Mychal Denzel Smith at Bookforum:

On the Other Side of Freedom is filled with short bursts of this kind of beauty. In service of what, though? In twelve chapters covering organizing, identity, activism, and more, Mckesson sets out to provide an “intellectual, pragmatic political framework for a new liberation movement.”But he doesn’t move much beyond poetic rhapsodizing about protest, which he romanticizes to the exclusion of most other aspects of resistance. Indeed, he’s outright dismissive of some. In the chapter “On Organizing,” he recounts his frustrations at a training session led by a national organizer, which wasn’t, he felt, useful to the situation in Ferguson. This could have been a great opportunity to describe new directions that activism might take, but his description of the meeting’s shortcomings are frustratingly vague. He is unhappy with the notion of the “top-down model in which an organizing body or institution confers knowledge, gives direction, grants permission.” The protesters, he points out, don’t need this kind of guidance—they already possess the skills necessary for effective activism. “The tactics that were effective in bringing about change in the sixties, seventies, and eighties are well known to all,” he explains. “And thus we needed new tactics for a new time.” And what are those new tactics? “To ignore the role of social media as difference-maker in organizing is perilous.”

On the Other Side of Freedom is filled with short bursts of this kind of beauty. In service of what, though? In twelve chapters covering organizing, identity, activism, and more, Mckesson sets out to provide an “intellectual, pragmatic political framework for a new liberation movement.”But he doesn’t move much beyond poetic rhapsodizing about protest, which he romanticizes to the exclusion of most other aspects of resistance. Indeed, he’s outright dismissive of some. In the chapter “On Organizing,” he recounts his frustrations at a training session led by a national organizer, which wasn’t, he felt, useful to the situation in Ferguson. This could have been a great opportunity to describe new directions that activism might take, but his description of the meeting’s shortcomings are frustratingly vague. He is unhappy with the notion of the “top-down model in which an organizing body or institution confers knowledge, gives direction, grants permission.” The protesters, he points out, don’t need this kind of guidance—they already possess the skills necessary for effective activism. “The tactics that were effective in bringing about change in the sixties, seventies, and eighties are well known to all,” he explains. “And thus we needed new tactics for a new time.” And what are those new tactics? “To ignore the role of social media as difference-maker in organizing is perilous.”

more here.

[Bob] Woodward has never been a very good writer, but his literary failures have never been more apparent than in Fear, where the mismatch between the prose and the protagonists is almost avant-garde. Many sentences are overwrought to the point of being nonsensical. (“The first act of the Bannon drama is his appearance—the old military field jacket over multiple tennis polo shirts. The second act is his demeanor—aggressive, certain and loud.”) His reliance on cliché is laughable, particularly in his descriptions of characters with whom all of the book’s readers are already well-acquainted. Kellyanne Conway is “feisty” and Reince Priebus—a source whom Woodward conspicuously flatters—is an “empire builder.” Mohammed bin Salman is “charming” and has “vision, energy,” which suggests Woodward has been reading Tom Friedman columns. Jared Kushner has a “self-possessed, almost aristocratic bearing” (possibly the most self-evidently false detail in a book full of them). And the late John McCain is (of course) “outspoken” and a “maverick.” Woodward seems to have a fascination with the bodies and demeanor of older, military men: both Jim Mattis and H.R. McMaster have “ramrod-straight posture,” and the latter is described as “high and tight,” even though he is conspicuously bald. Trump goes “through the roof” twice in a single chapter. And so on.

