by Amanda Beth Peery

Mr Cogito is trying to make his soul more porous

like the screen door of a house in the country

letting all the air in.

Mr Cogito wants a soul like a net

catching colors & conversations, catching visions:

the singing through the door of a cathedral

on a crooked street, reaching for angels,

where he and the beggars outside understand

for the first time how to admire God

the crunch of ice in countless machines

the slush moving under boots in the street

& the thickness or click or throat-roll of consonants

in a dozen languages on the rush-hour subway

& the roar of fast traffic like the ocean

& the ocean itself breaking its rolled fists

on rocks and the deep

groaning of the earth — he heard the earth

is firmer here, it helps to hold

the skyscraper’s foundations

over its molten roll — he wants to scoop

the sounds, slick & meat-thick

out of the net of his soul

& feel the life of them in his fingers.

I was lugging several superheavy boxes of dishes up the concrete stairs from the sidewalk to the front door when a guy in a silver suit materialized in front of me. The first rule of moving is that when you pick something up, you don’t put it down until you have it where it goes. This is because picking it up and putting it down are half the battle. So, I tried to go around him.

I was lugging several superheavy boxes of dishes up the concrete stairs from the sidewalk to the front door when a guy in a silver suit materialized in front of me. The first rule of moving is that when you pick something up, you don’t put it down until you have it where it goes. This is because picking it up and putting it down are half the battle. So, I tried to go around him.

The Alps are much grander this morning. I like to think they tiptoed closer in the night, but it’s only an optical illusion created by a local high-pressure system called föhn, which magnifies them and everything else on the horizon. Sitting outside in the loggia, a spacious recessed balcony that resembles a box at the opera, I am audience to many forms of entertainment—weather theater, rainbow theater, sunrise theater, moonrise theater, but best of all, avian theater with its motley cast of bird species performing their life cycles like variations on a theme, in full view.

The Alps are much grander this morning. I like to think they tiptoed closer in the night, but it’s only an optical illusion created by a local high-pressure system called föhn, which magnifies them and everything else on the horizon. Sitting outside in the loggia, a spacious recessed balcony that resembles a box at the opera, I am audience to many forms of entertainment—weather theater, rainbow theater, sunrise theater, moonrise theater, but best of all, avian theater with its motley cast of bird species performing their life cycles like variations on a theme, in full view. When one makes an artwork, something flows from artist to audience. The thing flowing is actually several: concepts, ideas, aesthetic experiences, duration itself, beliefs, attitudes, and probably much more. Artworks work in a similar way to language, although it would be foolish to believe that artworks are language. Their similarities to language end at the transmission from one to another of the things flowing. That’s how language works as well. But for art, as with something like emotion, the flow is vague in how it is sent and received. It seems to me that the best linguistic analogy for what artworks do is located in assertion. Artworks assert a position. Of course it is entirely possible, and even the norm, that their version of assertion is cryptic to the point of being sometimes unintelligible. But assertions don’t need to be crystal clear. One can assert their dominance over another through a series of non-linguistic subtle bodily movements. Likewise, artworks can make assertions through their physical presence.

When one makes an artwork, something flows from artist to audience. The thing flowing is actually several: concepts, ideas, aesthetic experiences, duration itself, beliefs, attitudes, and probably much more. Artworks work in a similar way to language, although it would be foolish to believe that artworks are language. Their similarities to language end at the transmission from one to another of the things flowing. That’s how language works as well. But for art, as with something like emotion, the flow is vague in how it is sent and received. It seems to me that the best linguistic analogy for what artworks do is located in assertion. Artworks assert a position. Of course it is entirely possible, and even the norm, that their version of assertion is cryptic to the point of being sometimes unintelligible. But assertions don’t need to be crystal clear. One can assert their dominance over another through a series of non-linguistic subtle bodily movements. Likewise, artworks can make assertions through their physical presence. Nobody would have the balls today to write The Satanic Verses, let alone publish it,’ the writer Hanif Kureishi told a journalist in 2009. Salman Rushdie’s notorious novel, like Kureishi’s figure of speech, is indeed looking like a relic of a bygone time. When it was published 31 years ago, the global furore was unprecedented. There were protests, book-burnings and riots. Iran’s leader Ayatollah Khomeini called on Muslims to kill Rushdie, a bounty was placed on his head, and there were murders, attempted and successful, of supporters, publishers and translators. The author spent years in hiding.

