Jay Tolson in The Hedgehog Review:

Who is secular man, and why is he so unhappy?

Who is secular man, and why is he so unhappy?

Those are the questions animating The Unnamable Present, a short but wide-ranging book on the puzzles of late modernity and the ninth volume of Roberto Calasso’s extended commentaries on, among many other related topics, the mythical-religious wellsprings of human civilizations. Chairman of Italy’s distinguished literary house Adelphi Edizione, Calasso is too good a historian to say that Homo saecularis emerged only in recent centuries. The lineaments of the type have existed since Paleolithic times, present as what Calasso calls a “perpetual shadow.” The shadow has been cast by the figure dominating most of the human record, Homo religiosus, defined by the sociologist Mircea Eliade as one who “always believes there is an absolute reality, the sacred, which transcends this world but manifests itself in the world, thereby sanctifying it and making it real.”

What has changed dramatically in recent centuries, Calasso writes, is that “the shadow has been transformed into normal man, who finds himself a solitary, hapless protagonist at the center of the stage.” Unlike the many varieties of Homo religiosus—Calasso mentions Vedic man, born owing four debts, above all those to the Hindu gods—Homo saecularis “owes nothing to anyone,” stands alone, free to do what he wishes “so long as it is lawful.”

More here.

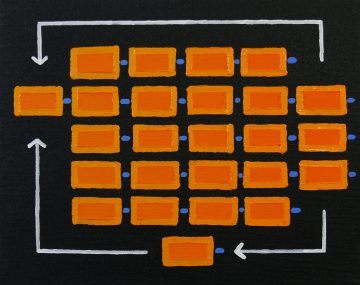

Artificial intelligence is an existence proof of one of the great ideas in human history: that the abstract realm of knowledge, reason, and purpose does not consist of an élan vital or immaterial soul or miraculous powers of neural tissue. Rather, it can be linked to the physical realm of animals and machines via the concepts of information, computation, and control. Knowledge can be explained as patterns in matter or energy that stand in systematic relations with states of the world, with mathematical and logical truths, and with one another. Reasoning can be explained as transformations of that knowledge by physical operations that are designed to preserve those relations. Purpose can be explained as the control of operations to effect changes in the world, guided by discrepancies between its current state and a goal state. Naturally evolved brains are just the most familiar systems that achieve intelligence through information, computation, and control. Humanly designed systems that achieve intelligence vindicate the notion that information processing is sufficient to explain it—the notion that the late Jerry Fodor dubbed the computational theory of mind.

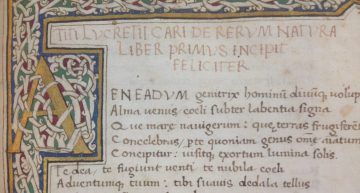

Artificial intelligence is an existence proof of one of the great ideas in human history: that the abstract realm of knowledge, reason, and purpose does not consist of an élan vital or immaterial soul or miraculous powers of neural tissue. Rather, it can be linked to the physical realm of animals and machines via the concepts of information, computation, and control. Knowledge can be explained as patterns in matter or energy that stand in systematic relations with states of the world, with mathematical and logical truths, and with one another. Reasoning can be explained as transformations of that knowledge by physical operations that are designed to preserve those relations. Purpose can be explained as the control of operations to effect changes in the world, guided by discrepancies between its current state and a goal state. Naturally evolved brains are just the most familiar systems that achieve intelligence through information, computation, and control. Humanly designed systems that achieve intelligence vindicate the notion that information processing is sufficient to explain it—the notion that the late Jerry Fodor dubbed the computational theory of mind. ‘The pursuit of Happiness’ is a famous phrase in a famous document, the United States Declaration of Independence (1776). But few know that its author was inspired by an ancient Greek philosopher, Epicurus. Thomas Jefferson considered himself an Epicurean. He probably found the phrase in John Locke, who, like Thomas Hobbes, David Hume and Adam Smith, had also been influenced by Epicurus. Nowadays, educated English-speaking urbanites might call you an epicure if you complain to a waiter about over-salted soup, and stoical if you don’t. In the popular mind, an epicure fine-tunes pleasure, consuming beautifully, while a stoic lives a life of virtue, pleasure sublimated for good. But this doesn’t do justice to Epicurus, who came closest of all the ancient philosophers to understanding the challenges of modern secular life.

