Stan Carey in Sentence First:

Like has undergone radical developments in modern English. It can function as a hedge (‘I’ll be there in like an hour’), a discourse particle (‘This like serves a pragmatic function’), and a sentence adverb (‘It’s common in Ireland, like’). These and other non-standard usages are frequently criticised, but they’re probably older than critics think.

Like has undergone radical developments in modern English. It can function as a hedge (‘I’ll be there in like an hour’), a discourse particle (‘This like serves a pragmatic function’), and a sentence adverb (‘It’s common in Ireland, like’). These and other non-standard usages are frequently criticised, but they’re probably older than critics think.

More recent is the so-called quotative like (‘I’m like, Whoa!’), also often disparaged. This became widely established impressively fast and is leading to some remarkable usages in younger generations: children saying things like ‘What’s Ernie like?’ to mean ‘What’s Ernie saying?’

So some uses of like are emerging right now, spreading through younger speech communities. In episode 278 of Australia’s Talk the Talk podcast, guest Alexandra D’Arcy – a linguistics professor who literally wrote the book on like – says that while she might say ‘at like the same time’, her son can say ‘at the like same time’, which is not in her grammar at all. It’s a subtle but striking difference.

It gets better. The latest novel use to which like is being put is as an infix. Infixes are a pretty small set in English, so a new one is a genuine surprise, linguistically. In some ways it is unlikeprecedented.

More here.

IQ scores have been steadily falling for the past few decades, and environmental factors are to blame, a new study says.

IQ scores have been steadily falling for the past few decades, and environmental factors are to blame, a new study says. If you wade through the

If you wade through the  What do we mean by diversity? And why is it good – or not?

What do we mean by diversity? And why is it good – or not? I first encountered Lorrie Moore when I read “How to Become a Writer,” a mesmerizingly bleak story from her 1985 debut collection, Self-Help, which I imagine to be so frequently anthologized because editors want something of hers and because the title is so appealing. Besides, it’s a promising one, suggesting a clear set of instructions. Like much of Self-Help, the story is voiced in second-person imperative, but it can only offer directions down a road to nowhere: “First,” its opening lines instruct, “try to be something, anything, else.”

I first encountered Lorrie Moore when I read “How to Become a Writer,” a mesmerizingly bleak story from her 1985 debut collection, Self-Help, which I imagine to be so frequently anthologized because editors want something of hers and because the title is so appealing. Besides, it’s a promising one, suggesting a clear set of instructions. Like much of Self-Help, the story is voiced in second-person imperative, but it can only offer directions down a road to nowhere: “First,” its opening lines instruct, “try to be something, anything, else.” After the success of my predictions for the 2010 and

After the success of my predictions for the 2010 and  One way to gauge likely outcomes is to look at bookmakers’ odds. These companies use professional statisticians to analyze extensive databases of results in a way that quantifies the probability of different outcomes of any possible match. In this way, bookmakers can offer odds on all the games that will kick off in the next few weeks, as well as odds on potential winners.

One way to gauge likely outcomes is to look at bookmakers’ odds. These companies use professional statisticians to analyze extensive databases of results in a way that quantifies the probability of different outcomes of any possible match. In this way, bookmakers can offer odds on all the games that will kick off in the next few weeks, as well as odds on potential winners. Into the shifting sands of Oman he follows the stories of

Into the shifting sands of Oman he follows the stories of  ‘Is Finnegans Wake really important?’ my student asked me a few years ago. He was from India, sent to Australia for his education at great expense by his parents. I felt sorry for him so I had invented some cash-in-hand filing work, much of which involved compiling notes, essays, articles, emails and letters in relation to Finnegans Wake. Now he was daring to ask whether the book I’d spent much of my adult life devoted to was really of any importance.

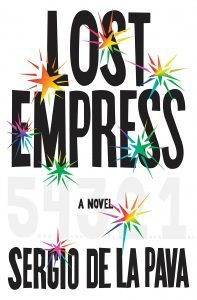

‘Is Finnegans Wake really important?’ my student asked me a few years ago. He was from India, sent to Australia for his education at great expense by his parents. I felt sorry for him so I had invented some cash-in-hand filing work, much of which involved compiling notes, essays, articles, emails and letters in relation to Finnegans Wake. Now he was daring to ask whether the book I’d spent much of my adult life devoted to was really of any importance. One of the most ambitious, audacious books of recent memory, Lost Empress by Sergio de la Pava brings together a smorgasbord of plot lines and scenes ranging from the serious to the comic, including: a clash between the NFL and the Indoor Football League, the history of Joni Mitchell’s career, the heist of a lost Dalí, a court case involving a high-profile murder and an incredibly intelligent inmate, the Mandela Effect, the life of a 911 operator, the origins of a brain tumor, quantum mechanics and the mind-body divide as it relates to time and consciousness, an accidental impaling and the said consequences of such as relates to the nature of getting revenge, multiple love stories that go unfulfilled, and a fight between a pig mascot and a crab one.

