Category: Archives

Global Extreme Poverty

Max Roser and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina over at Our World in Data:

The most important conclusion from the evidence presented in this entry is that extreme poverty, as measured by consumption, has been going down around the world in the last two centuries. But why should we care? Is it not the case that poor people might have less consumption but enjoy their lives just as much—or even more—than people with much higher consumption levels?

One way to find out is to simply ask. Subjective views are an important way of measuring welfare.

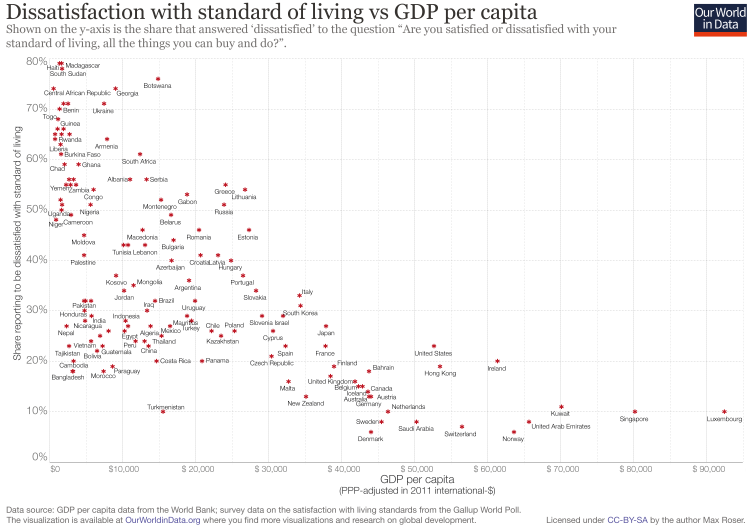

This is what the Gallup Organization did. The Gallup World Poll asked people around the world what they thought about their standard of living—not only about their income. The following chart compares the answers of people in different countries with the average income in those countries. It shows that, broadly speaking, people living in poorer countries tend to be less satisfied with their living standards.

Dissatisfaction with standard of living vs GDP per capita

This suggests that economic prosperity is not a vain, unimportant goal but rather a means for a better life. The correlation between rising incomes and higher self-reported life satisfaction is shown in our entry on happiness.

This is more than a technical point about how to measure welfare. It is an assertion that matters for how we understand and interpret development.

First, the smooth relationship between income and subjective well-being highlights the difficulties that arise from using a fixed threshold above which people are abruptly considered to be non-poor. In reality, subjective well-being does not suddenly improve above any given poverty line. This makes using a fixed poverty line to define destitution as a binary ‘yes/no’ problematic. Therefore, while the International Poverty Line is useful for understanding the changes in living conditions of the very poorest of the world, we must also take into account higher poverty lines reflecting the fact that living conditions at higher thresholds can still be destitute.

And second, the fact that people with very low incomes tend to be dissatisfied with their living standards shows that it would be incorrect to take a romantic view on what ‘life in poverty’ is like. As the data shows, there is just no empirical evidence that would suggest that living with very low consumption levels is romantic.

More here.

Chocolate Can Protect Our Brains

Sheherzad Preisler in OliveOilTimes:

A research team based at Italy’s University of L’Aquila have published a new study that says cocoa beans contain high concentrations of flavanols, which are naturally-occurring compounds that can protect our brains. The team, whose findings were published in Frontiers in Nutrition, reviewed current scientific literature in the hopes of finding out if the sustained concentrations of cocoa flavanols found in regular chocolate-eaters had any effect on the brain. What the team found was a breadth of trials in which participants that regularly consumed chocolate processed visual information better and had improved “working memories.” Furthermore, women who consumed cocoa after a sleepless night saw a reversal of negative side effects that come from sleep deprivation, such as compromised task performance. This could be great for those who work particularly stressful jobs that compromise one’s sleep as well as those with recurring sleep issues.