‘The pursuit of Happiness’ is a famous phrase in a famous document, the United States Declaration of Independence (1776). But few know that its author was inspired by an ancient Greek philosopher, Epicurus. Thomas Jefferson considered himself an Epicurean. He probably found the phrase in John Locke, who, like Thomas Hobbes, David Hume and Adam Smith, had also been influenced by Epicurus. Nowadays, educated English-speaking urbanites might call you an epicure if you complain to a waiter about over-salted soup, and stoical if you don’t. In the popular mind, an epicure fine-tunes pleasure, consuming beautifully, while a stoic lives a life of virtue, pleasure sublimated for good. But this doesn’t do justice to Epicurus, who came closest of all the ancient philosophers to understanding the challenges of modern secular life. Lodestone, a naturally-occurring iron oxide, was the first persistently magnetic material known to humans. The Han Chinese used it for divining boards 2,200 years ago; ancient Greeks puzzled over why iron was attracted to it; and, Arab merchants placed it in bowls of water to watch the magnet point the way toMecca. In modern times, scientists have used magnets to read and record data on hard drives and form detailed

Lodestone, a naturally-occurring iron oxide, was the first persistently magnetic material known to humans. The Han Chinese used it for divining boards 2,200 years ago; ancient Greeks puzzled over why iron was attracted to it; and, Arab merchants placed it in bowls of water to watch the magnet point the way toMecca. In modern times, scientists have used magnets to read and record data on hard drives and form detailed  Alyssa Battistoni in n+1:

Alyssa Battistoni in n+1: Steven Simon and Jonathan Stevenson in New York Review of Books:

Steven Simon and Jonathan Stevenson in New York Review of Books: John Case in The New Republic:

John Case in The New Republic: T

T I was first alerted to Raymond Geuss’s sour anti-commemoration of Jürgen Habermas’s ninetieth birthday, “

I was first alerted to Raymond Geuss’s sour anti-commemoration of Jürgen Habermas’s ninetieth birthday, “

Gazing at the Moon is an eternal human activity, one of the few things uniting caveman, king and commuter. Each has found something different in that lambent face. For Li Po, a lonely Tang dynasty poet, the Moon was a much-needed drinking buddy. For Holly Golightly, who serenaded it during the “Moon River” scene of “Breakfast at Tiffany’s”, it was a “huckleberry friend” who could whisk her away from her fire escape and her sorrows. By pretending to control a well-timed lunar eclipe, Columbus recruited it to terrify Native Americans into submission. Mussolini superstitiously feared sleeping in its light, and hid from it behind tightly drawn blinds. It would be a challenge for any museum to chronicle the long, complicated relationship humanity has with the Moon, but the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London has done it. For the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon landing, the museum has placed relics from those nine remarkable days in July 1969 alongside cuneiform tablets, Ottoman pocket lunar-calendars, giant Victorian telescopes and instruments designed for India’s first lunar probe in 2008. This impressive exhibition tells the history of humanity’s fascination with this celestial body and looks to the future, as humans attempt once again to return to the Moon.

