Category: Recommended Reading

How feelings took over the world

William Davies in The Guardian:

On a late Friday afternoon in November last year, police were called to London’s Oxford Circus for reasons described as “terror-related”. Oxford Circus underground station was evacuated, producing a crush of people as they made for the exits. Reports circulated of shots being fired, and photos and video appeared online of crowds fleeing the area, with heavily armed police officers heading in the opposite direction. Amid the panic, it was unclear where exactly the threat was emanating from, or whether there might be a number of attacks going on simultaneously, as had occurred in Paris two years earlier. Armed police stormed Selfridges department store, while shoppers were instructed to evacuate the building. Inside the shop at the time was the pop star Olly Murs, who tweeted to nearly 8 million followers: “Fuck everyone get out of Selfridge now gun shots!!” As shoppers in the store made for the exits, others were rushing in at the same time, producing a stampede.

On a late Friday afternoon in November last year, police were called to London’s Oxford Circus for reasons described as “terror-related”. Oxford Circus underground station was evacuated, producing a crush of people as they made for the exits. Reports circulated of shots being fired, and photos and video appeared online of crowds fleeing the area, with heavily armed police officers heading in the opposite direction. Amid the panic, it was unclear where exactly the threat was emanating from, or whether there might be a number of attacks going on simultaneously, as had occurred in Paris two years earlier. Armed police stormed Selfridges department store, while shoppers were instructed to evacuate the building. Inside the shop at the time was the pop star Olly Murs, who tweeted to nearly 8 million followers: “Fuck everyone get out of Selfridge now gun shots!!” As shoppers in the store made for the exits, others were rushing in at the same time, producing a stampede.

Smartphones and social media meant that this whole event was recorded, shared and discussed in real time. The police attempted to quell the panic using their own Twitter feed, but this was more than offset by the sense of alarm that was engulfing other observers. Far-right campaigner Tommy Robinson tweeted that this “looks like another jihad attack in London”. The Daily Mail unearthed an innocent tweet from 10 days earlier, which had described a “lorry stopped on a pavement in Oxford Street”, and used this as a basis on which to tweet “Gunshots fired” as armed police officers surrounded Oxford Circus station after “lorry ploughs into pedestrians”. The media were not so much reporting facts, as serving to synchronise attention and emotion across a watching public.

How Scientists Can Learn About Human Behavior From Closed-Circuit TV

Anne Nassauer in Smithsonian:

In a 2012 YouTube video of an attempted robbery in California, a strange scene unfolds. Two robbers enter the Circle T Market in Riverbank. One carries a large assault rifle, an AK-47. Upon seeing them, the clerk behind the counter puts his hands up. Yet the elderly store owner finds the weapon absurdly big and casually walks up to the robbers, laughing. His shoulders are relaxed and he points the palms of his hands up as if asking them whether they are serious. Both perpetrators are startled upon seeing the elderly man laughing at them. One runs away, while the one with the AK-47 freezes, is tackled, and is later arrested by police. They had robbed numerous stores before.

In a 2012 YouTube video of an attempted robbery in California, a strange scene unfolds. Two robbers enter the Circle T Market in Riverbank. One carries a large assault rifle, an AK-47. Upon seeing them, the clerk behind the counter puts his hands up. Yet the elderly store owner finds the weapon absurdly big and casually walks up to the robbers, laughing. His shoulders are relaxed and he points the palms of his hands up as if asking them whether they are serious. Both perpetrators are startled upon seeing the elderly man laughing at them. One runs away, while the one with the AK-47 freezes, is tackled, and is later arrested by police. They had robbed numerous stores before.

Analyzing videos captured on CCTV, mobile phones, or body cameras and uploaded to YouTube now provides first-hand insight into a variety of similar situations. And there are a lot of videos to watch. In 2013, 31 percent of internet users online posted a video to a website. And on YouTube alone, more than 300 hours of video footage are uploaded every minute. Many of these videos capture our behavior at weddings and concerts, protests and revolutions, and tsunamis and earthquakes. Taboos become obsolete as more types of events are uploaded, from birth to live-streamed murder. While some of these developments are contentious, their scientific potential to understand how social life happens can’t be ignored. This ever-expanding cache of recordings may have drastic implications for our understanding of human behavior.