[Bob] Woodward has never been a very good writer, but his literary failures have never been more apparent than in Fear, where the mismatch between the prose and the protagonists is almost avant-garde. Many sentences are overwrought to the point of being nonsensical. (“The first act of the Bannon drama is his appearance—the old military field jacket over multiple tennis polo shirts. The second act is his demeanor—aggressive, certain and loud.”) His reliance on cliché is laughable, particularly in his descriptions of characters with whom all of the book’s readers are already well-acquainted. Kellyanne Conway is “feisty” and Reince Priebus—a source whom Woodward conspicuously flatters—is an “empire builder.” Mohammed bin Salman is “charming” and has “vision, energy,” which suggests Woodward has been reading Tom Friedman columns. Jared Kushner has a “self-possessed, almost aristocratic bearing” (possibly the most self-evidently false detail in a book full of them). And the late John McCain is (of course) “outspoken” and a “maverick.” Woodward seems to have a fascination with the bodies and demeanor of older, military men: both Jim Mattis and H.R. McMaster have “ramrod-straight posture,” and the latter is described as “high and tight,” even though he is conspicuously bald. Trump goes “through the roof” twice in a single chapter. And so on. One week last month, when it was unseasonably cold and rainy—which I loved because I was in a depression—there were suddenly mice flurrying everywhere in the courtyard, in and out of a pneumatic HVAC unit they installed last summer. The mice seemed extra small. Maybe they were babies. Maybe it was because two summers ago we had raccoons in the yard. Then last summer, rats, and a few roaches.

One week last month, when it was unseasonably cold and rainy—which I loved because I was in a depression—there were suddenly mice flurrying everywhere in the courtyard, in and out of a pneumatic HVAC unit they installed last summer. The mice seemed extra small. Maybe they were babies. Maybe it was because two summers ago we had raccoons in the yard. Then last summer, rats, and a few roaches. Norman Ernest Borlaug was an American agronomist and humanitarian born in Iowa in 1914. After receiving a PhD from the University of Minnesota in 1944, Borlaug moved to Mexico to work on agricultural development for the Rockefeller Foundation. Although Borlaug’s taskforce was initiated to teach Mexican farmers methods to increase food productivity, he quickly became obsessed with developing better (i.e., higher-yielding and pest-and-climate resistant) crops.

Norman Ernest Borlaug was an American agronomist and humanitarian born in Iowa in 1914. After receiving a PhD from the University of Minnesota in 1944, Borlaug moved to Mexico to work on agricultural development for the Rockefeller Foundation. Although Borlaug’s taskforce was initiated to teach Mexican farmers methods to increase food productivity, he quickly became obsessed with developing better (i.e., higher-yielding and pest-and-climate resistant) crops. In an age of widening inequality, Walter Scheidel believes he has cracked the code on how to overcome it. In “The Great Leveler”, the Stanford professor posits that throughout history, economic inequality has only been rectified by one of the “Four Horsemen of Leveling”: warfare, revolution, state collapse and plague.

In an age of widening inequality, Walter Scheidel believes he has cracked the code on how to overcome it. In “The Great Leveler”, the Stanford professor posits that throughout history, economic inequality has only been rectified by one of the “Four Horsemen of Leveling”: warfare, revolution, state collapse and plague. So he sets off, offering the things Sinclair fans will know well: the rhythms of urban walks that turn into sentences and paragraphs, the tracing and retracing of old and new ground, the eternal return to the churches of Nicholas Hawksmoor that he has been performing since his Lud Heat of 1975, long before Peter Ackroyd got in on the act. Also the cadences of mordancy and mortality, the attraction to putrefaction. The streets and walls of Sinclair City have the odour and texture of things found floating on canals, but are iridescent with unexpected beauty.

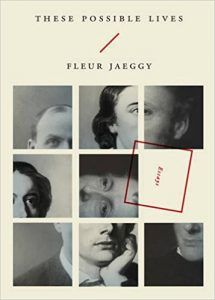

So he sets off, offering the things Sinclair fans will know well: the rhythms of urban walks that turn into sentences and paragraphs, the tracing and retracing of old and new ground, the eternal return to the churches of Nicholas Hawksmoor that he has been performing since his Lud Heat of 1975, long before Peter Ackroyd got in on the act. Also the cadences of mordancy and mortality, the attraction to putrefaction. The streets and walls of Sinclair City have the odour and texture of things found floating on canals, but are iridescent with unexpected beauty. Consider Oliver Munday’s striking cover for These Possible Lives, one of the slim, sharp, dark works of Swiss/Italian author Fleur Jaeggy. The tile motif, bearing eight gray, equal segments from historical portraits of the book’s subjects, is immediately captivating; one glimpses mouths and eyes, poignant gazes into a mercurial unknown, or unsettling direct eye contact that seems to say, there are truths within this small book, but whose truth may they be? This obfuscation is furthered by Munday’s decision to create a ninth tile without image, choosing instead a tilted red box containing that imprecise, strange word, “Essays.” I pick up the book, read the title, These Possible Lives, and think to myself, what is possible about historically recorded lives. A simple red backslash wants to point me down, to the broken mosaic of possibility below, however, I realize red warns, and the indirect backslash conveys hesitation. This cover does a wonderful job trying to dissuade one from any clear preconceptions of the text within, while equally stoking my intense curiosity.

