by Jerry Cayford

The Google advertising technology trial is a very big deal. While we are waiting for the final decision from Judge Leonie Brinkema of the U.S. District Court for Eastern Virginia, I want to present some thoughts on the least resolved of the case’s many issues, the hard parts the judge will be pondering. Actually, one hard part: trust. But I need to tell you a little about the case to make the trust issue clear. I’ll give a brief introduction, but will refer you for more detail to the daily reports I wrote for Big Tech on Trial (BTOT) last September-October.

The ad tech trial is the third of three cases in which Google was accused of illegal monopolization, all of which Google lost. The first (brought by Epic Games) was for monopolizing the Android app distribution market. The second was for monopolizing internet search. This one, the third, found Google guilty of a series of dirty tricks to monopolize two advertising technology markets: publisher ad servers, and advertising exchanges. That was in the liability phase, and what we’re waiting for now is the conclusion of the remedy phase of the trial, when we’ll find out what price Google will have to pay for its malfeasance.

I intended to describe for you how a trial on obscure technical issues could possibly be so important, but found I couldn’t. I kept running into unknowably vast questions. This case is about advertising technology, and advertising funds our whole digital world. So it is about who controls the flow of money to businesses. But it is also about the big data and technologies that enable advertising to target you so well, so privacy and autonomy, efficiency and manipulation, democracy and political power are all implicated. Then there’s artificial intelligence; Google’s monopoly on the technologies in this case gives it a big head start in monopolizing AI in coming years. And the rule of law: are the biggest corporations too powerful for law to constrain? This case, perhaps more than any other of our time, will guide the cases against corporate crime lined up behind it. More big issues start crowding in, and I can’t describe it all. So, I’m settling for the most general of summaries, and leaving it at that: the Google ad tech trial lies at the intersection of most of the forces shaping our society’s present and future. That’ll have to do because I’m moving on to the nuts and bolts.

The main trial—the liability phase—took place in the fall of 2024, at which the court asked, Did Google break the law? Judge Brinkema issued her ruling in April of 2025, answering Yes. Then the remedy phase, which I covered last fall, asked, How do we fix it? We are expecting the judge’s decision to come out in the next few months. The big unknown is whether she will break Google up. That is, will she force Google to sell off (“divest”) certain divisions.

You may have noticed—maybe with gratitude—all the free stuff we get from Google: Gmail, Google search, YouTube. Google pays for all that with advertising revenue that it takes away from everyone else with its monopoly power. (Amazon Prime pays for free shipping similarly, by extracting monopoly rents from all the vendors selling on its site, driving up their prices.) You may also have noticed traditional media—the New York Times, The Atlantic, your city’s newspaper—disappearing behind paywalls. For a century and more, journalism was largely paid for by advertising, but that revenue stream has been diverted to the big tech monopolists, and mainstream journalism has switched more and more to a subscription model. All the rest of the “open web,” too, (ordinary websites, as opposed to “walled gardens” like Facebook and Amazon) has been in steady decline for years. None of this is inevitable. As one of the day two witnesses said, these are the effects of a corrupted ad tech market: “They’re starving. They just need food.”

My first article for Big Tech on Trial was a backgrounder. Opening arguments by the Department of Justice (DOJ) and Google, covered in the second, can help you get oriented. Thoughts on the big issues are in the twelfth and last. Very quickly, though, ad tech works like this. In the split second when you click on a webpage, an advertising exchange (or several of them) holds an auction to sell the advertising space on that page (the right to be seen by you). The space is managed by a publisher ad server, which is a company managing lots of websites’ advertising space, and the ad that wins the auction and gets put before your eyes milliseconds later is managed by an advertiser ad network. So, those are the three parts: publisher ad servers, ad exchanges, and advertiser ad networks. Each part is a market, because multiple companies are competing to manage any given site’s space, or place any given ad, or be the exchange through which that space and that ad connect. Google monopolizes all three of these markets, but was only found liable for illegal behavior to gain or maintain its monopoly in two of them, the publisher ad server and ad exchange markets.

Google’s publisher ad server is DFP (formerly Double-Click for Publishers, a company Google acquired on its way to monopolizing this market), and DFP controls a massive 91 percent of publisher (i.e. website) advertising space. AdX is Google’s ad exchange. AdWords is Google’s advertiser ad network. All together, Google places eight million ads per second across the internet, eight million little contracts between advertisers and publishers negotiated per second. It’s a big enterprise.