One of the most ambitious, audacious books of recent memory, Lost Empress by Sergio de la Pava brings together a smorgasbord of plot lines and scenes ranging from the serious to the comic, including: a clash between the NFL and the Indoor Football League, the history of Joni Mitchell’s career, the heist of a lost Dalí, a court case involving a high-profile murder and an incredibly intelligent inmate, the Mandela Effect, the life of a 911 operator, the origins of a brain tumor, quantum mechanics and the mind-body divide as it relates to time and consciousness, an accidental impaling and the said consequences of such as relates to the nature of getting revenge, multiple love stories that go unfulfilled, and a fight between a pig mascot and a crab one. On my way to a meeting on cancer and personalized medicine a few weeks ago, I found myself thinking, improbably, of the Saul Steinberg New Yorker cover illustration “View From Ninth Avenue.” Steinberg’s drawing (yes, you’ve seen it — in undergraduate dorm rooms, in subway ads) depicts a mental map of the world viewed through the eyes of a typical New Yorker. We’re somewhere on Ninth Avenue, looking out toward the water. Tenth Avenue looms large, thrumming with pedestrians and traffic. The Hudson is a band of gray-blue. But the rest of the world is gone — irrelevant, inconsequential, specks of sesame falling off a bagel. Kansas City, Chicago, Las Vegas and Los Angeles are blips on the horizon. There’s a strip of water denoting the Pacific Ocean, and faraway blobs of rising land: Japan, China, Russia. The whole thing is a wry joke on self-obsession and navel gazing: A New Yorker’s world begins and ends in New York.

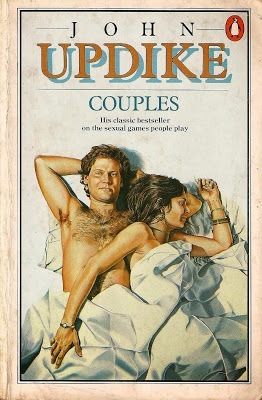

On my way to a meeting on cancer and personalized medicine a few weeks ago, I found myself thinking, improbably, of the Saul Steinberg New Yorker cover illustration “View From Ninth Avenue.” Steinberg’s drawing (yes, you’ve seen it — in undergraduate dorm rooms, in subway ads) depicts a mental map of the world viewed through the eyes of a typical New Yorker. We’re somewhere on Ninth Avenue, looking out toward the water. Tenth Avenue looms large, thrumming with pedestrians and traffic. The Hudson is a band of gray-blue. But the rest of the world is gone — irrelevant, inconsequential, specks of sesame falling off a bagel. Kansas City, Chicago, Las Vegas and Los Angeles are blips on the horizon. There’s a strip of water denoting the Pacific Ocean, and faraway blobs of rising land: Japan, China, Russia. The whole thing is a wry joke on self-obsession and navel gazing: A New Yorker’s world begins and ends in New York. By the time Couples came out, John Updike had already published four novels, three story collections, two poetry collections, and a volume of assorted prose. He had been called, by the New York Times Book Review, “the most significant young novelist in America,” and had been sent by the State Department on a tour of the Communist bloc. And yet there was a growing sense that he had not made a major statement on the issues of the day. He could describe a barn well enough, but to what end? The man whose name will be forever asterisked with the insult David Foster Wallace made famous—“just a penis with a thesaurus”—was thought to be clever but a little small, too decorative, and overly fond of childhood reminiscence. Norman Podhoretz complained that Updike “has very little to say.” John Aldridge put him in “the second or just possibly the third rank of serious American novelists.” Elizabeth Hardwick admired Rabbit, Run, but thought there was “something insignificant, or understated, or too dimly felt in the heart of Rabbit himself.” As for his sexual frankness, Updike, like his contemporaries, had “not decided or discovered in what way this frankness will change the work itself. It cannot be merely interlarded like suet in the roast.”

By the time Couples came out, John Updike had already published four novels, three story collections, two poetry collections, and a volume of assorted prose. He had been called, by the New York Times Book Review, “the most significant young novelist in America,” and had been sent by the State Department on a tour of the Communist bloc. And yet there was a growing sense that he had not made a major statement on the issues of the day. He could describe a barn well enough, but to what end? The man whose name will be forever asterisked with the insult David Foster Wallace made famous—“just a penis with a thesaurus”—was thought to be clever but a little small, too decorative, and overly fond of childhood reminiscence. Norman Podhoretz complained that Updike “has very little to say.” John Aldridge put him in “the second or just possibly the third rank of serious American novelists.” Elizabeth Hardwick admired Rabbit, Run, but thought there was “something insignificant, or understated, or too dimly felt in the heart of Rabbit himself.” As for his sexual frankness, Updike, like his contemporaries, had “not decided or discovered in what way this frankness will change the work itself. It cannot be merely interlarded like suet in the roast.” The Congo is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world. It was here that

The Congo is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world. It was here that