Nobody would have the balls today to write The Satanic Verses, let alone publish it,’ the writer Hanif Kureishi told a journalist in 2009. Salman Rushdie’s notorious novel, like Kureishi’s figure of speech, is indeed looking like a relic of a bygone time. When it was published 31 years ago, the global furore was unprecedented. There were protests, book-burnings and riots. Iran’s leader Ayatollah Khomeini called on Muslims to kill Rushdie, a bounty was placed on his head, and there were murders, attempted and successful, of supporters, publishers and translators. The author spent years in hiding. I spent much of this week reading and trying to absorb the new and devastating book by one Frédéric Martel on the gayness of the hierarchy at the top of the Catholic Church,

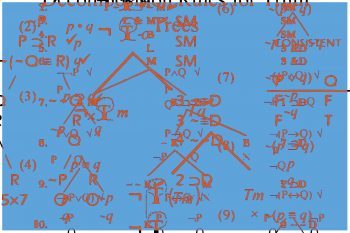

I spent much of this week reading and trying to absorb the new and devastating book by one Frédéric Martel on the gayness of the hierarchy at the top of the Catholic Church,  In 1964, during a lecture at Cornell University, the physicist Richard Feynman articulated a profound mystery about the physical world. He told his listeners to imagine two objects, each gravitationally attracted to the other. How, he asked, should we predict their movements? Feynman identified three approaches, each invoking a different belief about the world. The first approach used Newton’s law of gravity, according to which the objects exert a pull on each other. The second imagined a gravitational field extending through space, which the objects distort. The third applied the principle of least action, which holds that each object moves by following the path that takes the least energy in the least time. All three approaches produced the same, correct prediction. They were three equally useful descriptions of how gravity works.

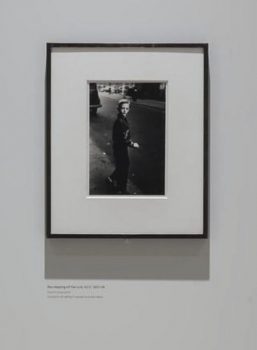

In 1964, during a lecture at Cornell University, the physicist Richard Feynman articulated a profound mystery about the physical world. He told his listeners to imagine two objects, each gravitationally attracted to the other. How, he asked, should we predict their movements? Feynman identified three approaches, each invoking a different belief about the world. The first approach used Newton’s law of gravity, according to which the objects exert a pull on each other. The second imagined a gravitational field extending through space, which the objects distort. The third applied the principle of least action, which holds that each object moves by following the path that takes the least energy in the least time. All three approaches produced the same, correct prediction. They were three equally useful descriptions of how gravity works. My favourite thing is to go where I’ve never been’ wrote the photographer Diane Arbus, the poor little rich Jewish girl who walked on the wild side. Though the journeys she took were not just physical adventures along the boardwalks of Coney Island or to gender-bending night clubs but those in which she explored the rocky terrain of self-definition. From the start of her career she saw the street as a place full of secrets and reflected her subjects – whether children, the rich or poor, it didn’t matter – as isolated and adrift, remote from society and the world around them, caught up in their own reveries and physical space. Her caste of characters appear like metaphors for themselves; each striving to make him or herself the starring role in their own private psychodrama.

My favourite thing is to go where I’ve never been’ wrote the photographer Diane Arbus, the poor little rich Jewish girl who walked on the wild side. Though the journeys she took were not just physical adventures along the boardwalks of Coney Island or to gender-bending night clubs but those in which she explored the rocky terrain of self-definition. From the start of her career she saw the street as a place full of secrets and reflected her subjects – whether children, the rich or poor, it didn’t matter – as isolated and adrift, remote from society and the world around them, caught up in their own reveries and physical space. Her caste of characters appear like metaphors for themselves; each striving to make him or herself the starring role in their own private psychodrama. Some years ago a well-placed German Catholic priest sent me a long letter denouncing a network of gay clergy supposedly centred around Pope Benedict XVI’s private secretary,

