Ali Boyle in IAI News:

I sometimes play a game with my cat, Cleo. I stand around the corner from her, just out of sight. She starts to sneak towards me. When I poke my head around the corner to look at her, she freezes. When I pull back, she carries on sneaking. Eventually, she pounces on my ankles.

I sometimes play a game with my cat, Cleo. I stand around the corner from her, just out of sight. She starts to sneak towards me. When I poke my head around the corner to look at her, she freezes. When I pull back, she carries on sneaking. Eventually, she pounces on my ankles.

In my mind, we’re playing Statues – the children’s game in which the aim is to sneak up on someone without that person seeing you move. But Cleo can’t be thinking of it that way. So, what’s she thinking? Why does she freeze when my head pops around the corner?

Here’s an obvious answer. She’s trying to attack my ankles. She stops when I stick my head out because she knows I can see her, and knows that if I see her coming I’ll know she’s coming, and she’ll lose the element of surprise.

This obvious answer assumes that Cleo is a mindreader. Now, I don’t mean by this that she’s telepathic. Psychologists and philosophers use the term ‘mindreader’ to refer to someone with the ability to ascribe mental states to others. I’m a mindreader in this sense, and so are you – because we can make judgments about what others are thinking, feeling, seeing, and so on. Our answer assumes that Cleo is a mindreader because it involves her making a judgment about what I can see (her approaching), and about what I know (an attack is imminent).

But can Cleo really ‘read minds’? Does she even have a concept of seeing or knowing? To be clear, my question is not whether Cleo sees and knows things, but whether she knows that I see and know things – or that any animal does. When she hunts, does she consider whether her prey knows she’s there? When she faces off with the neighbour’s cat, does she realise that it sees her?

More here.

Slate today is taking the rare step of publishing a letter someone sent us from inside an ongoing bank robbery. We have done so at the request of the author, who is currently robbing a bank, but would like to minimize his exposure to criminal charges from this whole bank robbery thing now that it seems to be going south. We invite you to submit a question about this essay or our vetting process

Slate today is taking the rare step of publishing a letter someone sent us from inside an ongoing bank robbery. We have done so at the request of the author, who is currently robbing a bank, but would like to minimize his exposure to criminal charges from this whole bank robbery thing now that it seems to be going south. We invite you to submit a question about this essay or our vetting process  It’s a rare children’s book, Heneghan notes, that doesn’t have a wilderness interlude; but then he has to consider exactly what is meant by “wilderness”. It is doubtful if nature at its most extreme and untrammelled can exist in the world today, since even the wildest of wild places are shaped by the activities of people as well as natural forces. He cites as an example the Burren in Co Clare, along with the bogs and mountainy country of the west of Ireland ‑ all territories that have evolved over millennia as a consequence of human intervention in the landscape. However, if wilderness, or quasi-wilderness, occurs at one end of the environmental spectrum and the densely populated city at the other end, what occupies the space between them is denoted by the word “pastoral”, and this makes a highly fruitful ground for children’s stories. Section Two of Beasts at Bedtime considers the pastoral impulse in writing for children, with due attention paid to Pooh, Peter Rabbit, Rat and Mole, Bilbo Baggins, the Ugly Duckling and others. (But we miss Rupert, whose picture-strip adventures encompass many aspects of pastoral: woodland, meadowland, fields, hills, seaside, streams, lily ponds, cottage gardens … all the way to underground caverns and cannibal islands. And you’d have to say that Rupert, in one sense, goes one better than Winnie-the-Pooh. In AA Milne’s stories a little boy plays with his bear; with Rupert, the little boy is the bear.)

It’s a rare children’s book, Heneghan notes, that doesn’t have a wilderness interlude; but then he has to consider exactly what is meant by “wilderness”. It is doubtful if nature at its most extreme and untrammelled can exist in the world today, since even the wildest of wild places are shaped by the activities of people as well as natural forces. He cites as an example the Burren in Co Clare, along with the bogs and mountainy country of the west of Ireland ‑ all territories that have evolved over millennia as a consequence of human intervention in the landscape. However, if wilderness, or quasi-wilderness, occurs at one end of the environmental spectrum and the densely populated city at the other end, what occupies the space between them is denoted by the word “pastoral”, and this makes a highly fruitful ground for children’s stories. Section Two of Beasts at Bedtime considers the pastoral impulse in writing for children, with due attention paid to Pooh, Peter Rabbit, Rat and Mole, Bilbo Baggins, the Ugly Duckling and others. (But we miss Rupert, whose picture-strip adventures encompass many aspects of pastoral: woodland, meadowland, fields, hills, seaside, streams, lily ponds, cottage gardens … all the way to underground caverns and cannibal islands. And you’d have to say that Rupert, in one sense, goes one better than Winnie-the-Pooh. In AA Milne’s stories a little boy plays with his bear; with Rupert, the little boy is the bear.) From March through July, some lucky thousands in New York could experience the perihelion of one of our most noble projects. “A Synthesis of Intuitions,” Piper’s retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the largest the museum has ever devoted to a living artist, brought together work from 1965 to 2016, the latter date representing the cusp of the latest national crisis. Organized by Christophe Cherix and David Platzker at MoMA, along with Connie Butler at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, where a version of the show opens on October 7,1 the exhibition collected the works of a genius who has given herself to a relentless, life-affirming engagement—in philosophy, in art—with the fundamental operations of xenophobia. It contained records of the investigation of certain tools (dance, reason, confrontation, aggressive politesse, dance) to understand and target and then transform the mechanisms that divide people into groups and distribute resources according to unjust criteria.