Diets such as the Mediterranean diet encourage the consumption of chocolate in moderation, and this study further supports such suggestions. However, the results should be taken with a grain of salt: the positive effects from cocoa flavanols differed based on the variety of the mental tests. For young adults who were in good health, they needed a very intense cognition test to expose cocoa’s immediate benefits. Most research on this subject to date generally involves elderly populations who have consumed cocoa flavanols from anywhere between five days and three months. For this population, daily consumption of cocoa flavanols had the most positive profound effect on their cognition, improving their verbal fluency, processing speed, and attention span. The benefits were most noticeable in subjects whose cognitive abilities had minor damage or whose memories had previously begun to decline.

More here.

Tuesday, July 25, 2017

Two people drive drunk at night: one kills a pedestrian, one doesn’t. Does the unlucky killer deserve more blame or not?

Robert J Hartman in Aeon:

There is a contradiction in our ordinary ideas about moral responsibility. Let’s explore it by considering two examples. Killer, our first character, is at a party and drives home drunk. At a certain point in her journey, she swerves, hits the curb, and kills a pedestrian who was on the curb. Merely Reckless, our second character, is in every way exactly like Killer but, when she swerves and hits a curb, she kills no one. There wasn’t a pedestrian on the curb for her to kill. The difference between Killer and Merely Reckless is a matter of luck.

Does Killer deserve more blame – that is, resentment and indignation – than Merely Reckless? Or, do Killer and Merely Reckless deserve the same degree of blame? We feel a pull to answer ‘yes’ to both questions. Let’s consider why.

On the one hand, we believe that Killer deserves more blame than Merely Reckless, because it’s only Killer who causes the death of a pedestrian. Plausibly, a person can deserve extra blame for a bad result of her action that she reasonably could have been expected to foresee, and causing the death of a pedestrian by driving drunk is that kind of bad consequence. So, even though they deserve an equal degree of blame for their callous and reckless driving, Killer deserves more blame overall, because only Killer’s foreseeable moral risk turns out badly.

On the other hand, we believe that Killer and Merely Reckless must deserve the same degree of blame, because luck is the only difference between them, and luck, most of us think, cannot affect the praise and blame a person deserves. It would be unfair for Killer to deserve more blame due merely to what happened to her, because moral judgment is about a person and not what happens to her. So, they must deserve the same degree of blame.

In summary, our commonsense ideas about moral responsibility imply the contradiction that Killer and Merely Reckless do and do not deserve the same amount of resentment and indignation. More generally, our commonsense ideas about moral responsibility have the paradoxical implication that luck in results can and cannot affect how much praise and blame a person deserves.

Nevertheless, the vexation runs deeper. Luck clearly affects the results of actions but, less obviously, as I’ll demonstrate, luck can also affect actions themselves.

More here.

10,000 Hours With Claude Shannon: How A Genius Thinks, Works, and Lives

Rob Goodman and Jimmy Soni in The Mission:

For the last five years, we lived with one of the most brilliant people on the planet.

Sort of.

See, we just published the biography of Dr. Claude Shannon. He’s the most important genius you’ve never heard of, a man whose intellect was on par with Albert Einstein and Isaac Newton.

We spent five years with him. It’s not an exaggeration to say that, during that period, we spent more time with the deceased Claude Shannon than we have with many of our living friends. He became something like the roommate in the spare bedroom of our minds, the guy who was always hanging around and occupying our head space.

Yes, we were the ones telling his story, but in telling it, he affected us, too. Geniuses have a unique way of engaging with the world, and if you spend enough time examining their habits, you discover the behaviors behind their brilliance. Whether or not we intended it to, understanding Claude Shannon’s life gave us lessons on how to better live our own.

That’s what follows in this essay. It’s the good stuff our roommate left behind.

More here.

Sean Carroll: Extracting the Universe from the Wave Function

Video length: 38:04

‘Make It So’: ‘Star Trek’ and Its Debt to Revolutionary Socialism

A.M. Gittlitz in the NYT:

Gorky was a fan of the Cosmism of Nikolai Fyodorov and Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, a scientific and mystical philosophy proposing space exploration and human immortality. When Lenin died four years after meeting with Wells, the futurist poet Vladimir Mayakovsky’s line “Lenin Lived, Lenin Lives, Lenin Will Live Forever!” became not only a state slogan, but also a scientific goal. These Biocosmist-Immortalists, as they were known, believed that socialist scientists, freed from the constraints of the capitalist profit motive, would discover how to abolish death and bring back their comrades. Lenin’s corpse remains preserved for the occasion.