More here.

Sunday Poem

My Last Résumé

When I was a troubadour

When I was an astronaut

When I was a pirate

You should have seen my closet

You would have loved my shoes.

Kindly consider my application

Even though your position is filled.

This is my stash of snow globes

This is my favorite whip

This is a picture of me with a macaw

This is a song I almost could sing.

When I was a freight train

When I was a satellite

When I was a campfire

You should have seen the starburst

You should have tasted my tomato.

I feel sorry for you I’m unqualified

This is my finest tube of toothpaste

This is when I rode like the raj on a yak

This is the gasoline this is the match.

When I was Hegel’s dialectic

When I was something Rothko forgot

When I was moonlight paving the street

You should have seen the roiling shore

You should have heard the swarm of bees.

by Joseph Di Prisco

from Sight Lines from the Cheap Seats

Rare Bird Books, 2017

Saturday, September 8, 2018

In Yasmina Reza’s Novel, a Dinner Party Descends Into Chaos — and Then Tragedy

Erica Wagner in the New York Times:

It could all go wrong in an instant. In Yasmina Reza’s unsettling new novel, Elisabeth, the narrator, looks back on an evening in a Paris suburb that began in the most ordinary way — a casual evening party for family, friends and neighbors — and ended in catastrophe. The nature of the disaster unfolds across a brisk 200 pages, but it is foreshadowed from the very beginning, when Elisabeth observes her neighbor, Jean-Lino, rigid in an uncomfortable chair, surrounded by the detritus of the festivities, “all the leavings of the party arranged in an optimistic moment. Who can determine the starting point of events?”

It could all go wrong in an instant. In Yasmina Reza’s unsettling new novel, Elisabeth, the narrator, looks back on an evening in a Paris suburb that began in the most ordinary way — a casual evening party for family, friends and neighbors — and ended in catastrophe. The nature of the disaster unfolds across a brisk 200 pages, but it is foreshadowed from the very beginning, when Elisabeth observes her neighbor, Jean-Lino, rigid in an uncomfortable chair, surrounded by the detritus of the festivities, “all the leavings of the party arranged in an optimistic moment. Who can determine the starting point of events?”

On the surface, Elisabeth leads a placid, unexceptional life. She works as a patent engineer at the Pasteur Institute in the city; what she actually does all day, however, remains a mystery. She is married to Pierre, a math professor. “I’m happy with my husband,” she says, but then undercuts that claim: “He loves me even when I look bad, which is not at all reassuring.” At 62, she worries about getting older; she buys anti-aging products recommended by Gwyneth Paltrow and Cate Blanchett, though she disapproves of herself for doing so. She has what appears to be a casual friendship with Jean-Lino; she doesn’t much like his wife, Lydie.

More here.

The Strange Numbers That Birthed Modern Algebra

Charlie Wood in Quanta:

Imagine winding the hour hand of a clock back from 3 o’clock to noon. Mathematicians have long known how to describe this rotation as a simple multiplication: A number representing the initial position of the hour hand on the plane is multiplied by another constant number. But is a similar trick possible for describing rotations through space? Common sense says yes, but William Hamilton, one of the most prolific mathematicians of the 19th century, struggled for more than a decade to find the math for describing rotations in three dimensions. The unlikely solution led him to the third of just four number systems that abide by a close analog of standard arithmetic and helped spur the rise of modern algebra.

Imagine winding the hour hand of a clock back from 3 o’clock to noon. Mathematicians have long known how to describe this rotation as a simple multiplication: A number representing the initial position of the hour hand on the plane is multiplied by another constant number. But is a similar trick possible for describing rotations through space? Common sense says yes, but William Hamilton, one of the most prolific mathematicians of the 19th century, struggled for more than a decade to find the math for describing rotations in three dimensions. The unlikely solution led him to the third of just four number systems that abide by a close analog of standard arithmetic and helped spur the rise of modern algebra.

