Peter Haldeman in the New York Times:

The Pioneer Valley in western Massachusetts is a cradle of social progress — a place where L.G.B.T.Q. is often followed by I.A. (for intersex and asexual), there’s a Stonewall Center (now 33 years old), and gender-nonconforming parents have a nickname of choice (it’s “Baba”).

The Pioneer Valley in western Massachusetts is a cradle of social progress — a place where L.G.B.T.Q. is often followed by I.A. (for intersex and asexual), there’s a Stonewall Center (now 33 years old), and gender-nonconforming parents have a nickname of choice (it’s “Baba”).

On a Maple-lined street here in Northampton, in a white gablefront house, lives one such Baba, a.k.a. Andrea Lawlor, a gender queer novelist and visiting lecturer at Mt. Holyoke College; Lawlor, who uses the pronoun they, shares the first floor rooms with their girlfriend, their 5-year-old child, and their child’s sprawling Lego constructions. The second floor is occupied by Lawlor’s best friend of 25 years, Jordy Rosenberg, a transgender novelist who teaches 18th century literature, gender and sexuality studies, and critical theory at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Sometimes they call their home a “queer commune.”

Lawlor’s debut novel, “Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl,” set in the 1990s and featuring a shape-shifting (and sex-obsessed) protagonist, was published last year by Rescue Press — and received enough attention that Vintage/Anchor and Picador will reissue the book next spring.

More here.

In a publication

In a publication On the evening of 28 October, as they absorbed the election of far-right Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, British leftists declared “socialism or barbarism”. The slogan was assumed by some to be a Corbynite coinage. But it was first popularised more than a century ago in war-ravaged Europe.

On the evening of 28 October, as they absorbed the election of far-right Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, British leftists declared “socialism or barbarism”. The slogan was assumed by some to be a Corbynite coinage. But it was first popularised more than a century ago in war-ravaged Europe. The Incas left no doubt that theirs was a sophisticated, technologically savvy civilisation. At its height in the 15th century, it was the largest empire in the Americas, extending almost 5000 kilometres from modern-day Ecuador to Chile. These were the people who built Machu Picchu, a royal estate perched in the clouds, and an extensive network of paved roads complete with suspension bridges crafted from woven grass. But the paradox of the Incas is that despite all this sophistication they never learned to write.

The Incas left no doubt that theirs was a sophisticated, technologically savvy civilisation. At its height in the 15th century, it was the largest empire in the Americas, extending almost 5000 kilometres from modern-day Ecuador to Chile. These were the people who built Machu Picchu, a royal estate perched in the clouds, and an extensive network of paved roads complete with suspension bridges crafted from woven grass. But the paradox of the Incas is that despite all this sophistication they never learned to write. Before ancient humans

Before ancient humans Men of action present a problem for decent modern democrats. For the very term “men of action” is a euphemism for men accomplished in war, and no public figure is more suspect these days than the warlike man. When Winston Churchill called Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) “the greatest man of action born in Europe since Julius Caesar,” he meant to praise Napoleon in the highest terms, but for many, such praise is fraught with peril. After all, Julius Caesar, named dictator in perpetuity, placed the Roman Republic in mortal danger and died a tyrant’s death; the most famous of his assassins, Marcus Junius Brutus, is remembered as a paragon of republican virtue, though it proved impossible to restore the Republic after Caesar’s day.

Men of action present a problem for decent modern democrats. For the very term “men of action” is a euphemism for men accomplished in war, and no public figure is more suspect these days than the warlike man. When Winston Churchill called Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) “the greatest man of action born in Europe since Julius Caesar,” he meant to praise Napoleon in the highest terms, but for many, such praise is fraught with peril. After all, Julius Caesar, named dictator in perpetuity, placed the Roman Republic in mortal danger and died a tyrant’s death; the most famous of his assassins, Marcus Junius Brutus, is remembered as a paragon of republican virtue, though it proved impossible to restore the Republic after Caesar’s day. Paul Krugman, blogger, fiat-currency enthusiast and winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics earlier this year justified his scepticism about cryptocurrencies in the New York Times. He asked readers to give him a clear answer to the question: what is the problem cryptocurrency solves? He wrote: ‘Governments have occasionally abused the privilege of creating fiat money, but for the most part governments and central banks exercise restraint.’ He added that, unlike bitcoin, ‘fiat currencies have underlying value because men with guns say they do. And this means that their value isn’t a bubble that can collapse if people lose faith.’