Consider Oliver Munday’s striking cover for These Possible Lives, one of the slim, sharp, dark works of Swiss/Italian author Fleur Jaeggy. The tile motif, bearing eight gray, equal segments from historical portraits of the book’s subjects, is immediately captivating; one glimpses mouths and eyes, poignant gazes into a mercurial unknown, or unsettling direct eye contact that seems to say, there are truths within this small book, but whose truth may they be? This obfuscation is furthered by Munday’s decision to create a ninth tile without image, choosing instead a tilted red box containing that imprecise, strange word, “Essays.” I pick up the book, read the title, These Possible Lives, and think to myself, what is possible about historically recorded lives. A simple red backslash wants to point me down, to the broken mosaic of possibility below, however, I realize red warns, and the indirect backslash conveys hesitation. This cover does a wonderful job trying to dissuade one from any clear preconceptions of the text within, while equally stoking my intense curiosity. The manuscript for My Life With

The manuscript for My Life With  It isn’t until you start reading it that you realize how much we need a book like this one at this particular moment. “These Truths,” by

It isn’t until you start reading it that you realize how much we need a book like this one at this particular moment. “These Truths,” by  There are images on the walls of caves, whether we put them there or not. Or, more precisely, we create images on the walls of caves, whether with charcoal and manganese or simply with our imaginations. Michelangelo’s well-known claim that he simply released from stone what was already there is straightforwardly true of Paleolithic artists. They placed their lines where the contours already suggested animal motion.

There are images on the walls of caves, whether we put them there or not. Or, more precisely, we create images on the walls of caves, whether with charcoal and manganese or simply with our imaginations. Michelangelo’s well-known claim that he simply released from stone what was already there is straightforwardly true of Paleolithic artists. They placed their lines where the contours already suggested animal motion. In the 1940s, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department began trying to move bighorns back into their historic habitats. Those relocations continue today, and they’ve been increasingly successful at restoring the extirpated herds. But the lost animals aren’t just lost bodies. Their knowledge also died with them—and that is not easily replaced.

In the 1940s, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department began trying to move bighorns back into their historic habitats. Those relocations continue today, and they’ve been increasingly successful at restoring the extirpated herds. But the lost animals aren’t just lost bodies. Their knowledge also died with them—and that is not easily replaced. ‘If we don’t do this

‘If we don’t do this THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FACEBOOK

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FACEBOOK When the British philosopher Gilbert Ryle was asked whether he read novels, he famously replied, without missing a beat, “Oh, yes—all six, every year.” And without missing a beat we get the joke, of course, not because we believe that Jane Austen’s novels throw all others into the shadows (though we do), and not because they bear annual rereading (though they do), but rather because we all know—or think we know—that she wrote six of them.

When the British philosopher Gilbert Ryle was asked whether he read novels, he famously replied, without missing a beat, “Oh, yes—all six, every year.” And without missing a beat we get the joke, of course, not because we believe that Jane Austen’s novels throw all others into the shadows (though we do), and not because they bear annual rereading (though they do), but rather because we all know—or think we know—that she wrote six of them. A massive study of nearly 4,000 variants in a gene associated with cancer could help to pinpoint people at risk for breast or ovarian tumours. The information is sorely needed: millions of people have had their BRCA1 gene sequenced. Some variations in the DNA sequence of BRCA1are linked to breast and ovarian cancer; others are thought to be safe. But

A massive study of nearly 4,000 variants in a gene associated with cancer could help to pinpoint people at risk for breast or ovarian tumours. The information is sorely needed: millions of people have had their BRCA1 gene sequenced. Some variations in the DNA sequence of BRCA1are linked to breast and ovarian cancer; others are thought to be safe. But