The real numbers form the first such number system. A sequence of numbers that can be ordered from least to greatest, the reals include all the familiar characters we learn in school, like –3.7, 5–√ and 42. Renaissance algebraists stumbled upon the second system of numbers that can be added, subtracted, multiplied and divided when they realized that solving certain equations demanded a new number, i, that didn’t fit anywhere on the real number line. They took the first steps off that line and into the “complex plane,” where misleadingly named “imaginary” numbers couple with real numbers like capital letters pair with numerals in the game of Battleship. In this planar world, “complex numbers” represent arrows that you can slide around with addition and subtraction or turn and stretch with multiplication and division.

More here.

How Assad Made Truth a Casualty of War

Muhammad Idrees Ahmad in the New York Review of Books:

On February 22, 2012, when the British photojournalist Paul Conroy survived the artillery barrage that killed Marie Colvin, he was rushed to a place of greater danger. Bashar al-Assad’s war of repression has killed civilians indiscriminately, but its targeting of medical facilities has been systematic. Hospitals are the most endangered spaces in opposition-held areas. Of the 492 medical facilities destroyed in the war, Physicians for Human Rights attributes the destruction of 446 to Assad and his allies. The UN Commission of Inquiry has charged the regime and its allies with having “systematically targeted medical facilities… and intentionally attacking medical personnel.” With a pierced abdomen and a fist-sized hole in his thigh, Conroy was carried to hospital under a hail of mortar fire. It was the only hospital in Baba Amr, the besieged Homs neighborhood Colvin and Conroy had been reporting from—and it had no anaesthetics. As the hospital’s only doctor cut away Conroy’s torn muscles and stapled his wounds, Conroy had to dull the pain with three cigarettes.

On February 22, 2012, when the British photojournalist Paul Conroy survived the artillery barrage that killed Marie Colvin, he was rushed to a place of greater danger. Bashar al-Assad’s war of repression has killed civilians indiscriminately, but its targeting of medical facilities has been systematic. Hospitals are the most endangered spaces in opposition-held areas. Of the 492 medical facilities destroyed in the war, Physicians for Human Rights attributes the destruction of 446 to Assad and his allies. The UN Commission of Inquiry has charged the regime and its allies with having “systematically targeted medical facilities… and intentionally attacking medical personnel.” With a pierced abdomen and a fist-sized hole in his thigh, Conroy was carried to hospital under a hail of mortar fire. It was the only hospital in Baba Amr, the besieged Homs neighborhood Colvin and Conroy had been reporting from—and it had no anaesthetics. As the hospital’s only doctor cut away Conroy’s torn muscles and stapled his wounds, Conroy had to dull the pain with three cigarettes.

More here.

See a NASA Physicist’s Incredible Origami

What Are the Biggest Problems Facing Us in the 21st Century?

Bill Gates in The New York Times:

The human mind wants to worry. This is not necessarily a bad thing — after all, if a bear is stalking you, worrying about it may well save your life. Although most of us don’t need to lose too much sleep over bears these days, modern life does present plenty of other reasons for concern: terrorism, climate change, the rise of A.I., encroachments on our privacy, even the apparent decline of international cooperation.

The human mind wants to worry. This is not necessarily a bad thing — after all, if a bear is stalking you, worrying about it may well save your life. Although most of us don’t need to lose too much sleep over bears these days, modern life does present plenty of other reasons for concern: terrorism, climate change, the rise of A.I., encroachments on our privacy, even the apparent decline of international cooperation.