Gazing at the Moon is an eternal human activity, one of the few things uniting caveman, king and commuter. Each has found something different in that lambent face. For Li Po, a lonely Tang dynasty poet, the Moon was a much-needed drinking buddy. For Holly Golightly, who serenaded it during the “Moon River” scene of “Breakfast at Tiffany’s”, it was a “huckleberry friend” who could whisk her away from her fire escape and her sorrows. By pretending to control a well-timed lunar eclipe, Columbus recruited it to terrify Native Americans into submission. Mussolini superstitiously feared sleeping in its light, and hid from it behind tightly drawn blinds. It would be a challenge for any museum to chronicle the long, complicated relationship humanity has with the Moon, but the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London has done it. For the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon landing, the museum has placed relics from those nine remarkable days in July 1969 alongside cuneiform tablets, Ottoman pocket lunar-calendars, giant Victorian telescopes and instruments designed for India’s first lunar probe in 2008. This impressive exhibition tells the history of humanity’s fascination with this celestial body and looks to the future, as humans attempt once again to return to the Moon. In the early days of the run-up to the 2016 election, I was just beginning to prepare a class on whiteness to teach at Yale University, where I had been newly hired. Over the years, I had come to realize that I often did not share historical knowledge with the persons to whom I was speaking. “What’s redlining?” someone would ask. “George Washington freed his slaves?” someone else would inquire. But as I listened to Donald Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric during the campaign that spring, the class took on a new dimension. Would my students understand the long history that informed a comment like one Trump made when he announced his presidential candidacy? “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best,” he said. “They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.” When I heard those words, I wanted my students to track immigration laws in the United States. Would they connect the treatment of the undocumented with the treatment of Irish, Italian and Asian people over the centuries?

In the early days of the run-up to the 2016 election, I was just beginning to prepare a class on whiteness to teach at Yale University, where I had been newly hired. Over the years, I had come to realize that I often did not share historical knowledge with the persons to whom I was speaking. “What’s redlining?” someone would ask. “George Washington freed his slaves?” someone else would inquire. But as I listened to Donald Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric during the campaign that spring, the class took on a new dimension. Would my students understand the long history that informed a comment like one Trump made when he announced his presidential candidacy? “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best,” he said. “They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.” When I heard those words, I wanted my students to track immigration laws in the United States. Would they connect the treatment of the undocumented with the treatment of Irish, Italian and Asian people over the centuries? Walter Gropius was fond of making claims about The Bauhaus like the following: “Our guiding principle was that design is neither an intellectual nor a material affair, but simply an integral part of the stuff of life, necessary for everyone in a civilized society.” Idealistic and vague, perhaps to a fault, but one gets the point. Bauhaus design was never intended to be alienating. It was supposed to be the opposite. It was supposed to preserve the relative “health” of the craft traditions while marching boldly into a new era. It was supposed to help cure the potential wounds of modern life, wounds caused, initially, by the industrial revolution and its jarring impact on everything from the natural landscape to the material and design of our cutlery. Anti-alienation was really the one guiding intuition behind The Bauhaus as a school and then, more amorphously, as a general approach to architecture and design.

Walter Gropius was fond of making claims about The Bauhaus like the following: “Our guiding principle was that design is neither an intellectual nor a material affair, but simply an integral part of the stuff of life, necessary for everyone in a civilized society.” Idealistic and vague, perhaps to a fault, but one gets the point. Bauhaus design was never intended to be alienating. It was supposed to be the opposite. It was supposed to preserve the relative “health” of the craft traditions while marching boldly into a new era. It was supposed to help cure the potential wounds of modern life, wounds caused, initially, by the industrial revolution and its jarring impact on everything from the natural landscape to the material and design of our cutlery. Anti-alienation was really the one guiding intuition behind The Bauhaus as a school and then, more amorphously, as a general approach to architecture and design.