From March through July, some lucky thousands in New York could experience the perihelion of one of our most noble projects. “A Synthesis of Intuitions,” Piper’s retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the largest the museum has ever devoted to a living artist, brought together work from 1965 to 2016, the latter date representing the cusp of the latest national crisis. Organized by Christophe Cherix and David Platzker at MoMA, along with Connie Butler at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, where a version of the show opens on October 7,1 the exhibition collected the works of a genius who has given herself to a relentless, life-affirming engagement—in philosophy, in art—with the fundamental operations of xenophobia. It contained records of the investigation of certain tools (dance, reason, confrontation, aggressive politesse, dance) to understand and target and then transform the mechanisms that divide people into groups and distribute resources according to unjust criteria. In the spring of 1815, already beset by poor health, Percy Shelley was tormented by a spell of coughing so vicious, and a pain in his side so intense, that he became convinced he was about to die. “An eminent physician,” wrote Mary Godwin (soon to be Mary Shelley), diagnosed the malady as consumption, and so, throughout the spring and well into the summer, the poet was obsessed with thoughts of his mortality. He began imagining what might become of Mary were he indeed to perish. Not until early September did Shelley recover, yet his general gloom lingered; after all, there had been a death earlier that year—that of the couple’s first child. Having moved with Mary into a cottage on the border of Berkshire and Surrey, a hundred yards or so from the Great Park at Windsor, Shelley wrote the death-inflected “Alastor; or The Spirit of Solitude” and a work that more directly addressed his anxieties about his future wife: a Gothic, angst-ridden poem called “The Sunset.”

In the spring of 1815, already beset by poor health, Percy Shelley was tormented by a spell of coughing so vicious, and a pain in his side so intense, that he became convinced he was about to die. “An eminent physician,” wrote Mary Godwin (soon to be Mary Shelley), diagnosed the malady as consumption, and so, throughout the spring and well into the summer, the poet was obsessed with thoughts of his mortality. He began imagining what might become of Mary were he indeed to perish. Not until early September did Shelley recover, yet his general gloom lingered; after all, there had been a death earlier that year—that of the couple’s first child. Having moved with Mary into a cottage on the border of Berkshire and Surrey, a hundred yards or so from the Great Park at Windsor, Shelley wrote the death-inflected “Alastor; or The Spirit of Solitude” and a work that more directly addressed his anxieties about his future wife: a Gothic, angst-ridden poem called “The Sunset.” Jahangir’s course is directed by a woeman and is now, as it were, shut up by her so that all justice or care of anything or publique affayres either sleeps or depends on her, who is most unaccesible than any goddesse or mistery of heathen impietye.” So wrote in 1617 the disgruntled Thomas Roe, then British ambassador to the Mughal court, of the influence of the emperor’s 20th wife, Nur Jahan. Men everywhere, it seems, were threatened by the rise and reign of women, their racism and misogyny tied together in knots.

Jahangir’s course is directed by a woeman and is now, as it were, shut up by her so that all justice or care of anything or publique affayres either sleeps or depends on her, who is most unaccesible than any goddesse or mistery of heathen impietye.” So wrote in 1617 the disgruntled Thomas Roe, then British ambassador to the Mughal court, of the influence of the emperor’s 20th wife, Nur Jahan. Men everywhere, it seems, were threatened by the rise and reign of women, their racism and misogyny tied together in knots. The first test of a new gene-editing tool in people has yielded early clues that the strategy—an infusion that turns the liver into an enzyme factory—could help treat a rare, inherited metabolic disorder. Today, the biotech company Sangamo Therapeutics in Richmond, California, reported data suggesting that two patients with Hunter syndrome are now making small amounts of a crucial enzyme that their bodies previously could not produce. But the company is still a long way from providing evidence that the new method can improve Hunter patients’ health. Hunter syndrome results from a mutation in a gene for an enzyme that cells need to break down certain sugars. When these sugars, called glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), build up in tissues, they damage organs such as the heart and lungs, sometimes leading to developmental delays, brain damage, and early death. The new treatment uses a gene-editing tool called zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs). ZFNs were developed earlier than CRISPR, the hugely popular gene-editing tool, and Sangamo has already used them to edit cells in a dish that were then