In his fascinating new book, “21 Lessons for the 21st Century,” the historian Yuval Noah Harari creates a useful framework for confronting these fears. While his previous best sellers, “Sapiens” and “Homo Deus,” covered the past and future respectively, his new book is all about the present. The trick for putting an end to our anxieties, he suggests, is not to stop worrying. It’s to know which things to worry about, and how much to worry about them. As he writes in his introduction: “What are today’s greatest challenges and most important changes? What should we pay attention to? What should we teach our kids?” These are admittedly big questions, and this is a sweeping book. There are chapters on work, war, nationalism, religion, immigration, education and 15 other weighty matters. But its title is a misnomer. Although you will find a few concrete lessons scattered throughout, Harari mostly resists handy prescriptions. He’s more interested in defining the terms of the discussion and giving you historical and philosophical perspective.

More here.

Friday, September 7, 2018

Mattering is a more urgent concept than meaning: An Interview with Rebecca Goldstein

Paula Erizanu at IAI News:

You’re currently working on a book on mattering. What do we mean when we say that something, or someone, matters to us?

The notion of mattering is intimately linked with the notion of attention. To say that something matters is to assert that attention is due it, the kind of attention that both recognises and reveals its reality. Something that matters has a nature that demands to be known, and the knowledge may yield other attitudes and behaviour due it. If I say that something doesn’t matter, I’m saying that it’s not worth paying attention to.

The notion of mattering is intimately linked with the notion of attention. To say that something matters is to assert that attention is due it, the kind of attention that both recognises and reveals its reality. Something that matters has a nature that demands to be known, and the knowledge may yield other attitudes and behaviour due it. If I say that something doesn’t matter, I’m saying that it’s not worth paying attention to.

And the notion of mattering is also normative, meaning that it implies an ought, an obligation—namely the obligation to pay appropriate attention to it. I think there are objective truths about which things matter. I believe it is a demonstrable moral truth that all humans matter, which isn’t, of course, to assert that only humans matter.

I first became preoccupied with the concept of mattering when I was writing my first book, The Mind-Body Problem—which wasn’t a work of philosophy but rather of fiction. I don’t think this was an accident. A novelist must think out the motivations of her characters, and our strivings to matter — to demonstrate that what we are and what we do are worthy of appropriate attention — are key in understanding human motivation. The concept of mattering stretches across the divide between empirical psychology and moral philosophy.

More here.

We know music is pleasurable, the question is why? Many answers have been proposed: perhaps none are quite right

Roger Mathew Grant in Aeon:

Can a melody provide us with pleasure? Plato certainly thought so, as do many today. But it’s incredibly difficult to discern just how this comes to pass. Is it something about the flow and shape of a tune that encourages you to predict its direction and follow along? Or is it that the lyrics of a certain song describe a scene that reminds you of a joyful time? Perhaps the melody is so familiar that you’ve simply come to identify with it.

Can a melody provide us with pleasure? Plato certainly thought so, as do many today. But it’s incredibly difficult to discern just how this comes to pass. Is it something about the flow and shape of a tune that encourages you to predict its direction and follow along? Or is it that the lyrics of a certain song describe a scene that reminds you of a joyful time? Perhaps the melody is so familiar that you’ve simply come to identify with it.

Critics have proposed variations on all of these ideas as explanatory mechanisms for musical pleasure, though there remains no critical consensus. The story of their attempts and difficulties forms one vital component of Western intellectual history, and its many misdirections are revealing to trace in their own right. In early modern Europe, theorists generally adopted a view inspired by Aristotle’s Poetics: they supposed that the tones of a melody could work together with a text in order to imitate the natural world. Music, in this view, was something of a live soundtrack to a multimedia representation. It could assist in an analogic way with the depiction of the natural sentiments or features of the world captured in the language of its poetry, thereby eliciting a pleasurable response. Determining specifically how this worked was, in fact, the elusive goal set out at the opening of René Descartes’s first complete treatise, the Compendium Musicae (written in 1618). Unfortunately, Descartes never made it past a simple elaboration of musical preliminaries. He felt that, in order to make the connection to pleasure and passion, he would need a more detailed account of the movements of the soul.