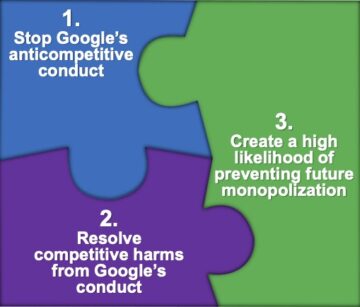

The court’s main goal is to return competition to the illegally monopolized markets (which generally requires ending the monopoly, preventing its reestablishment, etc.). To that end, the two sides each present remedy proposals to the court. Their proposals are very far apart right now, which is one reason nobody expects this case to be settled out of court. (The other big reason is that a settlement would leave this guilty verdict unappealable—set in stone—and private lawsuits by companies that Google’s actions damaged are already being filed citing this case’s verdict, with many more to come.) The more subtextual reason the remedy proposals are so far apart is that, despite losing three out of three cases, Google seems pretty resistant to admitting it did anything wrong. Through two weeks of testimony, Google seemed to question the very authority of antitrust law or the government’s right to end monopolies, restore competition, or require much of anything of the company. As a philosopher, I couldn’t help but think of Socrates’s trial for corrupting the youth of Athens. After being found guilty, Socrates’s remedy proposal to the court was that his punishment should be free meals for life at state expense. Not his finest hour. He probably goaded the court into issuing a death sentence. It is unlikely that Judge Brinkema will order Google to die by drinking hemlock, but mistrust of Google permeated the trial, and Google didn’t try any harder than Socrates did to ingratiate itself to anyone.

The DOJ, in its remedy proposal, asked the court to require Google to sell off its ad exchange, AdX, and to make the Final Auction Logic of its publisher ad server, DFP, open-source. Again very briefly, the publisher makes the final decision on which ad to post on its webpage, which means really its ad server decides, and Google’s DFP is ad server to 91 percent of ads (technically, of “open-web display ads”). Witnesses called DFP’s decision-making a “black box” where no one outside could see how a winning ad was chosen or verify that it was the highest bid, and they accused Google of changing bids and manipulating auctions, and also of hoarding data about the process that both publishers and advertisers needed to make good business decisions. All of which turned out to be true. If it seems odd that the businesses buying and selling ads can’t find out what they bought and sold and paid for it, remember we’re talking about eight million ads per second. There isn’t any way to know what happened except to know what the software makes happen. That transparency is what making DFP’s software open-source would enable.

With the software proprietary, Google’s competitors and customers looked for workarounds. There’s an interesting story I won’t go into of how everyone else in the industry banded together to create “header bidding” through Prebid.org (a public-interest organization whose president testified on day five), which is a way of embedding code in webpage headers to enable everyone else to hold their own millisecond auction before Google does and to submit to AdX only the winner of that auction so they can track what’s going on…. Whew! I find it kind of hilarious how much tactical maneuvering can happen in cyberspace between a mouse click and the page appearing. Anyway, to stop the shenanigans and empower Google’s competitors, the DOJ proposes putting DFP’s software (at least the final part) in the public domain, likely administered by Prebid, and forcing divestiture of AdX. Google responds that such structural remedies are unthinkably heavy-handed, outrageous government overreach, and unprecedented in human history; it assures the court that behavioral remedies—rules about what Google must do and what data it must share—will suffice to solve all complaints against it. This dispute over structural remedies was the trial’s continual focus.

A lot of that fight took the form of debate over the question, Are these structural remedies technically feasible? I won’t go far into that question because, in my opinion, DOJ definitively won the debate. They did it by focusing not on the specifics of how to migrate Google’s admittedly-huge systems (though there were lots of specifics, too), but on industry best practices, as described in Google’s own training manual for its engineers. Well-written code is easy to update, resilient to hardware breakdowns, migratable to new buildings or owners, and so on. And Google’s source code is, as one witness put it, “beautiful.” In this way, DOJ was able to use Google’s own reputation for technical excellence to show the technical feasibility of divesting it of AdX and DFP.

The technical feasibility question was inadvertently put further to rest late in the trial (day ten) by Google’s own witness, computer scientist Jason Nieh of Columbia. Nieh accused the DOJ of not sharing his assumptions that an AdX moved to a new owner would still be as good as the present AdX, and that the move would not disrupt customers. However, this claim by Nieh implied that feasibility was not really the issue: it is indisputably feasible to move something or other, so the real question is whether that something would be as good as AdX. Under cross-examination, Nieh admitted that Google’s counsel had also instructed him to assume that the court would not require Google to surrender any proprietary technology. This led Judge Brinkema to ask Nieh directly if an AdX divestiture would be more feasible (and produce a more equivalent product), if she included the proprietary parts of AdX. (Proprietary technology was shown on diagrams as blank red boxes and could only be referred to obliquely, which produced one of the trial’s charming moments—and an alarming moment for Google—when Judge Brinkema asked, “If all those red boxes go with the divestiture, would that make a difference?”)

With the technical issue settled (as I believe it is), the remaining question is whether divestiture is necessary, whether only structural remedies can restore competition to the markets. And that brings us, finally, to the issue of trust. On day three, in a significant interruption from the bench, Judge Brinkema chided DOJ for the presumption that had permeated their witnesses’ testimony that Google will cheat if it can. She was hinting at a technical legal question of who counts as a “recidivist” (repeat offender), which lead DOJ attorney Julia Tarver Wood had called Google in her opening statement. But behind that was a question of justice about what the court owes the defendant. And behind that is a question of pragmatics. The judge went straight to that fundamental pragmatic issue, saying that lack of trust is what holds up agreements. The hint I take is that her ability to craft a remedy that will rekindle trust in the market, a remedy that will hold up—over time, in the appeals court, in the future ad tech markets, in the political rough-and-tumble—will depend on that remedy being widely recognized as necessary, appropriate, fair and effective.