Some years ago a well-placed German Catholic priest sent me a long letter denouncing a network of gay clergy supposedly centred around Pope Benedict XVI’s private secretary,  My dear brother, James Cone. Words fail. Any language falls short. Yes, he was a world-historical figure in contemporary theology, no doubt about that. A towering prophetic figure engaging in his mighty critiques and indictment of contemporary Christendom from the vantage point of the least of these, no doubt about that. But I think he would want us to view him through the lens of the Cross and the blood at the foot of that cross. So, I want to begin with an acknowledgement that James Cone was an exemplary figure in a tradition of a people who have been traumatized for 400 years but taught the world so much about healing; terrorized for 400 years and taught the world so much about freedom; hated for 400 years and taught the world so much about love and how to love. James Cone was a love warrior with an intellectual twist, rooted in gutbucket Jim Crow Arkansas, ended up in the top of the theological world but was never seduced by the idles of the world.

My dear brother, James Cone. Words fail. Any language falls short. Yes, he was a world-historical figure in contemporary theology, no doubt about that. A towering prophetic figure engaging in his mighty critiques and indictment of contemporary Christendom from the vantage point of the least of these, no doubt about that. But I think he would want us to view him through the lens of the Cross and the blood at the foot of that cross. So, I want to begin with an acknowledgement that James Cone was an exemplary figure in a tradition of a people who have been traumatized for 400 years but taught the world so much about healing; terrorized for 400 years and taught the world so much about freedom; hated for 400 years and taught the world so much about love and how to love. James Cone was a love warrior with an intellectual twist, rooted in gutbucket Jim Crow Arkansas, ended up in the top of the theological world but was never seduced by the idles of the world. Last Days at Hot Slit, a collection of Dworkin’s writing edited by Johanna Fateman and Amy Scholder, is an invitation “to consider what was lost in the fray,” as Fateman writes in her moving introduction. Hot Slit contains excerpts from all of Dworkin’s major books as well as previously unpublished material, including letters to her parents, university lectures, and a portion of an unfinished end-of-life autobiographical manuscript called My Suicide. The style is strident, enraged, and the conclusions are often stark, bluntly phrased, and difficult to read. Dworkin had reason to be angry: Her life was marked by the kind of male violence that is disturbingly common yet consistently goes unacknowledged. In 1965, when she was eighteen and a student at Bennington College, Dworkin took part in an anti-war demonstration in Manhattan and was arrested. In jail, she was subjected to a violent gynecological exam that I have no word for other than rape. Her decision to write and testify about it caused enormous distress for her parents, who were upset not only at what had happened to their daughter, but by her choice, incomprehensible to them, to talk about it publicly.

Last Days at Hot Slit, a collection of Dworkin’s writing edited by Johanna Fateman and Amy Scholder, is an invitation “to consider what was lost in the fray,” as Fateman writes in her moving introduction. Hot Slit contains excerpts from all of Dworkin’s major books as well as previously unpublished material, including letters to her parents, university lectures, and a portion of an unfinished end-of-life autobiographical manuscript called My Suicide. The style is strident, enraged, and the conclusions are often stark, bluntly phrased, and difficult to read. Dworkin had reason to be angry: Her life was marked by the kind of male violence that is disturbingly common yet consistently goes unacknowledged. In 1965, when she was eighteen and a student at Bennington College, Dworkin took part in an anti-war demonstration in Manhattan and was arrested. In jail, she was subjected to a violent gynecological exam that I have no word for other than rape. Her decision to write and testify about it caused enormous distress for her parents, who were upset not only at what had happened to their daughter, but by her choice, incomprehensible to them, to talk about it publicly. He had not set out to become a professional historian; indeed, at one point he considered becoming a full-time organiser for the party. And although his early work fell in the academic sub-field of economic history, its inspiration was primarily political. For Hobsbawm, as for so many on the left in his generation, the question that needed addressing was the rise and dominance of capitalism: he later reflected that he chose economic history as his field largely because it was the only intellectual space in the academic world at the time where he could pursue his real interests in relations between “base” and “superstructure” in explaining social change. Emotionally, his sympathies were with capitalism’s victims and opponents. One of his early rejected books described industrialism as “almost certainly the most catastrophic historical change which has overwhelmed the common people of the world”, and he began to cultivate his interest in the forms of often unorganised or disguised resistance to it, especially forms of “social banditry” in the countryside.