More here. [Thanks to Seema Dhody Natesan.]

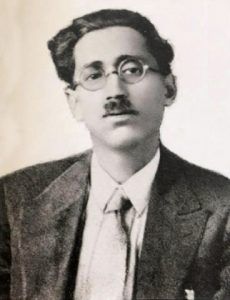

The First Feminist Urdu Writer

Zoovia Hamiduddin in Dawn:

Mirza Azeem Baig Chughtai has been maligned, misunderstood and pigeonholed as a humourist — which indeed he was; his short stories ‘Yakka’ and ‘Al Shizri’ have been immortalised by the rendition of the legendary Zia Mohyeddin. But other erroneous theories about him have also been made. In ‘Literary Notes: Azeem Baig Chughtai, Sadomasochist or Playful Humourist?’ published in Dawn on Aug 22, 2016, for example, Rauf Parekh considered speculation by literary stalwarts Dr Muhammad Sadiq and Dr Vazeer Agha who believed Chughtai suffered from “depression” and was a “sadomasochist”. Not so. The tantalising title of the piece aside, Parekh rightfully stated that these writers were being “perhaps, all too unsympathetic.”

Mirza Azeem Baig Chughtai has been maligned, misunderstood and pigeonholed as a humourist — which indeed he was; his short stories ‘Yakka’ and ‘Al Shizri’ have been immortalised by the rendition of the legendary Zia Mohyeddin. But other erroneous theories about him have also been made. In ‘Literary Notes: Azeem Baig Chughtai, Sadomasochist or Playful Humourist?’ published in Dawn on Aug 22, 2016, for example, Rauf Parekh considered speculation by literary stalwarts Dr Muhammad Sadiq and Dr Vazeer Agha who believed Chughtai suffered from “depression” and was a “sadomasochist”. Not so. The tantalising title of the piece aside, Parekh rightfully stated that these writers were being “perhaps, all too unsympathetic.”

Parekh references Chughtai’s sister, the author Ismat Chughtai, as saying that her brother was irreverent towards many traditional ideas. Thus, in looking past the obvious humour in his writings, it becomes clear that Chughtai was, in fact, one of the earliest proponents of feminism in the subcontinent.

More here.

Lawrence Lessig: How the Net destroyed democracy

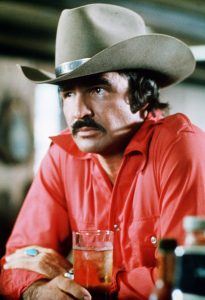

The Friendly, Sexy Stardom of Burt Reynolds

Sarah Larson at The New Yorker:

For pop-culture enthusiasts of the seventies and eighties, reports of the death of Burt Reynolds, at age eighty-two, of a heart attack, in Jupiter, Florida, may have come as an unexpected shock. Some of us imagined him as eternally youthful, wisecracking, knowingly amused. Reynolds was a genial presence who seemed to have it all—in his heyday, he was the country’s top box-office star for five years; later, he lived in a sprawling estate called Valhalla—and remain a good sport. (His memoir, from 2015, is called “But Enough About Me.”) He was an amiable king of machismo, hairy chests, and highway-focussed buddy comedies, and his friendly sexiness—onscreen and on the covers of tabloids and glossy magazines—was for many years a constant. His groundbreaking centerfold in Cosmopolitan, from 1972, in which he stretched out, naked, on a bearskin rug, embodied his affable sensuality. “He was handsome, humorous, wonderful body, frisky,” Helen Gurley Brown later said, of choosing him for the shoot.

