by Mary Hrovat

Before the second was defined in terms of the characteristics of the cesium atom, before leap seconds or leap days or Julian dates or the Gregorian calendar, before clocks, even before the sundial and the hourglass, there were sunrise, sunset, and shadows.

Before the second was defined in terms of the characteristics of the cesium atom, before leap seconds or leap days or Julian dates or the Gregorian calendar, before clocks, even before the sundial and the hourglass, there were sunrise, sunset, and shadows.

I’ve been thinking about timekeeping using shadows because a tulip tree in my backyard casts a shadow that traces a semicircle over the lawn on sunny days and moonlit nights, like the hand of a clock. The shadow is longest and most noticeable at this time of year, when the sun crosses the sky low in the south, and on summer nights around full moon. (The full moon crosses the sky low in the south in the summer, when the sun is riding high in the north.) However, I can see it year-round, given adequate sunlight or moonlight, although its appearance varies depending on the position of the sun or moon. I enjoy seeing this subtle demonstration of daily and seasonal cycles.

The gnomon on a sundial (the part that casts a shadow) was probably inspired by natural objects like this tree that cast useful shadows and roughly indicate the time of day. The first human-made gnomons were vertical poles or towers. For example, Egyptian obelisks, in addition to being tributes to gods or markers celebrating a ruler’s achievements, acted as gnomons, and their shadows marked the time of day for a city.

Sundials of various types were developed as these early timekeepers were refined by aligning the gnomon with Earth’s rotational axis and adding a dial that marks divisions in time. In addition, the natural or solar hours, which vary in length throughout the year if you’re not near the equator, were eventually replaced by hours of equal length. Thus was timekeeping made more useful but also distanced somewhat from its roots in solar time, particularly when clock time had to be coordinated across different regions and eventually across the globe. Read more »

I joined Facebook in 2008, and for the most part, I have benefited from being on it. Lately, however, I have wondered whether I should delete my Facebook account. As a philosopher with a special interest in ethics, I am using “should” in the moral sense. That is, in light of recent events implicating Facebook in objectionable behavior, is there a duty to leave it?

I joined Facebook in 2008, and for the most part, I have benefited from being on it. Lately, however, I have wondered whether I should delete my Facebook account. As a philosopher with a special interest in ethics, I am using “should” in the moral sense. That is, in light of recent events implicating Facebook in objectionable behavior, is there a duty to leave it?

If you hate Assange because of his role in the 2016 race, please take a deep breath and consider what a criminal charge that does not involve the 2016 election might mean. An Assange prosecution could give the Trump presidency broad new powers to put Trump’s media “enemies” in jail, instead of just yanking a credential or two. The

If you hate Assange because of his role in the 2016 race, please take a deep breath and consider what a criminal charge that does not involve the 2016 election might mean. An Assange prosecution could give the Trump presidency broad new powers to put Trump’s media “enemies” in jail, instead of just yanking a credential or two. The

This episode features political scientist

This episode features political scientist  Confronting the

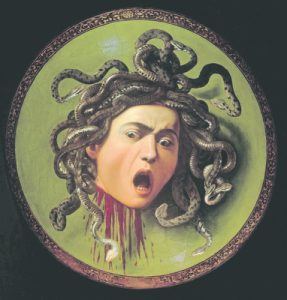

Confronting the  Two Southern belles on the run get catcalled one too many times by the same schlubby dude; they blow up his truck. A couple of rough-and-ready French chicks talk their way into an architect’s house—his place is “like a drawing by a well-balanced child,” as is his smug, suave, symmetrical mug—and point their Smith & Wessons at him, all the while admiring both his book collection and his calm under pressure. “It’s clear to me,” one of them tells him affectionately, “that you stand out from our past encounters.” Then she shoots him in the face. “Get your fucking hands off me, goddamn it!” yells a leader of the National Women’s Political Caucus at the 1972 Democratic National Convention, addressing the member of the white-guy network-news crowd who is trying to restrain her as she rages over their failure to cover her group’s contributions. “The next son of a bitch that touches a woman is gonna get kicked in the balls.” A ten-year-old African American girl, menaced by a white boy, picks up a chunk of brick and aims it at him. When an avowed pussy-grabber tries to win a presidential debate against his female opponent by trotting out a bunch of women who’ve accused her husband of rape and other misconduct, a woman journalist takes to cable news to defend her beloved historic candidate, “shaking and red-faced with rage.”