The first test of a new gene-editing tool in people has yielded early clues that the strategy—an infusion that turns the liver into an enzyme factory—could help treat a rare, inherited metabolic disorder. Today, the biotech company Sangamo Therapeutics in Richmond, California, reported data suggesting that two patients with Hunter syndrome are now making small amounts of a crucial enzyme that their bodies previously could not produce. But the company is still a long way from providing evidence that the new method can improve Hunter patients’ health. Hunter syndrome results from a mutation in a gene for an enzyme that cells need to break down certain sugars. When these sugars, called glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), build up in tissues, they damage organs such as the heart and lungs, sometimes leading to developmental delays, brain damage, and early death. The new treatment uses a gene-editing tool called zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs). ZFNs were developed earlier than CRISPR, the hugely popular gene-editing tool, and Sangamo has already used them to edit cells in a dish that were then  On Sunday 28 April 1996, Martin Bryant was awoken by his alarm at 6am. He said goodbye to his girlfriend as she left the house, ate some breakfast, and set the burglar alarm before leaving his Hobart residence, as usual. He stopped briefly to purchase a coffee in the small town of Forcett, where he asked the cashier to “boil the kettle less time.” He then drove to the nearby town of Port Arthur, originally a colonial-era convict settlement populated only by a few hundred people. It was here that Bryant would go on to use the two rifles and a shotgun stashed inside a sports bag on the passenger seat of his car to perpetrate the worst massacre in modern Australian history. By the time it was over, 35 people were dead and a further 23 were left wounded.

On Sunday 28 April 1996, Martin Bryant was awoken by his alarm at 6am. He said goodbye to his girlfriend as she left the house, ate some breakfast, and set the burglar alarm before leaving his Hobart residence, as usual. He stopped briefly to purchase a coffee in the small town of Forcett, where he asked the cashier to “boil the kettle less time.” He then drove to the nearby town of Port Arthur, originally a colonial-era convict settlement populated only by a few hundred people. It was here that Bryant would go on to use the two rifles and a shotgun stashed inside a sports bag on the passenger seat of his car to perpetrate the worst massacre in modern Australian history. By the time it was over, 35 people were dead and a further 23 were left wounded. Sabine Hossenfelder’s Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray is an unusual book, at once intensely personal and intellectually hard-edged. Although I disagree with it on many points, I recommend the book both as a well-written, moving intellectual autobiography and as an excellent exposition of some frontiers of foundational theoretical physics, largely told through dialogs with leading figures in the field.

Sabine Hossenfelder’s Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray is an unusual book, at once intensely personal and intellectually hard-edged. Although I disagree with it on many points, I recommend the book both as a well-written, moving intellectual autobiography and as an excellent exposition of some frontiers of foundational theoretical physics, largely told through dialogs with leading figures in the field. Francis Fukuyama is tired of talking about the end of history. Thirty years ago, he published a wonky

Francis Fukuyama is tired of talking about the end of history. Thirty years ago, he published a wonky  AMERICAN POETRY IS thriving. American poetry is in decline. The poetry audience has never been bigger. The audience has dropped to historic lows. The mass media ignores poetry. The media has rediscovered it. There have never been so many opportunities for poets. American poets find fewer options each year. The university provides a vibrant environment for poets. Academic culture has become stagnant and remote. Literary bohemias have been destroyed by gentrification and rising real estate prices. New bohemias have emerged across the nation. All of these contradictory statements are true, and all of them are false, depending on your point of view. The state of American poetry is a tale of two cities.

AMERICAN POETRY IS thriving. American poetry is in decline. The poetry audience has never been bigger. The audience has dropped to historic lows. The mass media ignores poetry. The media has rediscovered it. There have never been so many opportunities for poets. American poets find fewer options each year. The university provides a vibrant environment for poets. Academic culture has become stagnant and remote. Literary bohemias have been destroyed by gentrification and rising real estate prices. New bohemias have emerged across the nation. All of these contradictory statements are true, and all of them are false, depending on your point of view. The state of American poetry is a tale of two cities. Why, then, should we take a new look at Fabro? In my opinion, it is because of what he can tell us about the possibilities of sculpture.