For pop-culture enthusiasts of the seventies and eighties, reports of the death of Burt Reynolds, at age eighty-two, of a heart attack, in Jupiter, Florida, may have come as an unexpected shock. Some of us imagined him as eternally youthful, wisecracking, knowingly amused. Reynolds was a genial presence who seemed to have it all—in his heyday, he was the country’s top box-office star for five years; later, he lived in a sprawling estate called Valhalla—and remain a good sport. (His memoir, from 2015, is called “But Enough About Me.”) He was an amiable king of machismo, hairy chests, and highway-focussed buddy comedies, and his friendly sexiness—onscreen and on the covers of tabloids and glossy magazines—was for many years a constant. His groundbreaking centerfold in Cosmopolitan, from 1972, in which he stretched out, naked, on a bearskin rug, embodied his affable sensuality. “He was handsome, humorous, wonderful body, frisky,” Helen Gurley Brown later said, of choosing him for the shoot.

more here.

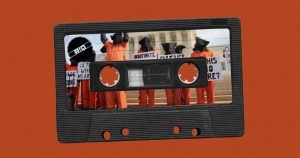

The Soundtrack of Hell

Scott G. Bruce at Literary Hub:

One of the more unusual methods employed by US interrogators to break the will of detainees during harsh interrogation at Abu Ghraib, Bagram, Mosul, and elsewhere is the use of loud music. The 2006 edition of the US Army’s field manual for interrogation advocated the use of abusive sound as a method of interrogation, a practice corroborated by former detainees who were subject to this abuse. At Guantánamo, inmates reported being held in chains without food or water in total darkness “with loud rap or heavy metal blaring for weeks at a time.” This music played several roles during interrogation. It provoked fear, distress, and disorientation, crowding out the thoughts of the detainee and bending their will to the interrogators’. Even when played at excruciatingly high volume (often as loud as 100 decibels during harsh interrogation, the equivalent of a jackhammer), music leaves no marks on detainees and sheds no blood; it inflicts severe physical and psychological pain without betraying any evidence of its source.

One of the more unusual methods employed by US interrogators to break the will of detainees during harsh interrogation at Abu Ghraib, Bagram, Mosul, and elsewhere is the use of loud music. The 2006 edition of the US Army’s field manual for interrogation advocated the use of abusive sound as a method of interrogation, a practice corroborated by former detainees who were subject to this abuse. At Guantánamo, inmates reported being held in chains without food or water in total darkness “with loud rap or heavy metal blaring for weeks at a time.” This music played several roles during interrogation. It provoked fear, distress, and disorientation, crowding out the thoughts of the detainee and bending their will to the interrogators’. Even when played at excruciatingly high volume (often as loud as 100 decibels during harsh interrogation, the equivalent of a jackhammer), music leaves no marks on detainees and sheds no blood; it inflicts severe physical and psychological pain without betraying any evidence of its source.

more here.

J. L. Austin: A Return to Common Sense

Guy Longworth at the TLS:

Austin thought that philosophical perplexities were generated by failing to attend to such distinctions and, in particular, by failing to acknowledge the importance of the illocutionary act. One example arises from attempts to treat stating something as a locutionary rather than an illocutionary act, and so as something that is achieved just by uttering a meaningful sentence. The apparent variety of things we do in speaking would then be treated as mere differences in perlocutionary effects that arise from stating something in different circumstances. Thus, for example, uttering the sentence, “I promise that I’ll be home for dinner”, would be treated as a way of stating something about oneself, rather than as a way of promising. Promising itself would be a perlocutionary effect of making such a statement about oneself. It would consequently be perplexing to try to understand what precisely one was stating about oneself, and how stating it could bring about promising. Furthermore, the locutionary treatment makes it too easy to state something, requiring only that one utter a meaningful sentence; whereas, in fact, stating, like promising, is dependent on propitious circumstances for its successful performance. The treatment leads to puzzlement about what was stated by the utterance of some meaningful sentence in cases in which absence of the required circumstances means that no such stating occurred.