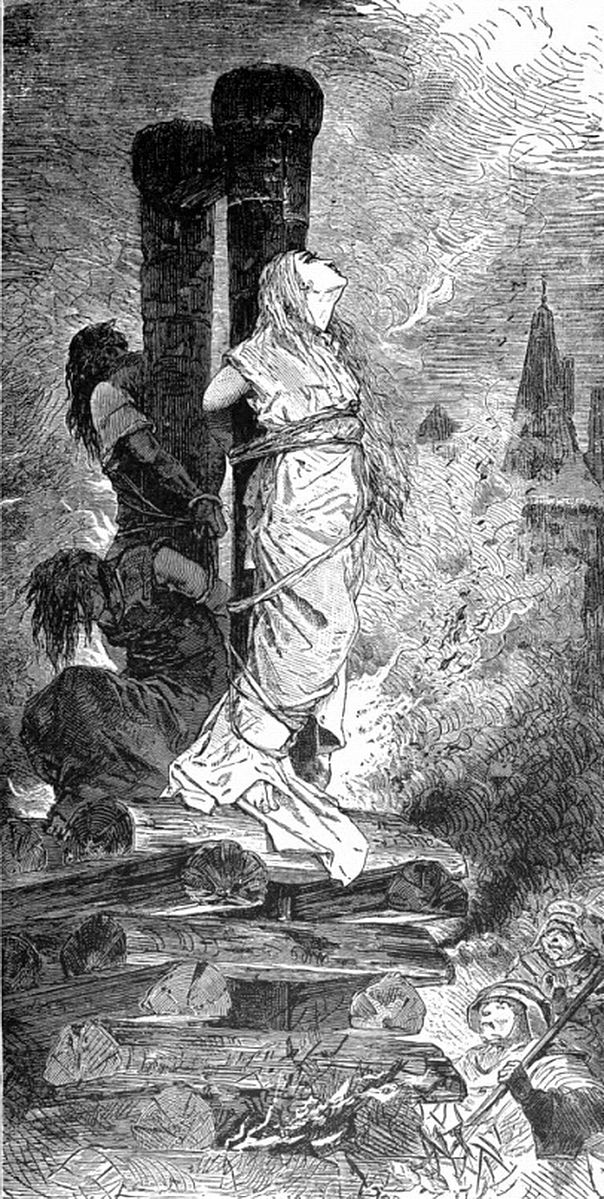

The theory of Darwinian cultural evolution is gaining currency in many parts of the socio-cultural sciences, but it remains contentious. Critics claim that the theory is either fundamentally mistaken or boils down to a fancy re-description of things we knew all along. We will argue that cultural Darwinism can indeed resolve long-standing socio-cultural puzzles; this is demonstrated through a cultural Darwinian analysis of the European witch persecutions. Two central and unresolved questions concerning witch-hunts will be addressed. From the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries, a remarkable and highly specific concept of witchcraft was taking shape in Europe. The first question is: who constructed it? With hindsight, we can see that the concept contains many elements that appear to be intelligently designed to ensure the continuation of witch persecutions, such as the witches’ sabbat, the diabolical pact, nightly flight, and torture as a means of interrogation. The second question is: why did beliefs in witchcraft and witch-hunts persist and disseminate, despite the fact that, as many historians have concluded, no one appears to have substantially benefited from them? Historians have convincingly argued that witch-hunts were not inspired by some hidden agenda; persecutors genuinely believed in the threat of witchcraft to their communities. We propose that the apparent ‘design’ exhibited by concepts of witchcraft resulted from a Darwinian process of evolution, in which cultural variants that accidentally enhanced the reproduction of the witch-hunts were selected and accumulated. We argue that witch persecutions form a prime example of a ‘viral’ socio-cultural phenomenon that reproduces ‘selfishly’, even harming the interests of its human hosts.

The theory of Darwinian cultural evolution is gaining currency in many parts of the socio-cultural sciences, but it remains contentious. Critics claim that the theory is either fundamentally mistaken or boils down to a fancy re-description of things we knew all along. We will argue that cultural Darwinism can indeed resolve long-standing socio-cultural puzzles; this is demonstrated through a cultural Darwinian analysis of the European witch persecutions. Two central and unresolved questions concerning witch-hunts will be addressed. From the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries, a remarkable and highly specific concept of witchcraft was taking shape in Europe. The first question is: who constructed it? With hindsight, we can see that the concept contains many elements that appear to be intelligently designed to ensure the continuation of witch persecutions, such as the witches’ sabbat, the diabolical pact, nightly flight, and torture as a means of interrogation. The second question is: why did beliefs in witchcraft and witch-hunts persist and disseminate, despite the fact that, as many historians have concluded, no one appears to have substantially benefited from them? Historians have convincingly argued that witch-hunts were not inspired by some hidden agenda; persecutors genuinely believed in the threat of witchcraft to their communities. We propose that the apparent ‘design’ exhibited by concepts of witchcraft resulted from a Darwinian process of evolution, in which cultural variants that accidentally enhanced the reproduction of the witch-hunts were selected and accumulated. We argue that witch persecutions form a prime example of a ‘viral’ socio-cultural phenomenon that reproduces ‘selfishly’, even harming the interests of its human hosts.