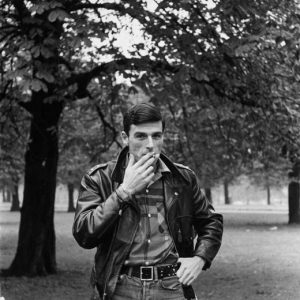

Why, then, should we take a new look at Fabro? In my opinion, it is because of what he can tell us about the possibilities of sculpture. The accepted view of Gunn, as Kleinzahler sums it up, was that in 1954 he ‘had removed himself to California where he would, as was alleged over and over, begin his long decline, undone by sunshine, LSD, queer sex and free verse’. Kleinzahler sought to challenge this idea of the softening of Gunn’s brain in California. ‘The city,’ he wrote, ‘will become his central theme, character and event being played out on its street corners, in its rooms, bars, bathhouses, stairwells, taxis.’ Kleinzahler also notes that, even when the poems became more relaxed and contemporary, ‘the “I” of the poetry’ carried ‘almost no tangible personality. This can be upsetting or disappointing to the contemporary reader, especially the American reader, accustomed to the dramatic personalities behind the voices in recent poetry: Lowell, Berryman, Sexton, Ginsberg, Plath, Hughes, et al. Even in Larkin there exists a strong, identifiable persona, no matter how recessive the tone.’

The accepted view of Gunn, as Kleinzahler sums it up, was that in 1954 he ‘had removed himself to California where he would, as was alleged over and over, begin his long decline, undone by sunshine, LSD, queer sex and free verse’. Kleinzahler sought to challenge this idea of the softening of Gunn’s brain in California. ‘The city,’ he wrote, ‘will become his central theme, character and event being played out on its street corners, in its rooms, bars, bathhouses, stairwells, taxis.’ Kleinzahler also notes that, even when the poems became more relaxed and contemporary, ‘the “I” of the poetry’ carried ‘almost no tangible personality. This can be upsetting or disappointing to the contemporary reader, especially the American reader, accustomed to the dramatic personalities behind the voices in recent poetry: Lowell, Berryman, Sexton, Ginsberg, Plath, Hughes, et al. Even in Larkin there exists a strong, identifiable persona, no matter how recessive the tone.’ In the middle of the day on 11 April 2014, a hooded gunman ambushed Gakirah Barnes on the streets of Chicago’s South Side. A volley of bullets struck her in the chest, jaw and neck. The 17-year-old died in a hospital bed two hours later. To many, her death was just another grim statistic from a city that has been struggling with gun violence. Last year, around 3,500 people were shot in Chicago, Illinois, of which 246 were aged 16 or younger; 38 of those children never celebrated another birthday. But Barnes’s death was unusual for several reasons. She was a young woman in an epidemic of violence that largely affects black men. She also had an Internet following. Barnes had a reputation as a ‘hitta’ — or killer — with rumours of at least two dead bodies to her credit. Although never charged with murder, she embraced the persona, posing in photos and videos with guns in her hands and making threats against rival gangs on Twitter. In a morbid modern irony, it’s likely that she revealed her location in real time to her killer through a tweet. Police have yet to charge anyone in connection with her murder.

In the middle of the day on 11 April 2014, a hooded gunman ambushed Gakirah Barnes on the streets of Chicago’s South Side. A volley of bullets struck her in the chest, jaw and neck. The 17-year-old died in a hospital bed two hours later. To many, her death was just another grim statistic from a city that has been struggling with gun violence. Last year, around 3,500 people were shot in Chicago, Illinois, of which 246 were aged 16 or younger; 38 of those children never celebrated another birthday. But Barnes’s death was unusual for several reasons. She was a young woman in an epidemic of violence that largely affects black men. She also had an Internet following. Barnes had a reputation as a ‘hitta’ — or killer — with rumours of at least two dead bodies to her credit. Although never charged with murder, she embraced the persona, posing in photos and videos with guns in her hands and making threats against rival gangs on Twitter. In a morbid modern irony, it’s likely that she revealed her location in real time to her killer through a tweet. Police have yet to charge anyone in connection with her murder. What are the limits of freedom of speech? It is a pressing question at a moment when conspiracy theories help to fuel fascist politics around the world. Shouldn’t liberal democracy promote a full airing of all possibilities, even false and bizarre ones, because the truth will eventually prevail?

What are the limits of freedom of speech? It is a pressing question at a moment when conspiracy theories help to fuel fascist politics around the world. Shouldn’t liberal democracy promote a full airing of all possibilities, even false and bizarre ones, because the truth will eventually prevail?