Austin thought that philosophical perplexities were generated by failing to attend to such distinctions and, in particular, by failing to acknowledge the importance of the illocutionary act. One example arises from attempts to treat stating something as a locutionary rather than an illocutionary act, and so as something that is achieved just by uttering a meaningful sentence. The apparent variety of things we do in speaking would then be treated as mere differences in perlocutionary effects that arise from stating something in different circumstances. Thus, for example, uttering the sentence, “I promise that I’ll be home for dinner”, would be treated as a way of stating something about oneself, rather than as a way of promising. Promising itself would be a perlocutionary effect of making such a statement about oneself. It would consequently be perplexing to try to understand what precisely one was stating about oneself, and how stating it could bring about promising. Furthermore, the locutionary treatment makes it too easy to state something, requiring only that one utter a meaningful sentence; whereas, in fact, stating, like promising, is dependent on propitious circumstances for its successful performance. The treatment leads to puzzlement about what was stated by the utterance of some meaningful sentence in cases in which absence of the required circumstances means that no such stating occurred.

more here.

Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters on Grief

Rainer Maria Rilke in The Paris Review:

Throughout his life, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875 -1926) wrote letters to close friends as well as individuals who had read his poetry but did not know him personally. At the time of his death in 1926 at the age of 51, Rilke had written over 14,000 letters which he considered to be as significant and worthy of publication as his poetry and prose. Among this vast correspondence are 23 letters of condolence. For nearly 100 years, most of their sometimes bracing and always powerful insights have been hidden in plain sight, or rather buried in a disorganized and partly irretrievable set of publications and archives on two continents. They have now been gathered for the first time into a short volume that offers Rilke’s highly original and accessible reflections on loss, grief and mortality. Together they tell a story leading from an unflinching and honest acknowledgment of death to transformation, just as Rilke’s well-known Letters to a Young Poet recounts the story from unflinching self-reckoning and the acceptance of solitude to serious self-transformation. Taken individually, each of the letters on loss, which Rilke wrote to different recipients but with the same single-minded intent to assist someone in mourning, may offer solace for anyone dealing with a personal loss. What can we say in the face of loss, when words seem too frail and ordinary to convey grief and soothe the pain? How can we provide solace for the bereaved, when even time, as Rilke stresses over and over, cannot properly console but only “put things in order”? These letters offer guidance in the effort to recover our voice during periods of loss and grief, and not to let even the most devastating experiences overwhelm, numb and silence us. —Ulrich Baer

Throughout his life, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875 -1926) wrote letters to close friends as well as individuals who had read his poetry but did not know him personally. At the time of his death in 1926 at the age of 51, Rilke had written over 14,000 letters which he considered to be as significant and worthy of publication as his poetry and prose. Among this vast correspondence are 23 letters of condolence. For nearly 100 years, most of their sometimes bracing and always powerful insights have been hidden in plain sight, or rather buried in a disorganized and partly irretrievable set of publications and archives on two continents. They have now been gathered for the first time into a short volume that offers Rilke’s highly original and accessible reflections on loss, grief and mortality. Together they tell a story leading from an unflinching and honest acknowledgment of death to transformation, just as Rilke’s well-known Letters to a Young Poet recounts the story from unflinching self-reckoning and the acceptance of solitude to serious self-transformation. Taken individually, each of the letters on loss, which Rilke wrote to different recipients but with the same single-minded intent to assist someone in mourning, may offer solace for anyone dealing with a personal loss. What can we say in the face of loss, when words seem too frail and ordinary to convey grief and soothe the pain? How can we provide solace for the bereaved, when even time, as Rilke stresses over and over, cannot properly console but only “put things in order”? These letters offer guidance in the effort to recover our voice during periods of loss and grief, and not to let even the most devastating experiences overwhelm, numb and silence us. —Ulrich Baer

To: Mimi Romanelli

(1877 – 1970), the youngest sister of the Italian art dealer Pietro Romanelli known for her beauty and musical talent. Rilke stayed in her family’s small hotel in Venice in 1907. They had a brief romantic relationship and maintained a long correspondence thereafter.