Bogdanov died in the course of his blood-sharing experiments, and other futurist dreams were sidelined by the industrial and militarist priorities that led up to World War II. In the postwar period, however, scientists inspired by Cosmism launched Sputnik. The satellite’s faint blinking in the night sky signaled an era of immense human potential to escape all limitations natural and political, with the equal probability of destroying everything in a matter of hours.

Feeding on this tension, science fiction and futurism entered their “golden age” by the 1950s and ’60s, both predicting the bright future that would replace the Cold War. Technological advances would automate society; the necessity of work would fade away. Industrial wealth would be distributed as a universal basic income, and an age of leisure and vitality would follow. Humans would continue to voyage into space, creating off-Earth colonies and perhaps making new, extraterrestrial friends in the process. In a rare 1966 collaboration across the Iron Curtain, the astronomer Carl Sagan co-wrote “Intelligent Life in the Universe” with Iosif Shklovosky. This work of astrobiological optimism proposed that humans attempt to contact their galactic neighbors.

More here.

criticizing rorty’s critics

María Pía Lara at the LARB:

Why then was Rorty ever considered a relativist? Here is one answer: Throughout his career, Rorty was against prescriptions, against thinking that he could provide us with universal foundations or discoveries. Instead, he sought to recover the successes of labor unions and other leftist organizations. This included younger leftists, who engaged in social disobedience, after seeing anticommunism being used as an excuse to destroy innocent people in southeast Asia. Rorty maintained that the killing of civilians and soldiers in Vietnam was morally indefensible and that the war had ended up degrading the morals of the United States. Moreover, he claimed, that the political effectiveness of the antiwar movements would give hope to future generations.

Rorty often cited the contributions of pragmatists like John Dewey or William James, whose essays he compared to Walt Whitman’s poetry, because they were aware that it is in the making of something — a movement, a concept, a turn of a phrase to describe our world — rather than in finding “truths,” that we articulate social and political changes for the better. He observed that both writers believed that “democracy” and “the project of America” was “a political construction” and could be taken as “convertible,” that is, “equivalent” terms.

more here.

What does Jane Austen mean to you?

Geoff Dyer and many others at the TLS:

We did Emma for A Level, so it was one of the first serious novels I ever read. In a sense, then, Jane Austen is literature to me. She was not just one of the first novelists I read but also the oldest, i.e. earliest. You can start further back, of course, but romping through Tom Jones feels like a bit of a waste of olde time in the way that Persuasion never does. I associate reading Austen with a consciousness of the gap between my limited life experience – swilling beer, basically – and the expanded grasp of the psychological subtleties and nuances of situations and relationships that her books gradually revealed. But I’m conscious also of a different kind of gap: that between the riches afforded by the novels and the tedium of the criticism served up alongside them. Macmillan Casebooks – anthologies of critical essays – were the default educational tools even though most of the pieces in the one on Emma are complete dross. The process whereby “doing English” morphed into “doing criticism” began with Austen and continued all the way through university. Was this a purposeful deterrent? George Steiner is right: the best critical essay on Jane Austen is Middlemarch.

Whereas my head is full of Shakespeare, only a few lines from Austen have stayed with me – the very ones, predictably, that had us smirking at school: “Anne had always found such a style of intercourse highly imprudent” (Persuasion), or Mr Elton “making violent love” to Emma in a carriage.

more here.

was Billy Budd black?

Philip Hoare at The New Statesman:

Was Billy Budd, the Handsome Sailor at the heart of the book, black? Scholars such as John Bryant believe that there is internal evidence in the manuscript of the book – found in a bread tin after Melville’s death in 1891 and not published until 1924 – that the author had played with the idea of making his hero a man of African heritage. Billy is loved by all the crew and is described as blond and blue-eyed later in the story. Yet the sensuous descriptions of the Liverpool sailor and the Greenwich veteran elide to create a counterfactual version in which Billy becomes a black star at the centre of his constellation of shipmates.

