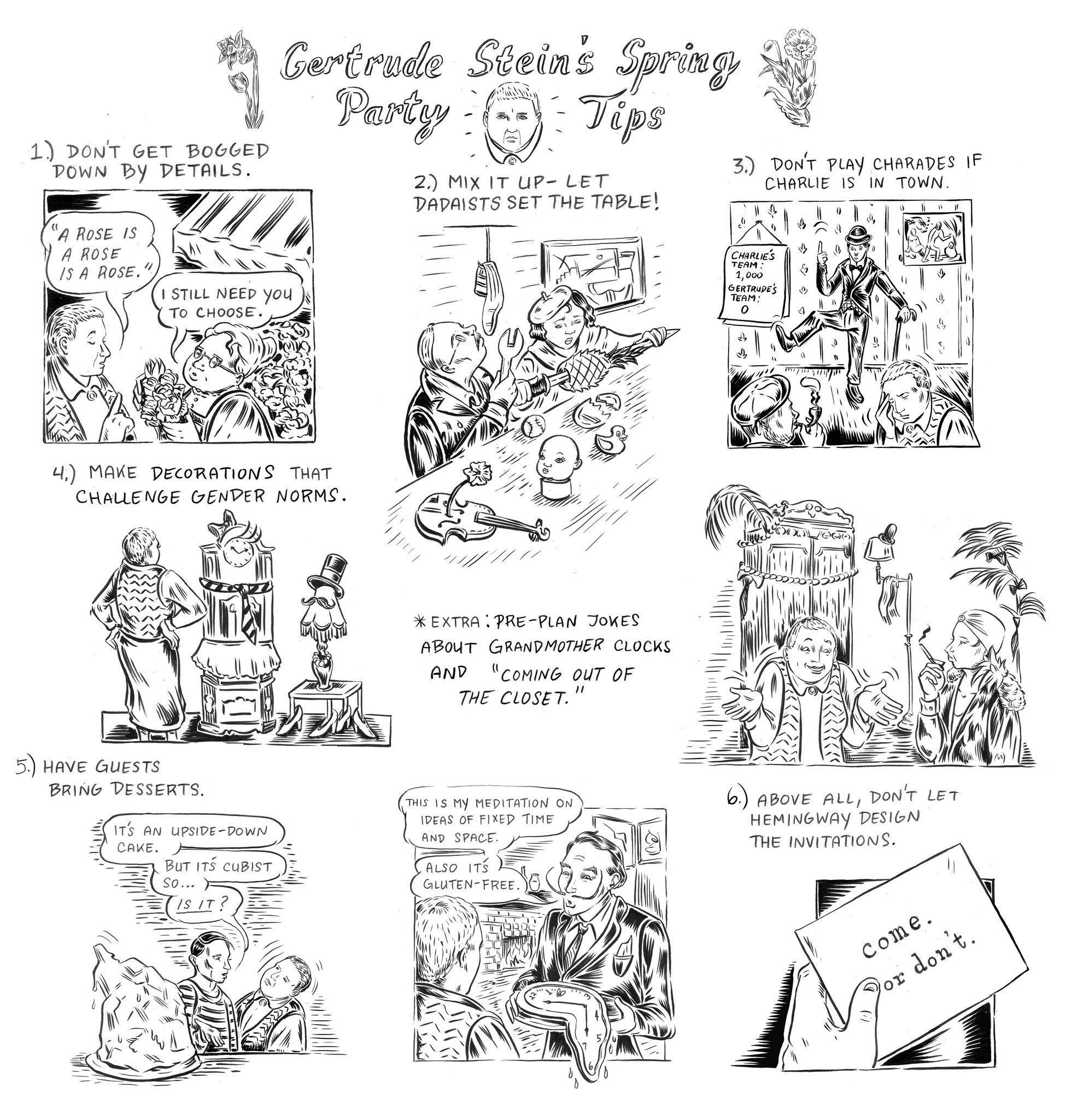

I think I know what it feels like to be “red-pilled,” the alt-right’s preferred metaphor for losing one’s faith in received assumptions and turning toward ideas that once seemed dangerous. The Writer exists in two worlds: the world he’s creating and the world in which he wears the same shirt a lot. The Writer successfully holds each world responsible for his failings in the other, a Ping-Ponging of accountability that frees him to wake up around elevenish.

The Writer exists in two worlds: the world he’s creating and the world in which he wears the same shirt a lot. The Writer successfully holds each world responsible for his failings in the other, a Ping-Ponging of accountability that frees him to wake up around elevenish. This is a time of much division. Families and communities are splintered by polarizing narratives. Outrage surrounds geopolitical discourse—so much so that anxiety often becomes a sort of white noise, making it increasingly difficult to trigger intense, acute anger. The effect can be desensitizing, like driving 60 miles per hour and losing hold of the reality that a minor error could result in instant death.

This is a time of much division. Families and communities are splintered by polarizing narratives. Outrage surrounds geopolitical discourse—so much so that anxiety often becomes a sort of white noise, making it increasingly difficult to trigger intense, acute anger. The effect can be desensitizing, like driving 60 miles per hour and losing hold of the reality that a minor error could result in instant death. When Muhammad bin Salman, Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince, visited New York earlier this year, the face of Ahmed Mater, the kingdom’s most celebrated artist, was beamed onto an enormous billboard in Times Square. In recent years, he has been feted at exhibitions in London, New York and Venice. He dominates the Saudi art scene so thoroughly that his peers struggle for attention. “He’s the only artist anyone writes about,” says one Saudi curator. In 2017 Mater was appointed as artistic director of the Prince’s cultural and educational foundation, entrusted to promote art across the kingdom and liberalise the school system. He plays a crucial role in the enormously ambitious plan for economic and social transformation, which aims to wean the country off reliance on oil revenues, strip down the power of clerics and dispel a reputation for medieval obscurantism and misogyny.