The witness that Judge Brinkema interrupted to make these points was DOJ’s main economics expert, Robin Lee of Harvard. Lee had been saying that, as an economic matter, it is most effective to prevent the ability to commit a harm. DOJ’s structural remedies would deprive Google of the ability to re-monopolize ad tech, while behavioral remedies alone would not. The judge was pushing back, saying the prosecution’s convenience is not the measure of a remedy’s pragmatic robustness (which is why “Throw away the key” is not carved on courthouse porticos). So the trust issue was joined on day three (there was a similar interaction with Stephanie Layser on day ten), but it sat uncomfortably tacit throughout the trial, never becoming very clear.

I would argue that the trust issue was misleadingly framed—for which Judge Brinkema herself was partially to blame—as an either/or choice that maps straight onto the choice between behavioral and structural remedies. If Google can be trusted, this framing implies (trusted, that is, under court supervision and threat of additional lawsuits, which the judge called at one point “the two elephants in the room”), then behavioral remedies will suffice. Structural remedies are necessary only if Google cannot be trusted (and, by implication, court supervision cannot be, either). Here is a paraphrase from a Google-aligned group (Chamber of Progress) of that interaction between the judge and Prof. Lee: “Couldn’t this all be precluded by strong, specific language in a ruling, rather than a divestiture? The witness was forced to concede that, yes, it could.” In this form, the trust issue came all the way through to the closing arguments, where Karen Dunn, Google’s lead attorney, presented mistrust of Google as the sole rationale for structural remedies.

I want to make a different argument: that an adversarial legal system—which is symbiotic with a competitive market system, both pragmatically and philosophically—requires that courts take a very skeptical view of the power of “strong, specific language in a ruling” to constrain behavior. This is my elaboration of a powerful point made by Matthew Huppert in DOJ’s closing argument.

Closing arguments were six weeks later, November 21, and were insightfully recounted for BTOT by Laurel. I was there and will try to describe a difference between the two sides that I think cuts quite deep. Dunn argued that behavioral remedies accomplish the same thing as structural ones, if Google follows them. Therefore, unless Google is untrustworthy, structural remedies are unnecessary. Something’s not right. Something is tautological or circular here. Of course they accomplish the same, if Google acts the same either way! But then, telling Google “Go, and sin no more” would also accomplish the same, if Google acts the same. We want a court monitor and a ruling with “strong, specific language” because we want to know how we can expect Google to act, want to know what “acts the same” amounts to. But does such a ruling give us all the same knowledge that a structural remedy gives us?

A striking part of DOJ’s closing argument was a series of hypotheticals Huppert presented of unknowns that we—meaning the court’s monitor, Google, Google’s competitors and customers—might plausibly face in the future. Behavioral remedies inescapably contain complex, vague, and disputable terms: “intentional,” “qualifying,” “technical reality,” “effective,” “better.” As US v Google Ads paraphrased one example (in their excellent summary), “If Google causes AdX to send bids 400 milliseconds slower, was it intentional? Was it a ‘technical reality?’ We’d be back in Court to figure that out—each and every time.” Yes, mistrust of Google was mixed into DOJ’s presentation here, and Google’s long history of bending rules and “testing every boundary” was appropriately mentioned. But Huppert was also making the more general point, which is what I want to emphasize: law, business, and life itself are all full of ill-defined concepts requiring judgment and flexibility to apply. But this fact of life is one that the peculiarly pragmatic discipline of law has always been peculiarly well equipped to handle.

It is a principle of jurisprudence that the full meaning of a statute is worked out over time, in case after case. This principle was famously expressed in 1897 by Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.: “The prophecies of what the courts will do in fact, and nothing more pretentious, are what I mean by the law.” Strong, specific language in a ruling is helpful, sure, but it is not enough. Even with the best of intentions, people will interpret rules differently and predict the future actions of judges differently. There will be nothing to do but argue it out when it happens.

Google may or may not be trustworthy. But that is not the real trust issue. It is words that cannot be trusted. And for all its verbal pomp, the law knows this. This is why non-verbal structural remedies are “clean” and “certain” and all those other words DOJ found Supreme Court precedents using to describe them. Skepticism of behavioral remedies does not presume that Google will cheat but rather that the application of the court’s ruling will inevitably be debatable. Conflicts over Google’s future behavior will arise, not because Google is evil but because that is the nature of the universe: people will disagree, about the meanings of rulings and about the right thing to do. Structural remedies change the context of those future disagreements. When disputes arise over words—including those of Judge Brinkema’s forthcoming ruling—all parties can trust that the power and incentives will not be there to recreate monopolies, undermine competition, and thwart the hard work of the court.