Indeed, some critics – most notably, Cassandra Pybus at the University of Sydney – have suggested that another 19th-century anti-hero was a person of colour. In Wuthering Heights, published in 1847, two years before Melville’s visit, Heathcliff is described as a “regular black”, an orphan found in the Liverpool docks – an intriguing notion explored in Andrea Arnold’s brilliant 2011 film adaptation.

Melville witnessed great changes in the fortunes of black Americans. Moby-Dick is an allegory of the struggle against slavery in the run-up to the American Civil War; the Melville scholar Robert K Wallace believes that the writer heard the fugitive slave-turned-emancipationist Frederick Douglass speak in the 1840s and that they may have even met.

more here.

The New Science of Daydreaming

Michael Harris in Discover:

“I’m sorry, Julie, but it’s just a fact — people are terrified of being in their heads,” I say. “I read this study where subjects chose to give themselves electric shocks rather than be alone with their own thoughts.” It’s the summer of 2015 and the University of British Columbia’s half-vacated grounds droop with bloom. Julie — an old friend I’ve run into on campus — gives me a skeptical side-eye and says she’s perfectly capable of being alone with her thoughts. Proving her point, she wanders out of the rose garden in search of caffeine. I glower at the plants. The study was a real one. It was published in 2014 in Science and was authored by University of Virginia professor Timothy D. Wilson and his team. Their research revealed that, left in our own company, most of us start to lose it after six to 15 minutes. The shocks are preferable, despite the pain, because anything — anything — is better than what the human brain starts getting up to when left to its own devices.

Or so we assume.

What the brain in fact gets up to in the absence of antagonizing external stimuli (buzzing phones, chirping people) is daydreaming. I am purposefully making it sound benign. Daydreaming is such a soft term. And yet it refers to a state of mind that most of us — myself included — have learned to suppress like a dirty thought. Perhaps we suppress it out of fear that daydreaming is related to the sin of idle hands. From at least medieval times onward, there’s been a steady campaign against idleness, that instigator of evil. Today, in the spaces where I used to daydream, those interstitial moments on a bus, in the shower, or out on a walk, I’m hounded by a guilt and quiet desperation — a panicked need to block my mind from wandering too long on its own. The mind must be put to use.

More here.

England’s Mental Health Experiment: It makes economic sense

Benedict Carey in The New York Times:

England is in the midst of a unique national experiment, the world’s most ambitious effort to treat depression, anxiety and other common mental illnesses.

The rapidly growing initiative, which has gotten little publicity outside the country, offers virtually open-ended talk therapy free of charge at clinics throughout the country: in remote farming villages, industrial suburbs, isolated immigrant communities and high-end enclaves. The goal is to eventually create a system of primary care for mental health not just for England but for all of Britain. At a time when many nations are debating large-scale reforms to mental health care, researchers and policy makers are looking hard at England’s experience, sizing up both its popularity and its limitations. Mental health care systems vary widely across the Western world, but none have gone nearly so far to provide open-ended access to talk therapies backed by hard evidence. Experts say the English program is the first broad real-world test of treatments that have been studied mostly in carefully controlled lab conditions. The demand in the first several years has been so strong it has strained the program’s resources. According to the latest figures, the program now screens nearly a million people a year, and the number of adults in England who have recently received some mental health treatment has jumped to one in three from one in four and is expected to continue to grow. Mental health professionals also say the program has gone a long way to shrink the stigma of psychotherapy in a nation culturally steeped in stoicism. “You now actually hear young people say, ‘I might go and get some therapy for this,’” said Dr. Tim Kendall, the clinical director for mental health for the National Health Service. “You’d never, ever hear people in this country say that out in public before.”

The enormous amount of data collected through the program has shown the importance of a quick response after a person’s initial call and of a triage-like screening system in deciding a course of treatment. It will potentially help researchers and policy makers around the world to determine which reforms can work — and which most likely will not. “It’s not just that they’re enhancing access to care, but that they’re being accountable for the care that’s delivered,” said Karen Cohen, chief executive of the Canadian Psychological Association, which has been advocating a similar system in Canada. “That is what makes the effort so innovative and extraordinary.”

