Shelly Fan in Singularity Hub:

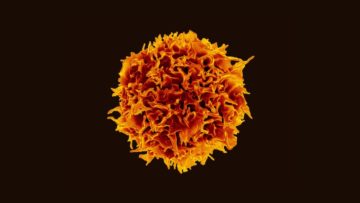

Bacteria may seem like a strange ally in the battle against cancer.

Bacteria may seem like a strange ally in the battle against cancer.

But in a new study, genetically engineered bacteria were part of a tag-team therapy to shrink tumors. In mice with blood, breast, or colon cancer, the bacteria acted as homing beacons for their partners—modified T cells—as the two sought out and destroyed tumor cells. CAR T—the name for therapies using these cancer-destroying T cells—is a transformative approach. First approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for a type of deadly leukemia in 2017, there are now six treatments available for multiple types of blood cancers. Dubbed a “living drug” by pioneer researcher Dr. Carl June at University of Pennsylvania, CAR T is beginning to take on autoimmune diseases, heart injuries, and liver problems. It is also poised to wipe out senescent “zombie cells” linked to age-related diseases and fight off HIV and other viral infections.

Despite its promise, however, CAR T falters when pitted against solid tumors—which make up roughly 90 percent of all cancers. “Each type of tumor has its own little ways of evading the immune system,” said June previously in Penn Medicine News. “So there won’t be one silver-bullet CAR T therapy that targets all types of tumors.” Surprisingly, bacteria may cause June to reconsider—the new approach has potential as a universal treatment for all sorts of solid tumors. When given to mice, the engineered bugs dug deep into the cores of tumors and readily secreted a synthetic “tag” to draw in nearby CAR T soldiers. The molecular tag only sticks to the regions immediately surrounding a tumor and spares healthy cells from CAR T attacks. The engineered bacteria could also, in theory, infiltrate other types of solid tumors, including “sneaky” ones difficult to target with conventional therapies. Together, the new method called ProCAR—probiotic-guided CAR T cells—combines bacteria and T cells into a cancer-fighting powerhouse.

More here.

“What’s that thing with the fire?” a woman from the table behind me asks, tugging on the vents of my tuxedo jacket and gesturing toward the dessert I just finished flambéing. I’m tempted to lie and tell her we just sold out, but instead I explain the Bananas Foster — caramelized bananas flamed with dark rum over house-made banana-buttermilk ice cream — the restaurant’s most popular dessert. But she isn’t listening. I can already sense her plans to cast me as the lead in her TikTok video or the poster child for her “en fuego” meme. “Oh my God, I hate bananas,” she says, turning toward her tablemates, “but we should totally order it anyway!” They haven’t even finished their appetizers.

“What’s that thing with the fire?” a woman from the table behind me asks, tugging on the vents of my tuxedo jacket and gesturing toward the dessert I just finished flambéing. I’m tempted to lie and tell her we just sold out, but instead I explain the Bananas Foster — caramelized bananas flamed with dark rum over house-made banana-buttermilk ice cream — the restaurant’s most popular dessert. But she isn’t listening. I can already sense her plans to cast me as the lead in her TikTok video or the poster child for her “en fuego” meme. “Oh my God, I hate bananas,” she says, turning toward her tablemates, “but we should totally order it anyway!” They haven’t even finished their appetizers.

If you’re new to my work, I’m a self-taught researcher, driven to learn through fortunate access to high sample sizes and sheer curiosity. As of this writing, over 700,000 people have responded to my

If you’re new to my work, I’m a self-taught researcher, driven to learn through fortunate access to high sample sizes and sheer curiosity. As of this writing, over 700,000 people have responded to my

‘That’s our mountain,’ a wordy Neapolitan told Hester Piozzi, ‘which throws up money for us, by calling foreigners to see the extraordinary effects of so surprising a phenomenon.’ The hermits were only one part of a flourishing and lucrative Vesuvius service industry that visitors encountered as they began their ascents. As Brewer says, what the industry was ‘selling was a sublime experience’. Making your own way up the mountain to see the extraordinary effects was perilous, but help was at hand. Your first encounter upon arrival would be with a disorganised horde of vociferous guides, all offering their services. The spectacle seems to have been distinctly off-putting: the poet Shelley, generally a friend of humanity, thought these particular humans ‘degraded, disgusting & odious’. Degraded or not, some guides became celebrities: Salvatore Madonna (‘il capo cicerone’) was well-known for his narrative skills and general charm, as well as for his knowledge of the territory, and he even appeared in guidebooks as a colourful feature of the scene to be looked out for. Madonna seems to have been a professional type, but untrustworthy guides were not uncommon.