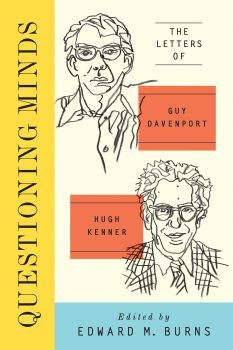

He had not set out to become a professional historian; indeed, at one point he considered becoming a full-time organiser for the party. And although his early work fell in the academic sub-field of economic history, its inspiration was primarily political. For Hobsbawm, as for so many on the left in his generation, the question that needed addressing was the rise and dominance of capitalism: he later reflected that he chose economic history as his field largely because it was the only intellectual space in the academic world at the time where he could pursue his real interests in relations between “base” and “superstructure” in explaining social change. Emotionally, his sympathies were with capitalism’s victims and opponents. One of his early rejected books described industrialism as “almost certainly the most catastrophic historical change which has overwhelmed the common people of the world”, and he began to cultivate his interest in the forms of often unorganised or disguised resistance to it, especially forms of “social banditry” in the countryside. Questioning Minds deserves an audience because it allows readers the privilege of immersion in examinations of Modernist writing, in witnessing earnest and, at times, witty or humorous exchanges, and in seeing how academic (Kenner) and creative (Davenport) projects arise from chance remarks, are worked out (or abandoned), and, now and then, collaborated on, as with Kenner’s book on Flaubert, Joyce and Beckett, The Stoic Comedians(1962), that features Davenport’s illustrations. Both writers urge or hector the other to read, or write, this or that article or book. Kenner encourages Davenport to do extensive translations of the poetry of a particular Greek lyric poet, and this later became Carmina Archilochi: The Fragments of Archilochos (1964). Both interceded to help the other give paid talks or find university positions.

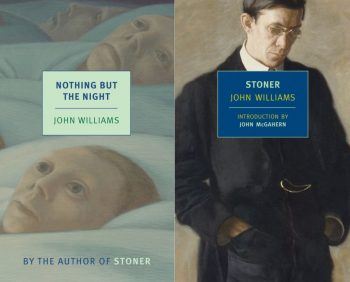

Questioning Minds deserves an audience because it allows readers the privilege of immersion in examinations of Modernist writing, in witnessing earnest and, at times, witty or humorous exchanges, and in seeing how academic (Kenner) and creative (Davenport) projects arise from chance remarks, are worked out (or abandoned), and, now and then, collaborated on, as with Kenner’s book on Flaubert, Joyce and Beckett, The Stoic Comedians(1962), that features Davenport’s illustrations. Both writers urge or hector the other to read, or write, this or that article or book. Kenner encourages Davenport to do extensive translations of the poetry of a particular Greek lyric poet, and this later became Carmina Archilochi: The Fragments of Archilochos (1964). Both interceded to help the other give paid talks or find university positions. Nancy Gardner Williams, John Williams’s widow, lives in a small bungalow in Pueblo, Colorado, close to the desert. This town near the Rocky Mountains was once known for its steel industry. Nancy, a tall woman who holds herself straight, is attentive and observant, friendly yet somewhat reserved. She is not decisively talkative, but you realize immediately that she and her husband must have been on equal terms. “No bluster, no fashion, no pomp,” as Dan Wakefield once remarked about John Williams. That seems to be true for her as well. Nancy studied English literature at the University of Denver. One of her lecturers was John Williams.

Nancy Gardner Williams, John Williams’s widow, lives in a small bungalow in Pueblo, Colorado, close to the desert. This town near the Rocky Mountains was once known for its steel industry. Nancy, a tall woman who holds herself straight, is attentive and observant, friendly yet somewhat reserved. She is not decisively talkative, but you realize immediately that she and her husband must have been on equal terms. “No bluster, no fashion, no pomp,” as Dan Wakefield once remarked about John Williams. That seems to be true for her as well. Nancy studied English literature at the University of Denver. One of her lecturers was John Williams.