More here.

Monday, July 24, 2017

CATSPEAK

by Brooks Riley

Sunday, July 23, 2017

In “Arbitrary Stupid Goal”, Conjuring a Lost New York City

Julia Felsenthal in Vogue:

“There are roughly three New Yorks,” E.B. White once wrote. “There is, first, the New York of the man or woman who was born here, who takes the city for granted and accepts its size and its turbulence as natural and inevitable. Second, there is the New York of the commuter—the city that is devoured by locusts each day and spat out each night. Third, there is the New York of the person who was born somewhere else and came to New York in quest of something.”

For White, that last New York, “the city of final destination, the city that is a goal,” was the greatest of all. The illustrator, graphic designer, cook, writer, and born-and-bred New Yorker Tamara Shopsin quotes this passage—drawn from White’s essay Here is New York—in her new memoir, Arbitrary Stupid Goal. Her book, among many other things, traces its author’s unconventional childhood, growing up in a one-bedroom apartment on Morton Street with four siblings and her parents, Kenny and Eve Shopsin, the eccentric proprietors of their eponymous, legendarily idiosyncratic West Village grocery-store-turned-eatery. (If you’re wondering about logistics, Shopsin writes that she slept in a bookshelf.)

Their business, Shopsin’s, or for those in the know, “The Store,” was housed for roughly three decades in a storefront on the corner of Bedford and Morton. In 2002, forced out by rapidly rising rents, Shopsin’s moved a couple blocks over to Carmine Street; then, a few years later, the restaurant moved again to its current home in Essex Market on the Lower East Side. Eve passed away in the mid-aughts. Kenny, The Store’s burly, famously bellicose chef, still mans the kitchen with his son Zack.

White’s essay, writes Shopsin in her memoir, is “written with so much love and grace its words become fact.” Still, she quibbles with his conclusion. “The third New Yorker, the non-native, takes a thing for granted too,” she asserts. “The third New Yorker knows they can live somewhere else. They have done it once, deep down if need be they can do it again.”

More here.

Quantum teleportation is even weirder than you think

Philip Ball in Nature:

A BBC headline last week, ‘First object teleported to Earth’s orbit’, has to be one of the most fantastical you’ll see this year. For once, it seems the future that science fiction promised has arrived! Or has it?

The article was talking about reports by Chinese scientists that they had transmitted the quantum state of a photon on Earth to another photon on a satellite in low Earth orbit, some 1,400 kilometres away1. That kind of transmission — first demonstrated in a laboratory 20 years ago2 — is known as quantum teleportation.

It’s a label that can mislead the unwary, as the BBC headline demonstrates. A write-up of the work in Discover reports that the scientists “have successfully transmitted quantum entangled particles” — only to clarify, confusingly, that “unlike science fiction teleportation devices, nothing physical is being transported”.

But wait: didn’t someone once say information is physical? That was physicist Rolf Landauer3, a pioneer of information theory. So if you send nothing physical, how can you transmit anything at all from A to B?

This is one of the deep issues that quantum physicists and philosophers still argue about. We can debate whether ‘quantum teleportation’ as a term is a catchy way of conveying a scientific idea, or a misleading bit of hype. But the real question — what, exactly, is transmitted during quantum teleportation, and how — touches on issues much more profound.

More here.

To Kolkata, From Baghdadi Jews, With Love

Jael Silliman in The Wire:

Crisp on the outside, soft inside, the golden brown, whole fried potatoes were brought piping hot to the dining table. My father, David, urged his guests to abandon even trying to tackle these “jumping potatoes” with their forks and knives. “Just sink your teeth in them!” He had remarked cheerfully. We did and enjoyed the crackle in our mouths that slowly yielded to the soft, oozing centre melting on our tongues. Aloo makallah was definitely the star attraction of Baghdadi Jewish meals and a Calcutta specialty.