Oberneuland near Bremen (Germany)

Sunday, the 8th of December, 1907

There is death in life, and it astonishes me that we pretend to ignore this: death, whose unforgiving presence we experience with each change we survive because we must learn to die slowly. We must learn to die: That is all of life. To prepare gradually the masterpiece of a proud and supreme death, of a death where chance plays no part, of a well-made, beatific and enthusiastic death of the kind the saints knew to shape. Of a long-ripened death that effaces its hateful name and is nothing but a gesture that returns those laws to the anonymous universe which have been recognized and rescued over the course of an intensely accomplished life. It is this idea of death, which has developed inside of me since childhood from one painful experience to the next and which compels me to humbly endure the small death so that I may become worthy of the one which wants us to be great.

More here.

Zora Neale Hurston in the Spotlight

Brandon J. Dixon in Harvard Magazine:

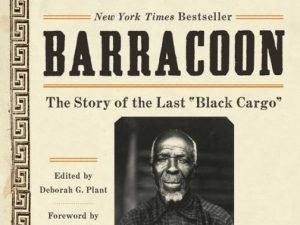

Two Harvard scholars have recently contributed to the conversation on Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo,” a previously unpublished 1931 manuscript by Zora Neale Hurston, and its significance for African-American history and literature. Published by HarperCollins this April, the much-anticipated book recounts the life of Cudjo Lewis, who was believed to be the last living survivor of the slave trade.

Two Harvard scholars have recently contributed to the conversation on Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo,” a previously unpublished 1931 manuscript by Zora Neale Hurston, and its significance for African-American history and literature. Published by HarperCollins this April, the much-anticipated book recounts the life of Cudjo Lewis, who was believed to be the last living survivor of the slave trade.

Hurston is best known for her short stories and novels, including Their Eyes Were Watching God, but she originally studied anthropology at Barnard: she traversed the country to collect African-American folk traditions and published research on Haitian voodoo. Though billed as the last testament to the horrors of the slave trade, Barracoon is, at its core, an anthropological work: Hurston represents Lewis in his own voice, in a dialect that turned white publishers away from the novel in 1931. Lewis’s story—of his capture in West Africa, transportation abroad the Clotilda in 1860 (the last vessel known to have carried slaves to the United States), enslavement, emancipation, and survival under the harsh Jim Crow laws of the South—is interwoven with the wealth of cultural knowledge Hurston elicited from him. To highlight the nuances of the text, Nicholas Rinehart ’14, a Ph.D. candidate in English, and Marshall scholar Rebecca Panovka ’16 have in separate articles drawn attention to the African folklore tradition Barracoon unearths, and the work’s tangled publication history.

More here.

Friday Poem

On Calling the Cops

It took us this long to slow our dying

down to a languid and sensible pace

wherein the sugar might claim each our limbs

but never in one fell and vicious swoop

how irony does when the voice you use

to summon a state-hired cavalry

is also the one used to beg of them

to not create a Calvary where you stand

and make you a Christ begat from gun-smoke

so rules the nation’s practice of mishap

which reads the skin like a type of license

before any righteous explanation

just as the weapon gives its sovereign word

puckers its steel mouth to decide your name byRasheed Copeland

from Split This Rock

Thursday, September 6, 2018

The Trump administration is stranger than fiction

Amitava Kumar in The Globe and Mail:

As a writer, I’m forever obliged to ask what makes a story compelling.

The above question is so much a part of my own thinking that it is impossible to escape it even in other contexts. While reading the news about migrants at the Mexican border, or watching footage of raids by law enforcement, I ask myself which side in the debate is telling the better story.

Let me admit at the outset that this might well be a narrowly professional concern. To the main actors in the scenario, the demands of duty or the plain urgency of survival make such questions irrelevant and even remote. Nevertheless, I find myself giving a desperate cast to my inquiry. To use the language of writing workshops, are lives being lost because the characters in the story are insufficiently fleshed out? Are futures being stolen because someone has lost the plot? Is our society being torn apart because no one is offering a narrative of sufficient complexity?

Once I entertain all those questions, another one arises: Who is telling the true, more urgent, story?

More here.