‘That’s our mountain,’ a wordy Neapolitan told Hester Piozzi, ‘which throws up money for us, by calling foreigners to see the extraordinary effects of so surprising a phenomenon.’ The hermits were only one part of a flourishing and lucrative Vesuvius service industry that visitors encountered as they began their ascents. As Brewer says, what the industry was ‘selling was a sublime experience’. Making your own way up the mountain to see the extraordinary effects was perilous, but help was at hand. Your first encounter upon arrival would be with a disorganised horde of vociferous guides, all offering their services. The spectacle seems to have been distinctly off-putting: the poet Shelley, generally a friend of humanity, thought these particular humans ‘degraded, disgusting & odious’. Degraded or not, some guides became celebrities: Salvatore Madonna (‘il capo cicerone’) was well-known for his narrative skills and general charm, as well as for his knowledge of the territory, and he even appeared in guidebooks as a colourful feature of the scene to be looked out for. Madonna seems to have been a professional type, but untrustworthy guides were not uncommon. Aviation produces about

Aviation produces about Staring into the mirror, on a Tuesday morning, you decide that your self needs all the help it can get. But where to turn? You were reading James Clear’s “

Staring into the mirror, on a Tuesday morning, you decide that your self needs all the help it can get. But where to turn? You were reading James Clear’s “ Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) means many different things to different people, but the most important parts of it have already been achieved by the

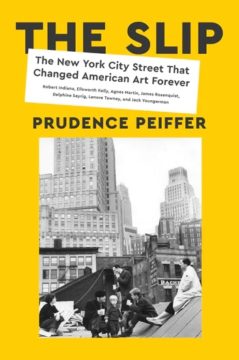

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) means many different things to different people, but the most important parts of it have already been achieved by the  BETWEEN 1956 AND 1967, the Coenties Slip on the lower tip of Manhattan was home to a group of artists who had moved to the city with grand ambitions for their work and little money to their names. In those lean years, before they were canonized, Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, Lenore Tawney, Jack Youngerman, and Delphine Seyrig all took up residence in this “down downtown,” on a dead-end street on the East River where they nested themselves among fishing ships and sailors, the changing tides and unremitting grime, living at a remove from the New York City art world. Here on “the Slip”—a commercial dock designed for transience and exchange—they lived in cheap and drafty lofts, nurturing intuitions and ideas into radical practices, producing bodies of work that would, in the end, be very much a part of the zeitgeist.

BETWEEN 1956 AND 1967, the Coenties Slip on the lower tip of Manhattan was home to a group of artists who had moved to the city with grand ambitions for their work and little money to their names. In those lean years, before they were canonized, Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, Lenore Tawney, Jack Youngerman, and Delphine Seyrig all took up residence in this “down downtown,” on a dead-end street on the East River where they nested themselves among fishing ships and sailors, the changing tides and unremitting grime, living at a remove from the New York City art world. Here on “the Slip”—a commercial dock designed for transience and exchange—they lived in cheap and drafty lofts, nurturing intuitions and ideas into radical practices, producing bodies of work that would, in the end, be very much a part of the zeitgeist. Noisy. Hysterical. Brash. The textual version of junk food. The selfie of grammar. The exclamation point attracts enormous (and undue) amounts of flak for its unabashed claim to presence in the name of emotion which some unkind souls interpret as egotistical attention-seeking. We’ve grown suspicious of feelings, particularly the big ones needing the eruption of a ! to relieve ourselves. This trend started sometime around 1900 when modernity began to mean functionality and clean straight lines (witness the sensible boxes of a Bauhaus building), rather than the “extra” mood of Victorian sensitivity or frilly playful Renaissance decorations.

Noisy. Hysterical. Brash. The textual version of junk food. The selfie of grammar. The exclamation point attracts enormous (and undue) amounts of flak for its unabashed claim to presence in the name of emotion which some unkind souls interpret as egotistical attention-seeking. We’ve grown suspicious of feelings, particularly the big ones needing the eruption of a ! to relieve ourselves. This trend started sometime around 1900 when modernity began to mean functionality and clean straight lines (witness the sensible boxes of a Bauhaus building), rather than the “extra” mood of Victorian sensitivity or frilly playful Renaissance decorations. David Deutsch is one of the most creative scientific thinkers working today, who has as a goal to understand and explain the natural world as best we can. He was a pioneer in quantum computing, and has long been an advocate of the Everett interpretation of quantum theory. He is also the inventor of

David Deutsch is one of the most creative scientific thinkers working today, who has as a goal to understand and explain the natural world as best we can. He was a pioneer in quantum computing, and has long been an advocate of the Everett interpretation of quantum theory. He is also the inventor of  What happens when lonely men, embittered by a sense of failure in the sexual marketplace, find each other and form communities on the internet? The result can be deadly.

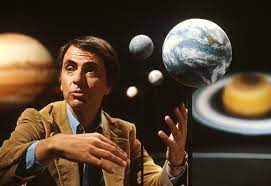

What happens when lonely men, embittered by a sense of failure in the sexual marketplace, find each other and form communities on the internet? The result can be deadly. Early in 1993, a manuscript landed in the Nature offices announcing the results of an unusual — even audacious — experiment. The investigators, led by planetary scientist and broadcaster Carl Sagan, had searched for evidence of life on Earth that could be detected from space. The results, published 30 years ago this week, were “strongly suggestive” that the planet did indeed host life. “These observations constitute a control experiment for the search for extraterrestrial life by modern interplanetary spacecraft,” the team wrote (

Early in 1993, a manuscript landed in the Nature offices announcing the results of an unusual — even audacious — experiment. The investigators, led by planetary scientist and broadcaster Carl Sagan, had searched for evidence of life on Earth that could be detected from space. The results, published 30 years ago this week, were “strongly suggestive” that the planet did indeed host life. “These observations constitute a control experiment for the search for extraterrestrial life by modern interplanetary spacecraft,” the team wrote (