My father’s ancestor, Shalome Obadiah Ha Cohen, was the first Jew to come from Aleppo, Syria in the late eighteenth for trade in Calcutta and make it his home. Yet, our Middle Eastern community is loosely called ‘Baghdadi’ as we followed the liturgy of Baghdad, a centre of Jewish learning. We Baghdadis flourished in the port cities of ‘Jewish Asia’ that stretched from Baghdad to Shanghai. In Karachi, Bombay, Calcutta, Rangoon, Singapore, Penang, Djakarta, Hong Kong and Shanghai, small enclaves of Jews relied upon one another for religious, financial and social support. Marriages, commercial news, business and family connections welded us into a powerful economic and cultural presence in the East.

In Calcutta, the second city of Empire, we adapted to our new home and shifted from being Judaeo-Arabic to Judaeo-British in our language, as well as shifted in terms of dress and cultural orientation. We lived among Anglo Indian, Parsis, Armenians, Chinese as well as Hindus and Muslims.

More here.

When Cold War philosophy tied rational choice theory to scientific method, it embedded the free-market mindset in US society

John McCumber in Aeon:

The chancellor of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) was worried. It was May 1954, and UCLA had been independent of Berkeley for just two years. Now its Office of Public Information had learned that the Hearst-owned Los Angeles Examiner was preparing one or more articles on communist infiltration at the university. The news was hardly surprising. UCLA, sometimes called the ‘little Red schoolhouse in Westwood’, was considered to be a prime example of communist infiltration of universities in the United States; an article in The Saturday Evening Post in October 1950 had identified it as providing ‘a case history of what has been done at many schools’.

The chancellor, Raymond B Allen, scheduled an interview with a ‘Mr Carrington’ – apparently Richard A Carrington, the paper’s publisher – and solicited some talking points from Andrew Hamilton of the Information Office. They included the following: ‘Through the cooperation of our police department, our faculty and our student body, we have always defeated such [subversive] attempts. We have done this quietly and without fanfare – but most effectively.’ Whether Allen actually used these words or not, his strategy worked. Scribbled on Hamilton’s talking points, in Allen’s handwriting, are the jubilant words ‘All is OK – will tell you.’

Allen’s victory ultimately did him little good. Unlike other UCLA administrators, he is nowhere commemorated on the Westwood campus, having suddenly left office in 1959, after seven years in his post, just ahead of a football scandal. The fact remains that he was UCLA’s first chancellor, the premier academic Red hunter of the Joseph McCarthy era – and one of the most important US philosophers of the mid-20th century.

More here.

Usain Bolt is the fastest sprinter ever in spite of — or because of? — an uneven stride that upends conventional wisdom

Jere Longman in the New York Times:

Usain Bolt of Jamaica appeared on a video screen in a white singlet and black tights, sprinting in slow motion through the final half of a 100-meter race. Each stride covered nine feet, his upper body moving up and down almost imperceptibly, his feet striking the track and rising so rapidly that his heels did not touch the ground.

Bolt is the fastest sprinter in history, the world-record holder at 100 and 200 meters and the only person to win both events at three Olympics. Yet as he approaches his 31st birthday and retirement this summer, scientists are still trying to fully understand how Bolt achieved his unprecedented speed.

Last month, researchers here at Southern Methodist University, among the leading experts on the biomechanics of sprinting, said they found something unexpected during video examination of Bolt’s stride: His right leg appears to strike the track with about 13 percent more peak force than his left leg. And with each stride, his left leg remains on the ground about 14 percent longer than his right leg.

This runs counter to conventional wisdom, based on limited science, that an uneven stride tends to slow a runner down.

More here.

On Being Smaller

Colin Gillis in Avidly:

The other day, as I was returning empty trash cans from the curb in front of our apartment building, the older man who owns the home across the street from my apartment waved to me. “Hi! I don’t think we’ve met.” In fact, we had met, over five years before, when my wife and I first moved in to our apartment, and we had regularly greeted each other since then, or, at least, we had until recently. In the past six months, my appearance has changed dramatically. I lost a lot of weight, almost 100 pounds. After I explained what had happened to my neighbor, he shouted, “Holy shit!” several times in a row. In a way, my neighbor’s introduction was appropriate. This radical change in appearance has made me feel like a new person. My new body can do many things that the old one couldn’t, and my awareness of its expanded capacities imbues the future with possibility. I want to run a marathon, climb mountains, learn to dance—and, for the first time, my body is not an impediment to doing so. But the change isn’t just physical. Losing so much weight means that the world treats me differently in fundamental ways. In addition to physical mass, I am also unburdened from the psychological weight of stigma. As my body changed, its meaning changed with it—for other people and for me.