When Muhammad bin Salman, Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince, visited New York earlier this year, the face of Ahmed Mater, the kingdom’s most celebrated artist, was beamed onto an enormous billboard in Times Square. In recent years, he has been feted at exhibitions in London, New York and Venice. He dominates the Saudi art scene so thoroughly that his peers struggle for attention. “He’s the only artist anyone writes about,” says one Saudi curator. In 2017 Mater was appointed as artistic director of the Prince’s cultural and educational foundation, entrusted to promote art across the kingdom and liberalise the school system. He plays a crucial role in the enormously ambitious plan for economic and social transformation, which aims to wean the country off reliance on oil revenues, strip down the power of clerics and dispel a reputation for medieval obscurantism and misogyny. I lost my heart from the moment I first saw it. Cill Rialaig is about as far west as you can go in Europe without falling off the edge. A magical place set in a wild landscape full of ghosts and memories, it’s a pre-famine village that clings to a steep slope, 300ft above the sea in Kerry, on the west coast of Ireland.

I lost my heart from the moment I first saw it. Cill Rialaig is about as far west as you can go in Europe without falling off the edge. A magical place set in a wild landscape full of ghosts and memories, it’s a pre-famine village that clings to a steep slope, 300ft above the sea in Kerry, on the west coast of Ireland. Scientists are preparing to create “miniature brains” that have been genetically engineered to contain Neanderthal DNA, in an unprecedented attempt to understand how humans differ from our closest relatives.

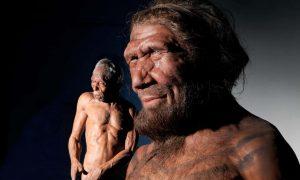

Scientists are preparing to create “miniature brains” that have been genetically engineered to contain Neanderthal DNA, in an unprecedented attempt to understand how humans differ from our closest relatives. It began inconspicuously, as so many riots do. People jostled in a sparsely policed public square lined with Jewish-owned shops. Worshippers idled after Easter services at the nearby Ciuflea Church, some drinking steadily once services ended, and teenagers as well as Jews—restless near the end of the long, eight-day Passover festival—were all rubbing shoulders. The weather was suddenly and blissfully temperate, dry after intermittent rain.

It began inconspicuously, as so many riots do. People jostled in a sparsely policed public square lined with Jewish-owned shops. Worshippers idled after Easter services at the nearby Ciuflea Church, some drinking steadily once services ended, and teenagers as well as Jews—restless near the end of the long, eight-day Passover festival—were all rubbing shoulders. The weather was suddenly and blissfully temperate, dry after intermittent rain. More

More  As a kid, I’d sometimes try to imagine what life would be like without a particular sense or part of my body, like with questions from the Would You Rather? game. Would you rather be deaf or blind? Would you rather have no legs or no arms? I’d try to erase the sound of my mom’s piano playing, the sight of the ground growing smaller as I soared on the tree swing in my backyard, or the feeling of playing basketball so hard my lungs might explode, but I just couldn’t. How could life go on without these sensations that were so tied to my idea of what it meant to be alive? I guess I’ve been feeling extra contemplative and nostalgic these days because I recently went through a pretty significant break-up…with my smartphone. My relationship with my phone was unhealthy in a lot of ways. I don’t remember exactly when I started needing to hold it during dinner or having to check Twitter before I got out of bed in the morning, but at some point I’d decided I couldn’t be without it. I’d started to notice just how often I was on my phone—and how unpleasant much of that time had become—when my daughter came along, and, just like that, time became infinitely more precious. So, I said goodbye. Now, as I reflect on the almost seven years my smartphone and I spent together, I’m starting to realize: What I had with my phone was largely physical.

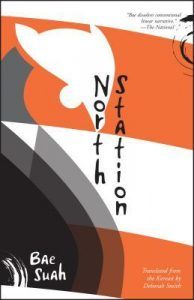

As a kid, I’d sometimes try to imagine what life would be like without a particular sense or part of my body, like with questions from the Would You Rather? game. Would you rather be deaf or blind? Would you rather have no legs or no arms? I’d try to erase the sound of my mom’s piano playing, the sight of the ground growing smaller as I soared on the tree swing in my backyard, or the feeling of playing basketball so hard my lungs might explode, but I just couldn’t. How could life go on without these sensations that were so tied to my idea of what it meant to be alive? I guess I’ve been feeling extra contemplative and nostalgic these days because I recently went through a pretty significant break-up…with my smartphone. My relationship with my phone was unhealthy in a lot of ways. I don’t remember exactly when I started needing to hold it during dinner or having to check Twitter before I got out of bed in the morning, but at some point I’d decided I couldn’t be without it. I’d started to notice just how often I was on my phone—and how unpleasant much of that time had become—when my daughter came along, and, just like that, time became infinitely more precious. So, I said goodbye. Now, as I reflect on the almost seven years my smartphone and I spent together, I’m starting to realize: What I had with my phone was largely physical. Bae Suah seems to know that writing is a kind of time travel, and in each of these stories, brought deftly into English by Deborah Smith, the caroming and hyperlinking movements that characterize this traveling raise such questions as: what does it demand of me when I reach out to you? Where does my memory of you end and your reality begin? Why do I remember only that which I remember? And, as I write all of this, do I move any closer toward the answers?

Bae Suah seems to know that writing is a kind of time travel, and in each of these stories, brought deftly into English by Deborah Smith, the caroming and hyperlinking movements that characterize this traveling raise such questions as: what does it demand of me when I reach out to you? Where does my memory of you end and your reality begin? Why do I remember only that which I remember? And, as I write all of this, do I move any closer toward the answers? W

W