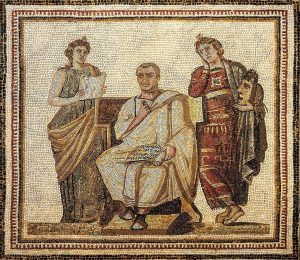

Two Southern belles on the run get catcalled one too many times by the same schlubby dude; they blow up his truck. A couple of rough-and-ready French chicks talk their way into an architect’s house—his place is “like a drawing by a well-balanced child,” as is his smug, suave, symmetrical mug—and point their Smith & Wessons at him, all the while admiring both his book collection and his calm under pressure. “It’s clear to me,” one of them tells him affectionately, “that you stand out from our past encounters.” Then she shoots him in the face. “Get your fucking hands off me, goddamn it!” yells a leader of the National Women’s Political Caucus at the 1972 Democratic National Convention, addressing the member of the white-guy network-news crowd who is trying to restrain her as she rages over their failure to cover her group’s contributions. “The next son of a bitch that touches a woman is gonna get kicked in the balls.” A ten-year-old African American girl, menaced by a white boy, picks up a chunk of brick and aims it at him. When an avowed pussy-grabber tries to win a presidential debate against his female opponent by trotting out a bunch of women who’ve accused her husband of rape and other misconduct, a woman journalist takes to cable news to defend her beloved historic candidate, “shaking and red-faced with rage.” Since the end of the first century A.D., people have been playing a game with a certain book. In this game, you open the book to a random spot and place your finger on the text; the passage you select will, it is thought, predict your future. If this sounds silly, the results suggest otherwise. The first person known to have played the game was a highborn Roman who was fretting about whether he’d be chosen to follow his cousin, the emperor Trajan, on the throne; after opening the book to this passage—

Since the end of the first century A.D., people have been playing a game with a certain book. In this game, you open the book to a random spot and place your finger on the text; the passage you select will, it is thought, predict your future. If this sounds silly, the results suggest otherwise. The first person known to have played the game was a highborn Roman who was fretting about whether he’d be chosen to follow his cousin, the emperor Trajan, on the throne; after opening the book to this passage— In February of

In February of Brains are important things; they’re where thinking happens. Or are they? The theory of “

Brains are important things; they’re where thinking happens. Or are they? The theory of “ Admiring the great thinkers of the past has become morally hazardous. Praise Immanuel Kant, and you might be reminded that he believed that ‘Humanity is at its greatest perfection in the race of the whites,’ and ‘the yellow Indians do have a meagre talent’. Laud Aristotle, and you’ll have to explain how a genuine sage could have thought that ‘the male is by nature superior and the female inferior, the male ruler and the female subject’.

Admiring the great thinkers of the past has become morally hazardous. Praise Immanuel Kant, and you might be reminded that he believed that ‘Humanity is at its greatest perfection in the race of the whites,’ and ‘the yellow Indians do have a meagre talent’. Laud Aristotle, and you’ll have to explain how a genuine sage could have thought that ‘the male is by nature superior and the female inferior, the male ruler and the female subject’. Give people a sugar pill, they have shown, and those patients — especially if they have one of the chronic, stress-related conditions that register the strongest placebo effects and if the treatment is delivered by someone in whom they have confidence — will improve. Tell someone a normal milkshake is a diet beverage, and his gut will respond as if the drink were low fat. Take athletes to the top of the Alps, put them on exercise machines and hook them to an oxygen tank, and they will perform better than when they are breathing room air — even if room air is all that’s in the tank. Wake a patient from surgery and tell him you’ve done an arthroscopic repair, and his knee gets better even if all you did was knock him out and put a couple of incisions in his skin. Give a drug a fancy name, and it works better than if you don’t.

Give people a sugar pill, they have shown, and those patients — especially if they have one of the chronic, stress-related conditions that register the strongest placebo effects and if the treatment is delivered by someone in whom they have confidence — will improve. Tell someone a normal milkshake is a diet beverage, and his gut will respond as if the drink were low fat. Take athletes to the top of the Alps, put them on exercise machines and hook them to an oxygen tank, and they will perform better than when they are breathing room air — even if room air is all that’s in the tank. Wake a patient from surgery and tell him you’ve done an arthroscopic repair, and his knee gets better even if all you did was knock him out and put a couple of incisions in his skin. Give a drug a fancy name, and it works better than if you don’t. Deborah Chasman: The book focuses on the 2016 election and what made the public sphere so vulnerable to what you call “disinformation, propaganda, and just sheer bullshit.” You resist the idea that technology was the primary driver of that problem, that the manipulation of Facebook’s platform, the Russian intervention, and fake news led to a Trump victory. What did you find in your research that led you to challenge the now common story that extreme polarization has been technologically driven?

Deborah Chasman: The book focuses on the 2016 election and what made the public sphere so vulnerable to what you call “disinformation, propaganda, and just sheer bullshit.” You resist the idea that technology was the primary driver of that problem, that the manipulation of Facebook’s platform, the Russian intervention, and fake news led to a Trump victory. What did you find in your research that led you to challenge the now common story that extreme polarization has been technologically driven?