Paul Krugman, blogger, fiat-currency enthusiast and winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics earlier this year justified his scepticism about cryptocurrencies in the New York Times. He asked readers to give him a clear answer to the question: what is the problem cryptocurrency solves? He wrote: ‘Governments have occasionally abused the privilege of creating fiat money, but for the most part governments and central banks exercise restraint.’ He added that, unlike bitcoin, ‘fiat currencies have underlying value because men with guns say they do. And this means that their value isn’t a bubble that can collapse if people lose faith.’ It’s a huge day for archaeologists and anyone interested in the history of America’s first settlers. Findings from three new genetics studies—all released today—are presenting a fascinating, yet complex, picture of the first people in North and South America, and how they spread and diversified across two continents.

It’s a huge day for archaeologists and anyone interested in the history of America’s first settlers. Findings from three new genetics studies—all released today—are presenting a fascinating, yet complex, picture of the first people in North and South America, and how they spread and diversified across two continents. It’s fun to be in the exciting, chaotic, youthful days of the podcast, when anything goes and experimentation is the order of the day. So today’s show is something different: a solo effort, featuring just me talking without any guests to cramp my style. This won’t be the usual format, but I suspect it will happen from time to time. Feel free to chime in below on how often you think alternative formats should be part of the mix.

It’s fun to be in the exciting, chaotic, youthful days of the podcast, when anything goes and experimentation is the order of the day. So today’s show is something different: a solo effort, featuring just me talking without any guests to cramp my style. This won’t be the usual format, but I suspect it will happen from time to time. Feel free to chime in below on how often you think alternative formats should be part of the mix.

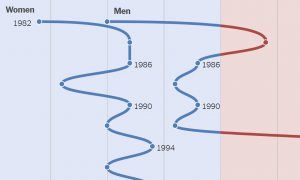

In the 2016 presidential election, 55 percent of white women voted for Republicans. And this year, the group backed Democrats and Republicans evenly.

In the 2016 presidential election, 55 percent of white women voted for Republicans. And this year, the group backed Democrats and Republicans evenly.

The fascination of what’s difficult,” wrote WB Yeats, “has dried the sap out of my veins … ” In the press coverage of this year’s Man Booker prize winner, Anna Burns’s

The fascination of what’s difficult,” wrote WB Yeats, “has dried the sap out of my veins … ” In the press coverage of this year’s Man Booker prize winner, Anna Burns’s  The futurist philosopher Yuval Noah Harari worries about a lot. He worries that Silicon Valley is undermining democracy and ushering in a dystopian hellscape in which voting is obsolete. He worries that by creating powerful influence machines to control billions of minds, the big tech companies are destroying the idea of a sovereign individual with free will. He worries that because the technological revolution’s work requires so few laborers, Silicon Valley is creating a tiny ruling class and a teeming, furious “useless class.” But lately, Mr. Harari is anxious about something much more personal. If this is his harrowing warning, then why do Silicon Valley C.E.O.s love him so? “One possibility is that my message is not threatening to them, and so they embrace it?” a puzzled Mr. Harari said one afternoon in October. “For me, that’s more worrying. Maybe I’m missing something?”

The futurist philosopher Yuval Noah Harari worries about a lot. He worries that Silicon Valley is undermining democracy and ushering in a dystopian hellscape in which voting is obsolete. He worries that by creating powerful influence machines to control billions of minds, the big tech companies are destroying the idea of a sovereign individual with free will. He worries that because the technological revolution’s work requires so few laborers, Silicon Valley is creating a tiny ruling class and a teeming, furious “useless class.” But lately, Mr. Harari is anxious about something much more personal. If this is his harrowing warning, then why do Silicon Valley C.E.O.s love him so? “One possibility is that my message is not threatening to them, and so they embrace it?” a puzzled Mr. Harari said one afternoon in October. “For me, that’s more worrying. Maybe I’m missing something?”