The world wants my happiness about this transformation to be pure. People who comment on my new appearance tend to describe it with metaphors of evolution or conversion, endowing the adipose tissue I used to carry on my body with moral as well as physiological significance. It seems that my weight was, for many, the physical symptom of a lack of virtue as well as a clear and present danger to my health. This was something that I always knew on an abstract level. Nobody ever accused me of a lack of virtue, the sense of failure, to my face. Now that I’m relatively thin, that’s changed. At my last annual physical, my doctor said, as he was examining my almost naked body, “Your wife must love the new you!” This was not the first time I had considered what effect, if any, the physical transformations wrought by weight loss and vigorous exercise had on my life partner’s perception of me, but it was certainly the first time someone else had baldly stated that she probably found me more attractive now. “She tells me she likes the new me, but she also insists that she liked the old me, too,” I replied, honestly. And added, also honestly, “Of course, one wonders.”

…But there was also something attractive and deeply pleasurable about being—and living—large, about cultivating huge appetites and satisfying them with abandon. Eating piles of calorie rich food and guzzling it down with wine is tremendously fun, and I look back on occasions when I did that with fondness, a hint of jealousy, and with only the slightest regret. And my large body was so powerful! I trained until I could deadlift 420 pounds. The rush of excitement doing this gave me, the sense of accomplishment, the physical pleasure of muscles flush with blood, was a palpable sense of strength that I carried with me, in body and in mind. Removing over thirty percent of my total body mass has entailed losses of pleasures that I once associated with being huge and that remain important for me. These are more than just the pleasures of regular excess in food and drink. I am physically smaller now and less strong than I once was. I may never gain back all of my old strength.

How Breitbart Media’s Disinformation Created the Paranoid, Fact-Averse Nation That Elected Trump

Steven Rosenfeld in AlterNet:

Right-wing media evolved into a hall of mirrors in 2016, when Breitbart displaced Fox News as the key agenda-setting and attack-leading epicenter of a disinformation-filled, paranoid ecosystem promoting Donald Trump and his pro-white America agenda. Breitbart not only led the right’s obsessive, hostile focus on immigrants, it was also the first to attack professional reporting such as the New York Times and Washington Post. Breitbart's disruptive template fueled the political and information universe we now inhabit, where the right dismisses facts and embraces fantasies. There is no corollary dynamic on the left or among pro-Clinton audiences in 2016. The left's news sources, media consumption and patterns of social media-sharing are more open-minded and fact-based and less insular and aggressive. Still, Breitbart’s obsessive focus on fabricating and hyping scandals involving Hillary Clinton (and Jeb Bush early in the primary season) pushed mainstream media to disproportionately cover its agenda.

These observations are among the takeaways of a major study from Columbia Journalism Review that analyzed 1.25 million stories published online between April 2015 and Election Day 2016. While the study affirmed what many analysts have long perceived—that right-wing media and those who consume it inhabit a paranoid and dark parallel universe—it also documented shifts in the right’s media ecosystem; namely, Breitbart supplanting Fox News as the leading purveyor of extreme disinformation. “A right-wing media network anchored around Breitbart [has] developed as a distinct and insulated media system, using social media as a backbone to transmit a hyper-partisan perspective to the world,” CJR wrote. “This pro-Trump media sphere appears to have not only successfully set the agenda for the conservative media sphere, but also strongly influenced the broader media agenda, in particular coverage of Hillary Clinton.”

The CJR report said Americans’ media consuming habits are “asymmetric,” meaning those on the left—progressives and Democrats—rely on more diverse outlets and content, compared to the right.

More here.